Asthma

Asthma is a common condition that causes difficulty with breathing. Most people with asthma who take the appropriate treatment can live normal lives, but left untreated, asthma can cause permanent damage to the airways. Very rarely, a severe asthma attack can be fatal.

How an asthma attack occurs

About asthma

Symptoms of asthma

Causes of asthma

Diagnosis of asthma

Treatment of asthma

Asthma attacks – what to do

Living with asthma

How an asthma attack occurs

About asthma

Asthma is a common condition – it affects about five million people in the UK. It often starts in childhood, but it can happen for the first time at any age.

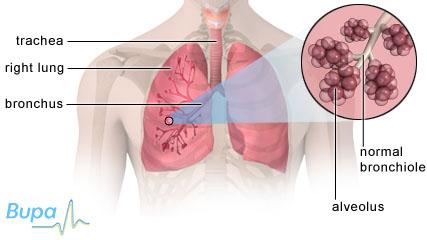

If you have asthma, your airways become irritated and inflamed. As a result, they:

- become narrower

- produce extra mucus

This makes it more difficult for air to flow into and out of your lungs.

Symptoms of asthma

Asthma symptoms may be mild, moderate or severe. They may include:

- coughing

- wheezing

- shortness of breath

- tightness in your chest

These symptoms tend to be variable and may stop and start. They are often worse at night.

Causes of asthma

The cause of asthma isn’t always clear. However, there are often triggers that can result in a flare up of symptoms. Common triggers include:

- respiratory infection – such as a cold or flu

- irritants – such as dust, cigarette smoke and fumes

- chemicals (and other substances) found in the workplace – this is called occupational asthma

- allergies to pollen, medicines, animals, house dust mites or certain foods

- exercise – especially in cold, dry air

- emotions – laughing or crying very hard can trigger symptoms, as can stress

- medicines – certain medicines can trigger asthma

In children, asthma is more common in boys than in girls but in adults, women are more likely to have asthma. Asthma often runs in families.

If you smoke during pregnancy, your baby is more likely to get asthma. If you smoke and have young children, they are more likely to get asthma. Premature or low birth weight babies are also more likely to develop asthma.

Diagnosis of asthma

Your doctor will ask about your symptoms and examine you. He or she may also ask you about your medical history. Your GP will ask if you have noticed any factors that trigger your symptoms.

Your GP may do one or more of the following tests to make a diagnosis.

- Peak flow measurement – this test measures how fast the air is expelled from your lungs.

- Spirometry – this test also measures the speed of the air flow as well as how much air is flowing; this provides more detailed information than a peak flow meter and can help show how well your lungs are functioning.

- Chest X-rays – these may be done to make sure you don’t have any other lung disease.

- Allergy test – this can help to find out whether you’re allergic to certain substances.

In children under five, a diagnosis may be made just by seeing if they respond to asthma treatments.

Treatment of asthma

There isn’t a cure for asthma. However, treatments are available to help manage your symptoms. Your treatment plan will be individual to you, combining medicines and asthma management in a way that works best for you.

Inhalers

Inhalers contain gas or dry powder that propels the correct dose of medicine either when you press the top down or when you inhale. The medicine is inhaled into your airways. You will need to use your inhaler correctly in order for it to work properly, so ask your GP for advice.

There are two basic categories of inhaler medicines that are used for asthma:

- relievers – to treat your symptoms

- preventers – to help prevent your symptoms

You should use relievers when your asthma symptoms occur. They can be short or long-acting. Short-acting relievers (known as bronchodilators) contain medicines such as salbutamol (eg Ventolin) and terbutaline (eg Bricanyl) that work to widen your airways and quickly ease your symptoms.

If you’re given a preventer you should use it every day – even if you don’t have symptoms. Preventers usually contain a steroid medicine, such as beclometasone (eg Qvar) or fluticasone (eg Flixotide) that work to reduce the inflammation of your airways. It can take up to 14 days for preventer medicines to work, but once they do, you may not need to use your reliever inhaler at all.

A long-acting reliever can be added to your treatment if your symptoms aren’t well controlled with a regular steroid (preventer) and occasional use of a short-acting reliever. Long-acting relievers contain medicines such as salmeterol (eg Serevent) or formoterol (eg Oxis). Often these medications are combined with steroid inhalers such as symbicort (eg Seretide).

-

Spacers If you use a gas propelled inhaler, you may also be given a spacer. Spacers are devices that can help you use your inhaler correctly and are particularly helpful for children – children as young as three can learn to use an inhaler with a spacer, and for babies and very young children a face mask can be attached. A spacer is a long tube which clips onto the inhaler. You breathe in and out of a mouthpiece at the other end of the tube.

