Heart valve surgery

[Published by Bupa's health information team, April 2010.]

This factsheet is for people who are planning to have heart valve surgery, or who would like information about it.

Heart valve surgery treats heart valve disease. It involves repairing or replacing one or more heart valves that may be diseased or damaged.

Your care will be adapted to meet your individual needs and may differ from what is described here. So it’s important that you follow your surgeon’s advice.

How heart valve replacement surgery is carried out

About heart valve surgery

Getting advice about heart valve surgery

Preparing for heart valve surgery

What happens during heart valve surgery

What to expect afterwards

Recovering from heart valve surgery

What are the risks?

How heart valve replacement surgery is carried out

The information on the video provided does not constitute advice on diagnosis or the treatment for heart disease and such advice should always be sought from a doctor or another suitably qualified health professional.

About heart valve surgery

Heart valve disease causes your heart to pump less efficiently. Blood doesn’t flow through your heart properly, which puts extra strain on your heart. This causes symptoms such as breathlessness, chest pain, tiredness and swollen ankles.

Heart valve surgery treats leaking or narrowed valves to eliminate or improve your symptoms. It may prevent permanent damage to your heart.

Getting advice about heart valve surgery

If you have mild heart valve disease, medicines (eg diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, digoxin) can relieve symptoms.

You can discuss alternatives to heart valve surgery with your GP.

Preparing for heart valve surgery

Your surgeon will explain how to prepare for your operation. For example, if you smoke you will be asked to stop, as smoking increases your risk of getting a chest or wound infection, which can slow your recovery.

You will generally stay in hospital for up to ten to 12 days. This operation is usually done under general anaesthesia, so you will be asleep during the operation.

In hospital, your nurse may check your heart rate and blood pressure, and test your urine. You may have a breathing test to check your lung function. You will have an X-ray, electrocardiogram (ECG) or echocardiogram before the operation.

Your surgeon will discuss with you what will happen before, during and after your procedure, and any pain you might have. This is your opportunity to understand what will happen, and you can help yourself by preparing questions to ask about the risks, benefits and any alternatives to the procedure. This will help you to be informed, so you can give your consent for the procedure to go ahead, which you may be asked to do by signing a consent form.

You will be asked to follow fasting instructions. Typically, you must not eat or drink for about six hours before a general anaesthetic. However, it’s important to follow your anaesthetist’s advice.

You may be asked to wear compression stockings to maintain your circulation. You may also need to have an injection of an anti-clotting medicine called heparin.

What happens during heart valve surgery

Heart valve surgery can take up to three hours.

The surgeon will make a cut, about 25cm (10 inches) long, down the middle of your breastbone (sternum) to reach your heart.

There are different ways to mend the valve.

• If your valve isn’t seriously damaged, it may be possible to repair it.

• A narrowed valve may be widened.

• An artificial ring may be added to strengthen the valve.

• If your valve is seriously damaged, it may be replaced.

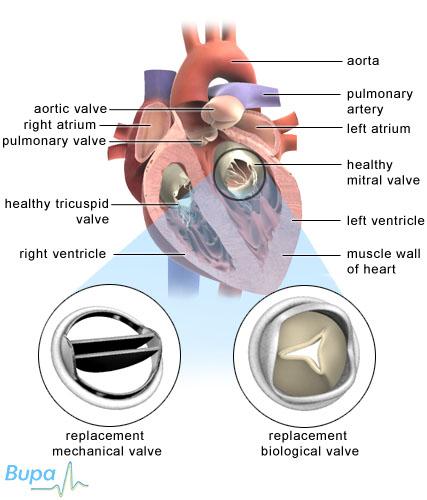

There are two types of prosthetic (artificial) valve.

• Mechanical valves are made of carbon fibre. Sometimes, they make a clicking sound but most people quickly get used to this. These valves can last for a lifetime.

• Biological valves are made from human or animal tissue. Biological valves wear out faster than mechanical valves, so the surgery may need to be repeated every eight to 10 years.

