Conjunctivitis

Conjunctivitis is inflammation of the transparent surface layer that covers the white of the eye (the conjunctiva).

About conjunctivitis

Types of conjunctivitis

Symptoms of conjunctivitis

Causes of conjunctivitis

Diagnosis of conjunctivitis

Treatment of conjunctivits

About conjunctivitis

There are two main types of conjunctivitis, based on what has caused the condition – an infection or an allergy.

Conjunctivitis can also be caused if an irritant such as a chemical, or a foreign body such as a piece of grit, gets into your eye.

Types of conjunctivitis

Infective conjunctivitis

Infective conjunctivitis is caused by infection of your eye with bacteria or a virus.

Sometimes babies develop conjunctivitis in the first few weeks after they are born. This can happen if an infection is passed from the mother's cervix (neck of her womb) or vagina during delivery, or if the baby has a reaction to a treatment applied to his or her eye. Contact your GP if your newborn baby has signs of an eye infection.

Allergic conjunctivitis

Allergic conjunctivitis can be caused by an allergy, such as an allergy to pollen (hay fever), house dust mites or cosmetics.

There are four types of allergic conjunctivitis:

- seasonal allergic conjunctivitis – this affects both of your eyes and people often get it at the same time as hay fever

- perennial allergic conjunctivitis – people with this type of allergic conjunctivitis have symptoms every day throughout the year in both eyes, often on waking each morning

- contact dermatoconjunctivitis – this type of conjunctivitis can irritate your eyelids and it occurs most often in people who use eye drops

- giant papillary conjunctivitis – this is common in people who use soft contact lenses, although it can also occur in people using hard contact lenses and after eye surgery

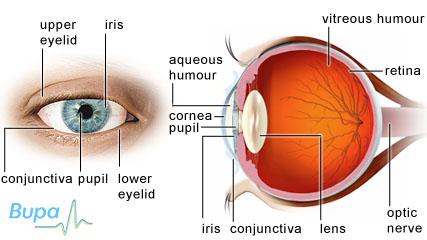

[Insert illustration with label: The different parts of the eye]

Symptoms of conjunctivitis

Conjunctivitis can affect one or both of your eyes and cause symptoms including:

- soreness, often described as a gritty or burning feeling

- redness of the whites of your eye

- blurred vision

- watering or discharge from your eye

- a slight sensitivity to light

Your symptoms will depend on which type of conjunctivitis you have.

If you have allergic conjunctivitis, you may also have:

- swollen eyelids

- itchy and watery eyes

- other hay fever symptoms, including sneezing, a runny, itchy nose and itchiness at the back of your throat

- a rash on your eyelids (if your conjunctivitis is caused by an allergic reaction to a medical or cosmetic product)

If you have infective conjunctivitis, you may also have:

- yellow pus-like discharge from your eyes, which might make your eyelids stick together after you sleep (if you have a bacterial infection)

- a watery discharge that can be crusty in the morning but isn’t pus-like (if you have a viral infection)

- cold-like symptoms, such as a fever and sore throat

- swollen lymph nodes in front of your ears (lymph nodes are glands throughout your body that are part of your immune system)

When to see a doctor

See your GP straight away if your eyes are very red, or if you have red eyes as well as:

- severe pain in your eyes

- sensitivity to light

- difficulty seeing

You should also contact your GP if you have had symptoms of conjunctivitis for more than a few days.

Causes of conjunctivitis

Infective conjunctivitis

Viruses are thought to be a more common cause of conjunctivitis than bacteria. The type of virus that usually causes the condition is called an adenovirus. This virus can also cause the common cold, so you may develop conjunctivitis at the same time as having a cold.

Common causes of bacterial conjunctivitis include the bacteria Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae. You can catch infective conjunctivitis from being in close contact with another person who has it. It’s important to wash your hands after coming into contact with someone who has the condition.

Infective conjunctivitis is most common in children and older people.

Allergic conjunctivitis

You might develop allergic conjunctivitis if you're allergic to plant pollens that are released into the air at around the same time each year. This is called seasonal allergic conjunctivitis or hay fever conjunctivitis.

Perennial (all year round) allergic conjunctivitis can be caused by house dust mites or animal fur.

Eye drops, cosmetics, and other chemicals can also cause allergic conjunctivitis – eye drops are the most common cause.

You can get a form of allergic conjunctivitis called giant papillary conjunctivitis if you use contact lenses, or after eye surgery.

Irritants

Foreign bodies, such as an eyelash or a piece of grit, or chemicals, such as chlorine, getting in your eye can cause conjunctivitis. Conjunctivitis caused by a foreign body may only affect one of your eyes.

Diagnosis of conjunctivitis

Your GP will ask about your symptoms and examine you. He or she may also ask you about your medical history. You may be asked to read a chart to check your vision.