It’s easier to use because it allows you to activate the inhaler and then inhale in two separate steps. Using a spacer also reduces the risk of getting a sore throat from using a steroid inhaler. When used correctly they can be as effective as nebulisers in the treatment of an acute asthma attack.

-

Nebulisers Nebulisers make a mist of water and asthma medicine that you breathe in. They can help to deliver more of the medicine to exactly where it’s needed. This is particularly important if you have a severe asthma attack and you require emergency treatment in the home or hospital setting. However, if you use a spacer with your asthma medicines it may be just as effective as a nebuliser at treating most asthma attacks.

If your child has asthma, ask your GP for advice as a nebuliser may not be suitable.

Other medicines

If you have severe asthma symptoms, your GP may prescribe a course of steroid tablets such as prednisolone.

Several other medicines are available as tablets and inhalers if the standard treatments aren’t suitable for you. These include montelukast (eg Singulair) or zafirlukast (eg Accolate).

Asthma attacks – what to do

If you have an asthma attack you should take the following steps.

- Take your reliever treatment immediately, preferably with a spacer.

- Sit down (don’t lie down) and try to relax.

- Wait five to 10 minutes – if there is no improvement repeat one puff of your reliever treatment every minute for five minutes until your symptoms go away.

- If your symptoms don’t go away, you should call your GP or an ambulance, but continue taking your reliever, preferably with a spacer, every few minutes until help arrives.

- If you go to hospital, take your asthma treatments with you.

Make sure you see your GP so he or she can review your treatment.

Living with asthma

Medicines are only part of your treatment for asthma. You will also need to deal with the things that make it worse. Keep a diary to record anything that triggers your asthma – this can help you to discover a pattern. Using a peak flow meter to monitor your lung function can also help. If you have repeatedly low readings in a certain situation (for example, at the end of a working day, after exercise or after contact with an animal) this may indicate the trigger.

Stopping smoking is good for your health and will improve your asthma symptoms.

With good management and appropriate treatment, most people with asthma lead completely normal lives.

What is occupational asthma?

Will pregnancy make my asthma symptoms worse? Should I still take my asthma medicines?

What is exercise-induced asthma?

My child has just been diagnosed with non-wheezy asthma, what is it?

Can passive smoking cause asthma in children?

Can children grow out of their asthma?

Can breastfeeding help to prevent asthma?

What is occupational asthma?

Occupational asthma is an allergic reaction that can occur when you are exposed to certain chemicals and other substances in your workplace. People most at risk include bakers, woodworkers and spray painters.

Explanation

Over 200 industrial materials are known to cause occupational asthma, and it’s estimated that between 1,500 and 3,000 people in the UK develop the condition each year. Occupational asthma can occur as a result of exposure to substances such as flour or wood dust found where you work. These substances can make your airways become hypersensitive. With repeated exposure to these substances, you are more likely to have problems with asthma.

According to the Health and Safety Executive (HSE), the following jobs are at the highest risk of developing occupational asthma.

- Bakers – caused by the flour and enzymes used in the baking process.

- Vehicle spray painters – caused by the chemicals used in spray paints.

- Metal workers (solderers) – caused by the fumes used when soldering.

- Woodworkers – caused by hardwood, softwood and wood dusts from wood machining and sanding.

- Healthcare workers – caused by powdered latex gloves, and biocides and chemical disinfectants.

- Laboratory animal workers – caused by contact with animals, animal handling and cage or enclosure cleaning.

- Agricultural workers – caused by grain dust from harvesting, moving and processing cereal crops.

- Engineering workers – caused by the mist or vapour from metalworking fluids during machining or shaping operations.

It can be difficult to know if your job is causing your asthma. Symptoms don’t always occur as soon as you have been exposed to the substance, they can occur after work or at night. You may find that your asthma symptoms improve when you have a day off work or are on holiday.

If you have asthma symptoms, it’s important to see your GP. He or she may refer you to a respiratory physician – a doctor who specialises in treating and identifying lung conditions.

The HSE website has tips on what high-risk professions can do to prevent occupational asthma in their workplace.

If you have any questions or concerns about occupational asthma, talk to your GP.

Will pregnancy make my asthma symptoms worse? Should I still take my asthma medicines?

Being pregnant usually has little or no effect on asthma. You should continue taking your asthma medicines as normal throughout your pregnancy.

