Acute middle ear infection in children

Published by Bupa's Health Information Team, December 2011.

This factsheet is for parents of children with an acute middle ear infection, or for people who would like information about it.

A middle ear infection (otitis media) is an infection that causes inflammation of the middle ear.

About acute middle ear infection

Symptoms of acute middle ear infection

Causes of acute middle ear infection

Diagnosis of acute middle ear infection

Treatment of acute middle ear infection

Prevention of acute middle ear infection

About acute middle ear infection

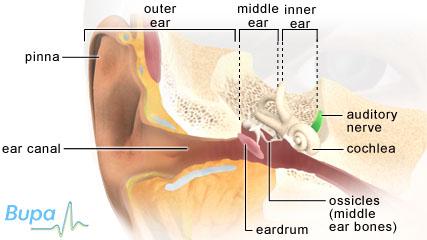

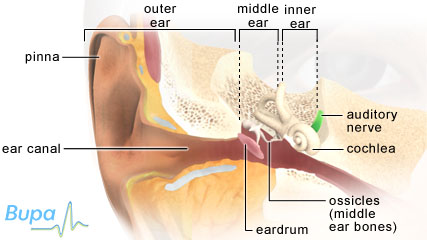

The middle ear

The middle ear is the space behind your eardrum. It contains three tiny bones that move when sounds reach them. These transmit sound waves through your middle ear to your inner ear. Usually, your middle ear is filled with air, but if you have inflammation, the space becomes filled with mucus. The Eustachian tube connects your middle ear with your throat and opens when you swallow. This allows air to pass up and down the tube from your throat to the middle ear and in the opposite direction. This equalises the air pressure inside your ear to the air pressure outside your ear. When it's inflamed, the Eustachian tube doesn't open properly and so mucus stays in the middle ear.

Middle ear infections are most common in children. Adults are affected too, but three-quarters of those diagnosed are children under the age of 10.

An acute middle ear infection comes on suddenly and typically clears up in about four days. The term acute refers to how long your child has the infection, not to how serious the condition is.

Symptoms of acute middle ear infection

An acute middle ear infection can be triggered soon after your child gets a cough or a runny nose. Symptoms can include:

- earache

- deafness

- a high temperature

- a general feeling of being unwell, including feeling sick and loss of appetite

- irritability

- blood and pus coming out of the ear (if the eardrum bursts)

You may also notice your child tugging at his or her ear. As mucus and pus build up in your child's middle ear, he or she may feel as though their ear is blocked and it can be very uncomfortable. Eventually, the eardrum may burst as a result of the pressure, after this it's likely to be less painful. A burst eardrum usually heals by itself.

The symptoms of acute middle ear infection usually clear up on their own within four days. If you have any concerns about your child's symptoms or if they get worse at any time, see your GP.

Causes of acute middle ear infection

Your middle ear is normally filled with air, but can become filled with fluid if you have a virus, such as a cold. This is because the Eustachian tube can become swollen or blocked and the fluid can't drain away. The fluid in your middle ear can then become infected with bacteria, which travel up the Eustachian tube from your nose or throat. White blood cells that come to fight the infection can build up in your middle ear as pus. This build-up of pus can cause ear pain and hearing problems.

Acute middle ear infections are very common in children. This is partly because their immune systems are still developing and they are less well equipped to deal with infections than older children and adults. It's also because the Eustachian tube isn't fully developed in young children – it's quite short and horizontal, and so fluid and mucus can build up in the middle ear more easily.

An acute middle ear infection can also be caused by enlarged tonsils and adenoids. The adenoids are two small lumps of tissue similar to the tonsils, which sit at the back of your child's throat, beside the Eustachian tubes. If your child's adenoids are enlarged, they can block the Eustachian tube or, if inflamed, can cause inflammation of the Eustachian tube entrances.

Other factors that can increase the chance of your child getting an acute middle ear infection include:

- using a dummy

- formula feeding rather than breastfeeding, particularly if your child lies down when they feed

- passive smoking – if either parent smokes, a child is at higher risk

Boys tend to be affected more than girls and the condition is more common in winter than summer. Your child is also at increased risk if he or she has a lot of contact with other children, for example, at a nursery or playschool, or has lots of siblings. In addition, children who are born with a cleft lip or palate, or who have Down's syndrome are more likely to get middle ear infections.