Your GP may use a special dye and a blue light to look at the surface of your eye. This is called a fluorescein examination. If your GP thinks that you have infective conjunctivitis, he or she may take a swab of your eye to identify the cause. The swab will be sent to a laboratory for testing.

Your GP may refer you to an ophthalmologist (a doctor who specialises in eye heath).

Treatment of conjunctivitis

Self-help

If you normally use contact lenses, don't wear them until the conjunctivitis has cleared up. It's also important that you don't rub your eyes because this can make inflammation worse.

If you have allergic conjunctivitis, try to keep away from whatever is causing the allergy. For example if you’re allergic to a cosmetic, don’t use it again and try an alternative product (wait until your symptoms have gone before you try the new product). It may be more difficult if you’re allergic to pollen, but keeping windows and doors closed on days when the pollen count is very high may help to reduce your symptoms. A cool compress (a facecloth soaked in cold water) may help to soothe your eyes.

Infective conjunctivitis usually settles without treatment within one to three weeks but this can vary between individuals. It may help if you clean your eyes and remove any secretions from your eyelids and lashes with cotton wool soaked in water.

Infective conjunctivitis is contagious. So it’s important to wash your hands regularly, particularly after touching your eyes. It’s best not to share pillows and towels. Don’t go swimming until your conjunctivitis has cleared up. You don't necessarily need to take time off work when you have conjunctivitis, and if your children develop it they can still go to school – unless there are many people affected in an ‘outbreak’ of conjuntivitis.

Medicines

If you have bacterial conjunctivitis, your GP may prescribe antibiotic eye drops or ointment. These are also available over-the-counter at a pharmacy.

Viral conjunctivitis will clear up on its own without the need for medicines.

If you have allergic conjunctivitis, antihistamine medicines may help. These are available over-the-counter from a pharmacy or your doctor can prescribe them. They are available in the form of eye drops or tablets.

Your doctor may also prescribe eye drops called mast cell stabilizers. These are also available over-the-counter. These are more effective at controlling your symptoms over a longer period of time (rather than antihistamines that will give rapid relief). It may take several weeks before you feel that they are having an effect, but you can take an antihistamine at the same time so that your symptoms can be controlled while you’re waiting.

Always read the patient information that comes with your medicine and if you have any questions, ask your pharmacist or doctor for advice.

This section contains answers to common questions about this topic. Questions have been suggested by health professionals, website feedback and requests via email. This section will expand over time. See our answers to common questions about conjunctivitis, including:

Is there anything I can do to help ease my symptoms when I have conjunctivitis?

What's the difference between a sticky eye and conjunctivitis in babies?

Why are contact lens wearers more prone to getting conjunctivitis?

Is there anything I can do to help ease my symptoms when I have conjunctivitis?

Yes, there are several self-help measures that you can take to reduce the symptoms of conjunctivitis.

Explanation

If you wear contact lenses, it’s important to remove them because they will irritate your eyes. Try not to wear them again until your symptoms have gone, or until at least 24 hours after you have finished treatment.

To help soothe your eyes, place a cold compress (a facecloth soaked in cold water) over your affected eye(s).

There are also steps you can take to stop your symptoms getting any worse or spreading.

- Clean away any crusting or discharge from your eyelids and eyelashes using cotton wool balls soaked in water.

- Don't rub your eyes.

- Wash your hands regularly, especially after you've touched your eyes.

- Don't share towels or pillows.

If your symptoms are caused by an allergy (e.g. to pollen or house dust mites), try to keep away from the allergen as much as possible. When the pollen count is high, you can do this by:

- keeping windows in buildings and cars closed

- wearing wraparound sunglasses

- taking a shower and washing your hair as soon as you get in

- not drying your washing outside

If you’re allergic to house dust mites it may help to:

- fit a mattress with a dust mite impermeable cover

- use synthetic pillows and an acrylic duvet

- wash all your bedding at least once a week

If you have any questions or concerns about self-help measures for conjunctivitis, speak to your GP.

What's the difference between a sticky eye and conjunctivitis in babies?

A sticky eye is very common in young babies and often resolves itself without any treatment within a year. However, conjunctivitis in newborn babies (in their first few weeks of life) can be a sign of a more serious infection. If you think your baby has conjunctivitis, it's important to contact your GP as soon as possible.

Explanation

In all babies, their tear drainage system isn't properly developed until they are born. The bottom of their nasolacrimal duct, the duct that carries tears into their nose, is usually not fully open. In most cases the opening quickly develops, resolving the problem. However, for up to one in five babies, in their first month the duct remains closed at the bottom causing a watery, sticky eye. This is commonly known as ‘sticky eye’. The medical term is ‘congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction’.