Explanation

For most women with well controlled asthma, the condition has no effect on their pregnancy, giving birth or their baby.

However, women with severe asthma may find that their symptoms get worse during pregnancy. If you have severe asthma, it’s important to see your GP on a regular basis to make sure your symptoms are well controlled. If you have problems, your GP may refer you to a respiratory physician. A respiratory physician is a doctor who specialises in treating and identifying lung conditions.

Poorly controlled asthma symptoms during pregnancy have been linked with a number of complications including low birth weight, premature birth and pre-eclampsia. Also, if you smoke, it's important to quit as smoking lessens the effect of your asthma treatment and poses long-term health risks to you and your baby.

During pregnancy, it’s very important to continue taking your asthma medicines as usual. Your GP may wish to monitor you more closely so that your medicine can be adjusted in response to any changes. It may be helpful to talk to your GP before becoming pregnant. If you smoke, he or she can give you advice on quitting.

Standard asthma treatments such as bronchodilators (salbutamol, terbutaline, theophylline) and inhaled corticosteroids are safe to take before, during and after your pregnancy (including while breastfeeding).

If you have any questions or concerns about asthma and pregnancy, talk to your GP.

What is exercise-induced asthma?

Exercise-induced asthma is when you get symptoms of asthma during or shortly after doing physical exercise. This can happen even if you don’t have asthma symptoms at any other time.

Explanation

Exercise is a common trigger of asthma. It’s not clear exactly how it brings on symptoms, but it’s thought to be related to breathing in cold, dry air. When you breathe fast during exercise, it’s more difficult for your nose and upper airways to warm and add moisture to the air coming in. This means that the air going into your airways is colder and drier than usual.

Symptoms of exercise-induced asthma can include:

- coughing

- wheezing

- shortness of breath

- tightness in your chest

You may find that your symptoms begin with exercise and worsen until about 15 minutes after you have stopped. Also, you may only have symptoms during or after exercise and not at any other time. It’s important that you see your GP for a diagnosis and treatment if you have these symptoms with exercise.

Treatment is usually with a short-acting relieving inhaler. Or you may be prescribed inhaled steroids or longer-acting beta2 agonists. The short-acting inhalers need to be used before you start exercising.

Some forms of exercise may make your symptoms worse than others. Long-distance cross-country running can bring on symptoms because of the cold air and because you are active for a long period of time with no breaks. Team sports, such as netball and football, are less likely to bring on symptoms because they are usually made up of short bursts of activity followed by rest breaks. Swimming is a great exercise for people who have asthma because of the warm, humid air around the pool. Relaxation exercises and yoga may also be helpful to relax your body to focus on your breathing.

If you are planning to do any adventure sports, such as scuba-diving, mountaineering or skiing, it’s important that you talk to your GP first and make sure you inform the instructor leading the activity.

If you already have asthma and are receiving treatment, but you are still getting asthma symptoms when exercising, it’s important that you see your GP. This is usually a sign that your asthma is not being properly controlled.

If you have any questions or concerns about exercise-induced asthma, talk to your GP.

My child has just been diagnosed with non-wheezy asthma, what is it?

Non-wheezy asthma is when you have asthma without any wheezing – instead you have a dry cough. This type of asthma can affect both children and adults.

Explanation

One of the most recognisable symptoms of asthma is wheezing. However, it is possible to have asthma without any wheezing – instead your main symptom is a dry cough. This type of asthma is also called atypical asthma, hidden asthma, cough-variant asthma and cough-type asthma. It’s common in families that have a history of allergies, and, although it can affect anyone at any age, it’s the most common cause of long-term coughing in children.

The cough is dry and repetitive, and your child may have it during the day but it mainly occurs at night. You may find that it gets worse if he or she has a cold, when he or she is exercising or breathing in cold air. If your child has any of these symptoms, it’s important to see your GP to get a diagnosis and treatment.

Treatment for non-wheezy asthma is the same as for regular asthma. Your child will be prescribed a short-acting inhaler (reliever) such as salbutamol (eg Ventolin), and/or an inhaled steroid medicine (preventer) such as beclometasone (eg Asmabec).

If you have any questions or concerns about non-wheezy asthma, talk to your GP.

Can passive smoking cause asthma in children?

Yes, there is evidence to show that passive smoking can cause asthma and other respiratory symptoms in children.

Explanation

Passive smoking is when you breathe in other people’s second-hand smoke. Passive smoking is potentially harmful to everyone, but especially to children. When children are growing, their lungs are still developing and can be particularly sensitive to pollutants in the air. Babies can also be affected by smoking when they are still in the womb.