Diagnosis of acute middle ear infection

Your GP will ask about your child's symptoms and examine your child. He or she may also ask about your child's medical history. He or she will use an instrument called an otoscope to look at your child's eardrum.

Your GP may refer you to have a tympanometry test, which is usually done by an audiologist – a technician or scientist who specialises in identifying and treating hearing and balance problems. This can measure how flexible your child's eardrum is – if your child has an acute middle ear infection, his or her eardrum stiffens up because of the fluid behind it.

If your child is under three months old, your GP may advise that you take him or her to hospital for further assessment.

Treatment of acute middle ear infection

Self-help

Often the best treatment for an acute middle ear infection is to relieve the symptoms with painkillers, such as paracetamol (eg Calpol) or ibuprofen (eg Nurofen for Children) while the inflammation clears up. Don't give aspirin to children under 16. Always read the patient information leaflet that comes with your medicine and if you have any questions, ask your pharmacist for advice. However, if your child's condition fails to clear up, or gets worse, see your child's GP.

Medicines

Most often, acute middle ear infections clear up on their own within four days and no antibiotics are needed. For this reason, your GP may give you a 'delayed prescription', one which you can't use until your child has had symptoms for at least four days. It's advised to use antibiotics sparingly to prevent antibiotic resistance building up.

However, if your child has already had symptoms for four days, your GP may prescribe antibiotics to start straight away. Also, if your child is under two and with both ears infected, or has a very high temperature or perforated ear drum then antibiotics may be prescribed sooner.

If your child is very young, under three months, your GP may recommend starting antibiotics straight away as well as referring your child to a hospital for further treatment.

If your child does have antibiotics, it's important to complete the course even if their symptoms get better.

Decongestant or antihistamine medicines are unlikely to help.

Always ask your GP for advice and read the patient information leaflet that comes with your medicine.

Surgery

If your child gets several acute middle ear infections in a six-month period, or if a burst eardrum takes longer than one month to heal, your GP may decide to refer him or her to an ear, nose and throat specialist. Your child may need surgery if he or she has recurrent infections (three or more infections within six months).

Surgery may involve a procedure called a myringotomy in which a small cut is made in your child's eardrum so that fluid can drain out. Ventilation tubes called grommets or tympanostomy tubes may also be inserted into the cut in your child's ear. These are small plastic tubes that allow air to get in and out of his or her ear. Ask your doctor for more information.

Prevention of acute middle ear infection

It's important to make sure that all your child's vaccinations are up to date, and take steps not to expose your child to tobacco smoke, including not smoking in your house or car.

You can also try, wherever possible, to prevent contact with unwell children to stop your child picking up an infection, as well as ensuring that your child washes his or her hands properly and has good basic hygiene.

Vaccines are currently being developed by scientists to help prevent acute middle ear infections. The vaccines, called pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs), aim to immunise young children against pneumococcal infections, which are a common cause of middle ear infections. Research has shown that one such vaccine may help to prevent acute middle ear infections, but more research is needed to prove it has a big enough effect.

Other research has shown that chewing gum that contains xylitol can reduce the number of acute middle ear infections in children.

This section contains answers to common questions about this topic. Questions have been suggested by health professionals, website feedback and requests via email.

How likely is my child’s middle ear infection to reoccur?

Is there anything else I can do to reduce the chance of my baby getting ear infections?

How can a dummy increase my baby’s risk of getting middle ear infection?

How likely is my child’s middle ear infection to reoccur?

Answer

Ear infection is more likely to re-occur in children who get it at a very young age.

Explanation

The individual risk that your child’s ear infection will re-occur can’t be predicted, as every child will respond differently when they have an ear infection.

However, it’s known that the younger a child is when they get an acute ear infection, the more likely it is to happen again. Studies have shown that six out of ten children who have their first bout of middle ear infection before the age of six months will have two or more recurrences in the next two years.