Your surgeon will advise you about the type of heart valve surgery that you’re having.

Your sternum will be rejoined using wires and the skin on your chest will be closed with dissolvable stitches.

Keyhole surgery

Your surgeon may do the operation using keyhole (minimally invasive) surgery. Instruments and a camera are passed through smaller cuts and the surgeon uses the camera as a guide during the operation.

There is also a technique called percutaneous valve replacement. A tube is passed through an artery or in your groin, or a vein in your leg to replace a heart valve.

Keyhole surgery isn’t suitable for everybody. Your surgeon will advise you on what is best for you.

What to expect afterwards

You will be taken to the intensive care unit (ICU) of the hospital and will be closely monitored for about 24 hours.

When you wake up, you will be connected to machines that record the activity of your heart, lungs and other body systems. These might include a ventilator machine to help you breathe.

You may need pain relief to help with any discomfort as the anaesthetic wears off.

A catheter may be placed to drain urine from your bladder into a bag. You may also have tubes running from the wound to drain any fluid into a bag. These are usually removed after a day or two.

You will be encouraged to get out of bed and move around because this helps prevent chest infections and blood clots in your legs. A physiotherapist will visit you regularly from the second day after the operation to help you do exercises to aid your recovery.

After about a week, you will be able to go home. You need to arrange for someone to drive you home and try to have a friend or relative stay with you for the first 24 hours. Tell your GP when you’re discharged from hospital, so he or she is aware of your care needs.

Your nurse will give you advice about caring for your healing wounds before you go home. You may be given a date for a follow-up appointment.

The wires holding your sternum together are permanent. Dissolvable stitches closing the skin wound will disappear in seven to 10 days.

If you're in any doubt about driving, contact your motor insurer so that you're aware of their recommendations, and always follow your surgeon’s advice. If you drive a lorry or a bus, you need to notify the DVLA about your operation.

Recovering from heart valve surgery

If you need pain relief, you can take over-the-counter painkillers such as paracetamol or ibuprofen. Don’t take ibuprofen if you are taking warfarin.

Always follow the instructions in the patient information leaflet that comes with the medicine and if you have any questions, ask your pharmacist for advice.

A full recovery can take two to three months. Your surgeon will give you advice about how soon you can return to work.

Go to your GP if you have:

• new or severe heart palpitations

• shortness of breath

• sweating – more than normal

• a high temperature

• eyesight problems

• dizziness

• swelling or a discharge oozing from your wound

What are the risks?

Heart valve surgery is commonly performed and generally safe. However, in order to make an informed decision and give your consent, you need to be aware of the possible side-effects and the risk of complications of this procedure.

Side-effects

These are the unwanted, but mostly mild and temporary effects of a successful treatment – for example, feeling sick as a result of the general anaesthetic.

After heart valve surgery, it’s normal to feel some discomfort. You may have some fluid, which may be blood-strained, coming from the cut in your chest. A dressing may be placed over this area.

You are likely to have permanent scars on your chest. The scars will be red at first but should fade over time.

Complications

This is when problems occur during or after the operation. Most people are not affected. The possible complications of any operation include an unexpected reaction to the anaesthetic, infection, excessive bleeding or developing a blood clot, usually in a vein in the leg (DVT).

Specific complications of heart valve surgery are rare but can include:

• a heart attack

• a stroke

• there is a risk of death but this is rare – however, it’s important to consider that having no treatment or having an alternative treatment may have a higher risk

• a blood clot may form which could block a replacement valve – you may need to take blood thinning medicines (anticoagulants), such as warfarin, for the rest of your life to prevent this

• heart block – when the valve is replaced, the conducting system of the heart may become damaged and you may need a pacemaker fitted

If you have keyhole surgery, there’s a chance your surgeon may need to convert your keyhole procedure to open surgery. This means making a bigger cut in your chest. This is only done if it’s not possible to complete the operation safely using the keyhole technique.

The exact risks are specific to you and differ for every person, so we have not included statistics here. Ask your surgeon to explain how these risks apply to you.