Studies have shown that exposure to tobacco smoke in the home can increase the risk of your child developing asthma and can cause asthma attacks. In children who already have asthma, it can make their symptoms much worse.

All children – whether they have asthma or not – should be kept away from smoky atmospheres. If you have children or are pregnant and smoke, you should consider quitting. Your GP can give you support and advice on how to stop smoking.

If you aren’t ready to quit, try not to smoke around your children. Smoke outside rather than indoors. Cigarette smoke can linger for several hours in a room after you have stopped, so your children will continue to be exposed until it has completely disappeared. If you are going to be spending long periods of time with your family (for example, when you are on holiday) try using nicotine replacement products instead of smoking.

If you have any questions or concerns about passive smoking and asthma, talk to your GP.

Can children grow out of their asthma?

Yes, some children who have asthma will have fewer symptoms as they get older and may become symptom-free by the time they are adults.

Explanation

Over a million children in the UK have asthma. Asthma symptoms improve with age in most children with asthma. Those who have mild, infrequent symptoms will often grow out of the condition altogether.

For children who have frequent asthma symptoms or have chronic asthma, the chances of their condition disappearing when they are older are far less likely. This risk is further increased if your child:

- has ongoing eczema

- has chronic lung disease

- starts smoking at a young age

If you have any questions or concerns about your child’s asthma, talk to your GP.

Can breastfeeding help to prevent asthma?

Yes, some research has shown that breastfeeding your baby can help reduce his or her risk of developing asthma.

Explanation

Breastfeeding your baby has many long-term health benefits. It has been found that breastfeeding can help prevent many health conditions, including ear infections, stomach upsets, eczema and asthma.

Research into the effects of breastfeeding on asthma found that breastfed babies, without a family history of asthma, were less likely to develop asthma than those who were fed on formula milk. For babies with a family history of asthma, the results were less clear.

It’s recommended that all babies are breastfed for the first six months of their life without any water, other fluids or solid foods. After this time, they can be introduced to solid foods and fluids as well as continuing with breast milk.

If you have any questions or concerns about asthma and breastfeeding, talk to your GP.

Further information

Asthma UK

0800 121 6244

www.asthma.org.uk

British Lung Foundation

08458 50 50 20

www.lunguk.org

National Childbirth Trust

0300 33 00 771 (breastfeeding line)

http://nct.org.uk

Sources

- Asthma. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. www.cks.nhs.uk, accessed 20 April 2010

- Asthma. British Lung Foundation. www.lunguk.org, accessed 20 April 2010

- What is asthma? Asthma UK. www.asthma.org.uk, accessed 20 April 2010

- Asthma triggers A–Z. Asthma UK. www.asthma.org.uk, accessed 20 April 2010

- British guideline on the management of asthma: A national clinical guideline. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), June 2009, 101. www.sign.ac.uk

- Passive smoking and children. Tobacco Advisory Group of the Royal College of Physicians, March 2010. www.rcplondon.ac.uk

- Inhaled corticosteroids for the treatment of chronic asthma in adults and in children aged 12 years and over. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), March 2008, 138. www.nice.org.uk

- Management of chronic asthma. British National Formulary. http://bnf.org, accessed 20 April 2010

- Salbutamol. British National Formulary. http://bnf.org, accessed 20 April 2010

- Terbutaline sulphate. British National Formulary. http://bnf.org, accessed 20 April 2010

- Beclometasone dipropionate. British National Formulary. http://bnf.org, accessed 20 April 2010

- Fluticasone propionate. British National Formulary. http://bnf.org, accessed 20 April 2010

- What to do in an asthma attack? Asthma UK. www.asthma.org.uk, accessed 20 April 2010

- Medicines and treatments. Asthma UK. www.asthma.org.uk, accessed 20 April 2010

- Cates CJ, Crilly JA, Rowe BH. Holding chambers (spacers) versus nebulisers for beta-agonist treatment of acute asthma. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD000052. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000052.pub2

- Occupational asthma: A guide for employers, workers and their representatives. British Occupational Health Research Foundation. www.bohrf.org.uk, accessed 21 April 2010

- Asthma. Health and Safety Executive. www.hse.gov.uk, accessed 21 April 2010

- Exercise-induced asthma. Asthma UK. www.asthma.org.uk, accessed 21 April 2010

- Novey H. Asthma without wheezing. Western J Med 1991; 154(4):459–60

- Asthma and allergies. World Health Organization. www.euro.who.int, accessed 21 April 2010

Published by Bupa’s health information team, July 2010