The first symptoms you may notice are that your baby's eyes are watering for no reason (i.e. he or she isn’t emotional or upset). This may be the odd trickle down their cheek or tears may roll down their face. There may also be some pus and crusting around his or her eyes.

The symptoms of conjunctivitis can include watering eyes, just like with a sticky eye, so it can sometimes be difficult to tell the difference between the two conditions. However, with conjunctivitis your baby may also have:

- soreness and discomfort

- itchiness - you may notice that your baby is rubbing his or her eyes more than usual

- redness of the whites of his or her eye

- slight sensitivity to light

Your baby may be distressed by these symptoms, more so than if they simply have a sticky eye.

It's important to speak to your GP if you think your baby has conjunctivitis, as it can be the result of an infection passed to your child at birth. The two most serious infections are chlamydia, which can cause your baby to develop pneumonia, and gonorrhoea, which can develop into a severe eye infection.

Why are contact lens wearers more prone to getting conjunctivitis?

Conjunctivitis, specifically giant papillary conjunctivitis, is a common condition in people who wear contact lenses. It's often triggered by chemicals and preservatives in contact lens solutions or the lens themselves, which cause your eyes to become irritated and itchy.

Explanation

You can get giant papillary conjunctivitis if your body reacts to an allergen in your tears or on your contact lenses. An allergen is a substance that can cause an allergic reaction. Your body's immune system mistakes the allergen for a harmful invader causing a reaction. Allergens aren't usually harmful and most people aren't sensitive to them. For contact lens wearers, the allergen is usually found in the chemicals and preservatives in contact lens care solutions, eye drops or the lenses themselves.

The allergen causes parts of your conjunctiva (the transparent surface layer that covers the white of your eye) to swell and produce too much mucus. This makes your eye(s) feel itchy and irritated, and can make wearing contact lenses uncomfortable. Some people find that their lenses move around every time they blink, making their symptoms even worse.

You will need to stop wearing your contact lenses if you have giant papillary conjunctivitis. Often this will immediately stop the overproduction of mucus in your eyes, but the redness and soreness may remain. It's important to see your GP or optometrist so that he or she can examine your eyes and exclude other eye conditions. An optometrist is a registered health professional who examines eyes, tests sight and dispenses glasses and contact lenses.

Your optometrist may advise you to wear your lenses for shorter periods of time or less frequently. Also you may need to change the products you use to care for your lenses. Sometimes you may need to switch to different lenses altogether.

Occasionally, you may need to be referred to an ophthalmologist for further diagnosis and treatment. An ophthalmologist is a doctor who specialises in eye heath, including eye surgery.

Often no treatment is necessary, as symptoms start to reduce as soon as you remove your contact lenses. To help soothe your eyes, place a cold compress (a facecloth soaked in cold water) over your affected eye(s). Also make sure you don't rub your eyes no matter how itchy they are. Occasionally, if symptoms are particularly bad, your doctor may prescribe an allergy medicine.

If you have any questions or concerns about giant papillary conjunctivitis, talk to your doctor or optometrist.

Further information

-

The Royal College of Ophthalmologists

020 7935 0702

www.rcophth.ac.uk

Sources

- Conjunctivitis - infective. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. www.cks.nhs.uk, accessed 30 September 2009

- Conjunctivitis. Medlineplus. www.nlm.nih.gov, accessed 30 September 2009

- Bacterial conjunctivitis. Clinical Evidence. www.clinicalevidence.bmj.com, accessed 30 September 2009

- Conjunctivitis – allergic. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. www.cks.nhs.uk, accessed September 30 2009

- Conjunctivitis. Merck manuals online medical library. www.merck.com, 30 September 2009

- Factsheet on conjunctivitis. Health Protection Agency. www.hpa.org.uk, accessed 30 September 2009

- Young JDH, MacEwen CJ. Fortnightly review: Managing congenital lacrimal obstruction in general practice. BMJ 1997; 315(7103):293-96

- Clinical management guidelines: CL-associated papillary conjunctivitis (CLPC), giant papillary conjunctivitis (GPC). The College of Optometrists. www.college-optometrists.org, accessed 4 October 2009

- Conjunctivitis, giant papillary. Emedicine. www.emedicine.medscape.com, accessed 4 October 2009

- Conjunctivitis. Health Protection Agency North West. www.hpa.org.uk, accessed 28 October 2009

- Beers MH, Fletcher AJ, Porter R, et al., The Merck manual of medical information. New York: Pocket Books, 2003:1296-97

- Conjunctivitis. American Optometric Association. www.aoa.org, accessed 28 October

Related topics

- Chlamydia

- Gonorrhoea

- Hay fever

- Antibiotics

- Common cold

Publication date: January 2010.