Will I need to continue with any treatments after I have surgery?

Yes usually, but this depends on the type of surgery you have and your health before the operation. You may need to take medicines such as antibiotics and anticoagulants after your surgery. You may also need to continue taking other medicines for your heart valve disease such as ACE inhibitors (eg ramipril) or diuretics (eg furosemide).

Explanation

After your valve replacement surgery you may need to take anticoagulants such as warfarin. These medicines help stop blood clots from forming. The length of time you will need to take these for depends on the type of replacement valve that you had.

If you had a biological valve, then you will only need to take anticoagulants for a few weeks. After this, you will need to take aspirin to reduce the risk of clots forming around your replacement valve.

If you had a mechanical valve, then you will need to take anticoagulants for the rest of your life. This is because these valves are made from artificial material and so clots are more likely to form around them.

You may also need to take anticoagulants for a few weeks if you have a specific form of arrhythmia (a disturbance of the normal electrical rhythm of your heart) called atrial fibrillation. You may be prescribed anticoagulants if you have had, or are at increased of, a stroke.

While you are taking anticoagulants, you will need to have regular blood tests to ensure that you are on the correct dose. It’s very important that you are on the correct dose of anticoagulant as too much of these medicines can lead to bleeding.

If you are at risk of infection, your doctor or surgeon may give you antibiotics before and after your operation to prevent your valve from becoming infected. If your valve becomes infected, the infection can spread to the lining of your heart (endocarditis). Endocarditis is a serious condition that can lead to damage to the heart valves.

To help prevent infection, you should practice good dental hygiene and have regular dental checkups. This stops the bacteria in your mouth from entering your bloodstream.

Your GP will advise you about taking anticoagulants after your operation. For information about preventing endocarditis, consult your GP.

Further information

British Heart Foundation

0300 330 3311

www.bhf.org.uk

Sources

• Heart valve disease. British Heart Foundation. August 2009. www.bhf.org.uk

• Having heart surgery. British Heart Foundation. January 2005. www.bhf.org.uk

• Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary. 56th ed. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 2009:100

• Personal communication, Dr Tim Cripps, Consultant cardiologist, Bristol Royal Infirmary, 10 February 2010

• Simon C Everitt H Kendrick T. Oxford handbook of general practice. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2007:354–55

• Vahanian A, Baumgartner H, Bax J, et al. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2007; 28:230–68

H2 Is there anything I can do to speed up my recovery?

Yes, there are some things you can do. You can take measures such as joining a cardiac rehabilitation programme to help your recovery. It will take up to three months to recover completely, so you will need to take things easy until then.

Explanation

It can take up to three months to recover fully from heart surgery and during this time you will need to build yourself back up to normal.

For the first six weeks after your operation, you should limit the amount of alcohol you drink. One unit per day is a sensible limit. The effects of alcohol can be greater if you are taking certain medicines, and alcohol can interfere with certain medicines. Always ask your GP for advice and read the patient information leaflet that comes with your medicine.

You may be recommended to take part in a cardiac rehabilitation programme. This will cover exercise, relaxation and lifestyle changes that can help you recover. For example you may get advice on:

• diet and healthy eating

• how to recognise stress

• how to stop smoking

• medicines

• returning to work

For advice on cardiac rehabilitation programmes, ask your GP or contact the British Heart Foundation.

Further information

British Heart Foundation

0300 330 3311

www.bhf.org.uk

Sources

• Having heart surgery. British Heart Foundation. January 2005. www.bhf.org.uk

When can I start exercising after surgery and what is suitable for me?

Your physiotherapist will help you to start moving about two days after your surgery. Once you get home, you should build your activity levels up slowly until you are back to your usual level of activity.

Explanation

It’s important to keep active when you get home after your surgery. Try to do the same amount of exercise at home as you did with the physiotherapist at the hospital.

