Coronary heart disease

Coronary heart disease is due to fatty deposits building up on the walls of the arteries to the heart. It causes angina, which is chest pain.

In the UK, more people die from coronary heart disease than from any other cause.

How atherosclerosis develops

About coronary heart disease

Symptoms of coronary heart disease

Causes of coronary heart disease

Diagnosis of coronary heart disease

Treatment of coronary heart disease

Prevention of coronary heart disease

How atherosclerosis develops

The information on the video provided does not constitute advice on diagnosis or the treatment for heart disease and such advice should always be sought from a doctor or another suitably qualified health professional.

About coronary heart disease

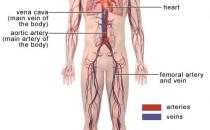

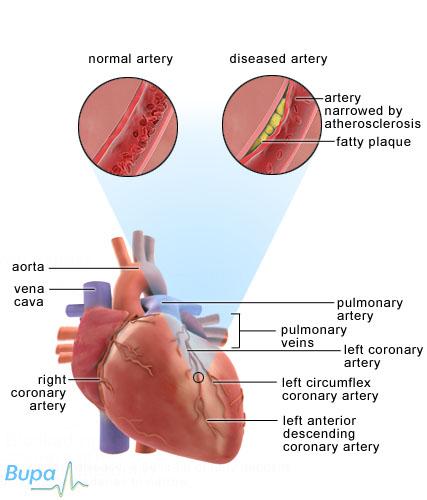

Your heart is a pump that circulates blood to your lungs and the rest of your body. The surface of your heart is covered with blood vessels called coronary arteries, which supply your heart muscle with blood.

Coronary heart disease happens when fatty deposits build up on the walls of your coronary arteries. This is known as atherosclerosis.

In atherosclerosis, fat and cholesterol in your blood builds up on your artery walls, forming a plaque or atheroma. The plaque can prevent your heart muscle from getting the blood supply it needs. Because of the reduced blood flow and the rough edges of the plaque, a blood clot sometimes forms, blocking your artery.

Sometimes the plaque may rupture, which also causes your blood to clot. This is called atherothrombosis. Atherothrombosis stops an area of your heart muscle receiving blood and oxygen, leading to a heart attack. If a lot of your heart muscle is damaged, your heart may stop beating regularly. Sometimes the damage causes your heart to stop beating altogether, which is fatal.

Symptoms of coronary heart disease

Coronary heart disease develops slowly over many years. In some people, breathlessness when exercising is the only symptom. You may not know anything is wrong until you develop angina (chest pains) or have a heart attack.

Angina

Angina is the feeling of chest pain, chest tightness, and sometimes breathlessness or choking. It happens when blood flow in the arteries that supply your heart is restricted.

Angina typically starts when you’re walking or feeling upset. It can also be brought on after a meal and by cold weather. Symptoms include:

• discomfort or a tightening across your upper chest - this may be confused with indigestion

• pain radiating to your neck, jaw, throat, back or arms for a few minutes, disappearing quickly after resting

• breathlessness

• sweatiness

Angina can be treated with lifestyle changes and medicines. Left untreated, it will become more frequent and the pain will get worse. Having angina means you’re at a higher risk of having a heart attack.

Heart attack

Most heart attacks cause severe pain in the centre of your chest and can feel like very bad indigestion. Symptoms can happen suddenly, but sometimes the pain develops more slowly. Symptoms include:

• a feeling of heaviness, squeezing or crushing in the centre of your chest

• pain may spread to your arms, neck, jaw, face, back or stomach, lasting for hours

• loss of consciousness

• sweatiness and breathlessness

• feeling or being sick

Sometimes there are no symptoms at all. This is called a silent myocardial infarction. Older people and people with diabetes are more likely to have this kind of heart attack.

Call an ambulance immediately if you suspect someone is having a heart attack. Give him or her 300 mg aspirin to chew or to swallow dissolved in water. This helps prevent the clot that is blocking his or her coronary artery from growing.

Arrhythmia

An arrhythmia is an irregular heart beat. Sometimes this can be felt as a heart palpitation (a sensation of a skipping or thumping heart beat). Sometimes palpitations are a symptom of coronary heart disease. However, heart palpitations are common, and don't necessarily mean that you have either coronary heart disease or an arrhythmia.

Heart failure

Over time, coronary heart disease may weaken your heart, leading to heart failure. Heart failure means that your heart isn't strong enough to pump blood around your body effectively and you get tired and out of breath easily. It can also lead to swelling in your ankles and legs.