Younger children with acute ear infection are also more likely to develop glue ear, and in those who do get glue ear, it is more likely to be persistent (take longer to clear up).

Is there anything else I can do to reduce the chance of my baby getting ear infections?

Answer

Yes, breastfeeding your baby may help to reduce his or her chance of getting middle ear infections.

Explanation

Several studies have shown that babies who are breastfed have a reduced risk of getting middle ear infections compared to babies who aren’t breastfed. There is thought to be some benefit even if you breastfeed your baby for just three months, and breastfeeding for six months or more means your baby has an even lower chance of getting an infection.

Unlike formula milk, a mother’s breast milk contains many vital nutrients and antibodies, which help the baby to fight infection. Breastfeeding also helps to reduce your baby’s chance of getting a number of other infections and conditions, as well as having many benefits for the mother.

How can a dummy increase my baby’s risk of getting middle ear infection?

Answer

It’s not exactly clear how dummies increase the chance of getting a middle ear infection. It’s thought they may affect the flow of secretions from your baby’s nose and upper throat to the middle ear.

Explanation

There is evidence to suggest a number of benefits of using a dummy in younger babies. It’s thought that using a dummy helps to reduce pain during minor medical procedures and, when given as they go off to sleep, may reduce the risk of cot death.

However, sucking a dummy increases the flow of secretions from your baby’s throat to the middle ear. This can increase the risk of infection by allowing bacteria and viruses to enter the middle ear more easily. The dummy itself may also be contaminated with bacteria.

Using a dummy can also affect your baby’s tooth development and, as a result affect the function of his or her eustachian tube (the tube that connects the upper throat to the middle ear).

The main risk in using a dummy is thought to relate to recurrent middle ear infection – using a dummy in a child who has already had an infection is thought to increase the risk of his or her infection coming back.

The best advice is to try to discourage your child from using a dummy after six months of age to help prevent a first middle ear infection. You should also stop giving your child a dummy if he or she has already had an ear infection to reduce the risk of recurrence.

Further information

-

Deafness Research UK

020 7833 1733

www.deafnessresearch.org.uk

-

National Deaf Children's Society

0808 800 8880

www.ndcs.org.uk

-

Royal National Institute for Deaf people (RNID)

0808 8080123

www.rnid.org.uk

Sources

- Kozyrskyj AL, Klassen TP, Moffatt M, et al. Short-course antibiotics for acute otitis media. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 9. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001095.pub2

- Acute otitis media in children and adolescents – suspected. Map of Medicine. www.eng.mapofmedicine.com, published 2 February 2011

- Otitis media. Medscape. www.emedicine.medscape.com, published 8 December 2010

- Abba K, Gulani A, Sachdev HS. Zinc supplements for preventing otitis media. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 2. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006639.pub2

- Middle ear, tympanic membrane, perforations. Medscape. www.emedicine.medscape.com, published 25 September 2009

- Ear infections in children. National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. www.nidcd.nih.gov, published October 2010

- Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary. 62nd ed. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain; 2011

- Mcdonald S, Langton Hewer CD, Nunez DA. Grommets (ventilation tubes) for recurrent acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 4. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004741.pub2

- Jansen AGSC, Hak E, Veenhoven RH, et al. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines for preventing otitis media. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 2. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001480.pub3

Daly KA, Hoffman HJ, Kvaerner KJ, et al. Epidemiology, natural history, and risk factors: Panel report from the ninth international research conference on otitis media. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2010; 74:231–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.09.006 - Why breastfeeding is important. womenshealth.gov. www.womenshealth.gov, accessed 4 August 2011

- Reduce the risk of cot death. Department of Health. www.dh.gov.uk, published 2009

- Roversa MM, Numansa ME, Langenbacha E, et al. Is pacifier use a risk factor for acute otitis media? Fam Pract 2008; 25(4):233–36. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn030

- Glue ear. Action on Hearing Loss. www.actiononhearingloss.org.uk, May 2011

- Simon C, Everitt H, van Drop F. Oxford Handbook of General Practice. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010:944–45