It’s important to rest properly too. When you sit down, make sure that you have your feet raised, on a stool for example. Your legs should be supported, so don’t sit too far away from the stool. You should set aside specific times to rest and make sure that you stick to them.

After the first few days, you can start to increase the amount of exercise you do. Gentle walking is a good way to do this. Ask your physiotherapist for information about suitable exercises and how to build up your levels of activity.

The best kind of exercise for your heart is aerobic activity. Aerobic activity can be any repetitive exercise that involves the large muscle groups of your legs, shoulders or arms.

It’s very important to increase your levels of physical activity gradually. You shouldn’t do any strenuous or vigorous activity such as weightlifting as this can put a strain on your heart.

With any exercise, you may want to involve your partner, family or friends to make it more fun.

You should stop exercising immediately if you feel:

• pain

• dizzy or light-headed

• sick

• unwell

• very tired

If you develop any of these symptoms and they don’t go away after a few minutes, you should see your GP.

Further information

British Heart Foundation

0300 330 3311

www.bhf.org.uk

Sources

• Having heart surgery. British Heart Foundation. January 2005. www.bhf.org.uk

• Physical activity and your heart. British Heart Foundation. October 2009. www.bhf.org.uk

My doctor says that I have a mitral valve prolapse. What is this and do I need treatment?

About five in every 100 people have a mitral valve that is slightly mis-shapen and leaks. You won’t usually need treatment unless you have symptoms such as palpitations or chest pain.

Explanation

A mitral valve prolapse can be a cause of a heart murmur (a noise from your heart caused by irregular blood flow) but doesn’t usually cause serious problems. If you have a heart murmur, your GP will refer you to a cardiologist (a doctor specialising in identifying and treating conditions of the heart and blood vessels) to find out exactly what is causing it.

A mitral valve prolapse doesn’t usually have any symptoms but you may have chest pain (angina) or palpitations (an unpleasant awareness of the heartbeat, often described as a thumping in the chest).

You won’t usually need treatment unless it’s causing you problems. Your GP may prescribe you beta-blockers (eg bisoprolol) to help with your chest pain and palpitations.

Further information

British Heart Foundation

0300 330 3311

www.bhf.org.uk

Sources

• Heart valve disease. British Heart Foundation. August 2009. www.bhf.org.uk

• Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary. 56th ed. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 2009:100

• Longmore M, Wilkinson I, Turmezei T, et al. Oxford handbook of clinical medicine. 7th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008

Will I need to make any lifestyle changes after heart valve surgery?

If your heart valve disease was caused by coronary artery disease, which reduced the blood supply to the heart causing the valves, to stop working as they should, then you need to take measures to stop this getting worse.

Explanation

Damage to the heart valves can be caused by coronary artery disease. If this has happened to you, you should change your lifestyle to prevent coronary heart disease from getting worse. You should:

• stop smoking if you smoke

• eat a healthy, balanced diet

• maintain a healthy weight

• stay active

A healthy, balanced diet is part of reducing cholesterol levels and high blood pressure. You should change your diet to a low fat, low salt diet that includes plenty of fruit and vegetables.

If your repaired valve becomes infected, the infection can spread to the lining of your heart (this is known as endocarditis). Endocarditis is a serious condition that can lead to heart failure. After a heart valve repair operation, and for the rest of your life, you will need to take measures to prevent infection.

The most common way for bacteria to get into your blood is from your mouth when you have dental treatment. To help prevent infection you should practice good dental hygiene and have regular dental checkups. This stops the bacteria in your mouth from entering your bloodstream.

For information about preventing endocarditis and about reducing cholesterol levels and high blood pressure, talk to your GP.

Further information

British Heart Foundation

0300 330 3311

www.bhf.org.uk

Sources

• Having heart surgery. British Heart Foundation. January 2005. www.bhf.org.uk

• Longmore M, Wilkinson I, Turmezei T, et al. Oxford handbook of clinical medicine. 7th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008

• Simon C, Everitt H, Kendrick T. Oxford handbook of general practice. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007:354–55

Related topics

• Cardiovascular system

• Diagnosing heart conditions

• Giving up smoking

• Healthy eating

• Healthy weight for adults

• Heart valve disease

• Looking after your heart

[This information was published by Bupa’s health information team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been peer reviewed by Bupa doctors. The content is intended for general information only and does not replace the need for personal advice from a qualified health professional.