Causes of coronary heart disease

Coronary heart disease is caused by the build up of fatty deposits on your artery walls.

Coronary heart disease is more common in older people. Up to the age of 65, it’s more common in men than women. It's also more common among people from India and Pakistan.

Factors that increase your risk of developing coronary heart disease include:

• smoking

• being overweight, especially if you have excess fat around your tummy

• an inactive lifestyle

• diabetes

• high blood pressure

• high cholesterol

Diagnosis of coronary heart disease

Your doctor will ask about your symptoms and examine you. You will need to have some tests, which may include the following.

• Blood tests.

• Electrocardiogram (ECG) – a test that measures the electrical activity of your heart to see how well it’s working. You may have an exercise ECG, which means the test is done while you’re walking on a treadmill or pedalling on an exercise bike.

• Echocardiogram – a test that uses ultrasound to produce a moving 'real-time' image of the inside of your heart.

• A coronary angiogram – a test that uses an injection of a special dye into the blood vessels of your heart to make them clearly visible on X-ray images.

• Radionuclide tests – for this test your doctor will give you a small, harmless injection of radioactive material, which passes through your heart muscle. A large camera directed at your heart picks up rays sent out by the radioactive material and creates an image of your heart.

• Chest X-ray.

• MRI scan.

• Electrophysiological tests – a catheter is put into a blood vessel in your groin and guided to your heart. The tip of the catheter stimulates your heart and records the electrical activity.

Treatment of coronary heart disease

Treatment for coronary heart disease depends on how serious it is. There are several treatments available. If you have angina or have had a heart attack, angioplasty or surgery may be the best treatment option.

Medicines

Medicines aim to stop coronary heart disease getting worse or prevent further heart attacks. Some examples are listed below.

• Anti-platelet medicines such as asprin. Taking a small (75 mg) daily dose of aspirin makes your blood less likely to form clots, reducing your risk of having a heart attack.

• Cholesterol-lowering medicines, such as statins, which slow down the process of atherosclerosis.

• Beta-blockers reduce your blood pressure and the amount of work your heart does.

• Calcium channel blockers relax and widen your arteries.

• Anticoagulants help to stop blood clots forming.

• ACE inhibitors lower your blood pressure and are often used in people with heart failure or after a heart attack.

• Nitrates relax your coronary arteries, allowing more blood to reach your heart.

• Anti-arrhythmic medicines help to control your heart rhythm.

Always ask your doctor for advice and read the patient information leaflet that comes with your medicine.

Non-surgical treatment

A coronary angioplasty involves your doctor passing a collapsed balloon through your blood vessels until it reaches the arteries of your heart. The balloon is inflated to widen your narrowed coronary artery. A stent (flexible mesh tube) is sometimes inserted to help keep your artery open afterwards.

Surgery

Your surgeon may recommend a coronary artery bypass graft (CABG). This means he or she will take a piece of a blood vessel from your leg or chest and use it to bypass the narrowed coronary arteries. The bypass provides your heart with more blood.

Prevention of coronary heart disease

Coronary heart disease can be prevented in most people by adopting a healthy lifestyle.

You can reduce your chance of having a heart attack by:

• not smoking

• losing excess weight

• doing regular physical activity, for 30 minutes at least five days a week

• eating a low fat and high fibre diet with five portions of fruit and vegetables a day and two portions of fish (one oily) a week

• not exceeding four units of alcohol a day for men or three units for women

Answers to questions about coronary heart disease

This section contains answers to common questions about this topic. Questions have been suggested by health professionals, website feedback and requests via email.

Can I drive a car if I have coronary heart disease?

If I have had a heart attack, when can I go back to work?

Can I have sex if I have coronary heart disease?

Can I drive a car if I have coronary heart disease?

It depends. If you have angina, then you can only drive if your symptoms are under control. Your doctor will be able to give you more advice.

Explanation

If you have coronary heart disease, it can be dangerous for you to drive. An episode of angina or a heart attack might cause you to crash your car. Because of this the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) has a set of guidelines that give advice on who is safe to drive and who isn't.

If you have angina, you must stop driving until your symptoms are under control. Your GP will be able to advise you on this.

Check your insurance policy as you may need to inform your insurance company of your condition.

If I have had a heart attack, when can I go back to work?

This can depend on lots of things, including how much damage has been caused to your heart and what type of work you do.

Explanation

You will need time to recover after you have had a heart attack. When you’re able to return to work will depend partly on the type of work you do. If you do manual work, such as lifting objects or operating heavy machinery, you shouldn't be working if this causes any chest pain, breathlessness or palpitations. The amount of stress involved in your job may also play a part in when you can return to work. Ask your doctor when you will be fit enough to go back to work.