Publication date: April 2010]

Further information

British Heart Foundation

0300 330 3311

www.bhf.org.uk

Related topics

• ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers: http://hcd2.bupa.co.uk/fact_sheets/html/ace_inhibitors.html

• Arrhythmia: http://hcd2.bupa.co.uk/fact_sheets/html/arrhythmia.html

• CABG: http://hcd2.bupa.co.uk/fact_sheets/html/con_art_bypass.html

• Cardiovascular system: http://hcd2.bupa.co.uk/fact_sheets/html/the_cardiovascular_system.html

• Caring for surgical wounds: http://hcd2.bupa.co.uk/fact_sheets/html/surgical_wounds.html

• Compression stockings: http://hcd2.bupa.co.uk/fact_sheets/html/compression_stockings.html

• Deep vein thrombosis: http://hcd2.bupa.co.uk/fact_sheets/html/deep_vein_thrombosis.html

• Diagnosing heart conditions: http://hcd2.bupa.co.uk/fact_sheets/html/diagnosing_heart.html

• Diuretics: http://hcd2.bupa.co.uk/fact_sheets/html/diuretics.html

• General anaesthesia: http://hcd2.bupa.co.uk/fact_sheets/html/anaesthesia.html

• Giving up smoking: http://hcd2.bupa.co.uk/fact_sheets/html/stopping_smoking.html

• Healthy eating: http://hcd2.bupa.co.uk/fact_sheets/html/healthy_eating.html

• Healthy weight for adults: http://hcd2.bupa.co.uk/fact_sheets/html/diet_and_weight.html

• Heart valve disease: http://hcd2.bupa.co.uk/fact_sheets/html/heart_valve_disease.html

• Local anaesthesia and sedation: http://hcd2.bupa.co.uk/fact_sheets/html/local_anaesthesia.html

• Looking after your heart: http://hcd2.bupa.co.uk/fact_sheets/html/looking_after_your_heart.html

• Over-the-counter painkillers: http://hcd2.bupa.co.uk/fact_sheets/html/otc.html

Sources

• At a glance guide to the current medical standards of fitness to drive. Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA). www.dvla.gov.uk, accessed 14 January 2010

• Balloon valvuloplasty for aortic valve stenosis in adults and children. The National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), July 2004. www.nice.org.uk

• Balloon dilatation of pulmonary valve stenosis. The National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), June 2004. www.nice.org.uk

• Having heart surgery. British Heart Foundation, January 2005. www.bhf.org.uk

• Heart valve disease. British Heart Foundation, May 2009. www.bhf.org.uk

• Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary. 56th ed. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 2009:100

• Kumar P, Clark M. Clinical medicine. 6th ed. Elsevier, 2005:768

• Percutaneous pulmonary valve implantation for right ventricular outflow tract dysfunction. The National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), November 2007. www.nice.org.uk

• Personal communication, Dr Tim Cripps, Consultant cardiologist, Bristol Royal Infirmary, 10 February 2010

• Simon C, Everitt H, Kendrick T. Oxford handbook of general practice. 2nd ed. Oxford:Oxford University Press, 2007:354-55

• Thoracoscopically assisted mitral valve surgery. The National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), December 2007. www.nice.org.uk

• Tuladhar SM, Punjabai PP. Surgical reconstruction of the mitral valve. Heart 2006; 92:1373–77. doi: 10.1136hrt2005.067421

• Vahanian A, Baumgartner H, Bax J, et al. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2007; 28:230–68.

[This information was published by Bupa’s health information team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been peer reviewed by Bupa doctors. The content is intended for general information only and does not replace the need for personal advice from a qualified health professional.

Publication date: April 2010]