You may want to talk to your employer about returning to work part-time at first. Your employer may also be able to offer you help from an occupational therapist who can adapt your work environment to help you return to work.

Can I have sex if I have coronary heart disease?

Yes, most people can continue to have a healthy sex life after being diagnosed with coronary heart disease.

Explanation

Some people worry they won't be able to have sex after a heart attack or with coronary heart disease, but this isn't usually the case. Sex is like any other form of exercise. You need to talk to your doctor before starting exercise after you have had a heart attack or surgery.

You may be advised to take things slowly, and to wait four to six weeks before having sex. If you have chest pain or breathlessness caused by sex or any other form of exercise, tell your doctor.

You may feel that your sex drive has reduced after a heart attack or surgery, but it will usually come back after plenty of rest. Depression is fairly common after having a heart attack, and this can also affect your sex drive but it usually improves after a few months.

Coronary heart disease can increase the risk of impotence in men. If atherosclerosis has narrowed the blood vessels in your penis, it can make it difficult for you to achieve an erection. Rarely, medicines you’re taking to treat coronary heart disease, such as beta-blockers or diuretics, can affect your sex drive. If you have any problems, talk to your GP.

Keywords: coronary heart disease, angina, drive, heart attack, work, sex

Further information

• British Heart Foundation

020 7935 0185

www.bhf.org.uk

Sources

• Coronary heart disease. Department of health. www.dh.gov.uk, accessed 16 December 2009

• Prevalence of all coronary heart disease. British Heart Foundation. www.heartstats.org, accessed 16 December 2009

• What Is Coronary Artery Disease? National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. www.nhlbi.nih.gov, accessed 16 December 2009

• The heart. The British Heart Foundation. www.bhf.org.uk, accessed 16 December 2009

• Simon, C, Everitt, H, Kendrick, T. Oxford handbook of general practice. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005: 314, 332, 1048

• Obesity and health. Bandolier. www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/bandolier, accessed 16 December 2009

• More on risk factors and initiatives to promote a healthier lifestyle. Department of Health. www.dh.gov.uk, accessed 16 December 2009

• Angina. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. www.cks.nhs.uk, accessed 16 December 2009

• Angina. The British Cardiac Patients Association. www.bcpa.co.uk, accessed 16 December 2009

• Heart attack. British Heart Foundation. www.bhf.org.uk, accessed 16 December 2009

• FAQs. British Heart Foundation. www.2minutes.org.uk, accessed 16 December 2009

• Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary. 53rd ed. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 2006:131

• Heart rhythms. British Heart Foundation. www.bhf.org.uk, accessed 16 December 2009

• Heart failure. British Heart Foundation. www.bhf.org.uk, accessed 16 December 2009

• Tests. British Heart Foundation. www.bhf.org.uk, accessed 16 December 2009

• Medicines for the heart. British Heart Foundation. www.bhf.org.uk, accessed 16 December 2009

• Coronary Angioplasty. British Heart Foundation. www.bhf.org.uk, accessed 16 December 2009

• Coronary bypass surgery. British Heart Foundation www.bhf.org.uk, accessed 16 December 2009

• Valve replacement. British Heart Foundation. www.bhf.org.uk, accessed 16 December 2009

• Cardiovascular risk assessment and management – management. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. www.cks.nhs.uk, accessed 16 December 2009

• Smoking. British Heart Foundation. www.heartstats.org, accessed 16 December 2009

• Overweight and obesity. British Heart Foundation. www.heartstats.org, accessed 16 December 2009

• Tests for heart conditions. British Heart Foundation. March 2009. www.bhf.org.uk

Related topics

• Angina

• Angiogram (cardiac catheterisation)

• Arrhythmia (palpitations)

• Beta-blockers

• Cardiovascular system

• Coronary angioplasty

• Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG)

• Depression

• Diagnosing heart conditions

• Diuretics

• Echocardiogram

• Electrocardiogram

• Giving up smoking

• Healthy eating

• Heart attack

• Heart failure

• High blood pressure (hypertension)

• High cholesterol

• Impotence

• Looking after your heart

• MRI scan

• Physical activity

• Sensible drinking

• X-ray

This information was published by Bupa's Health Information Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been peer reviewed by Bupa doctors. The content is intended for general information only and does not replace the need for personal advice from a qualified health professional.

Published by Bupa's Health Information Team, April 2010.