Glue ear

Glue ear is very common in children – approximately four out of five children will have had the condition at least once by the time they are four years old. The medical name for glue ear is otitis media with effusion. If a child has glue ear, it means there is a build-up of fluid in the middle ear, which can affect his or her hearing. Some children may need surgery to help clear the ear.

How glue ear develops

The middle ear

About glue ear

Symptoms of glue ear

Causes of glue ear

Diagnosis of glue ear

Treatment of glue ear

How glue ear develops

The middle ear

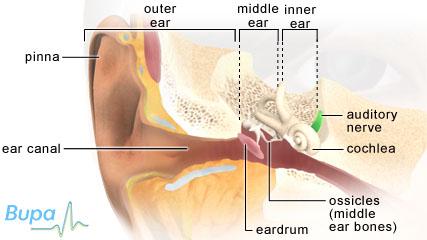

The middle ear is behind your eardrum. It contains three tiny bones that move when sounds reach them. These transmit sound waves through your middle ear to your inner ear. Usually, your middle ear is filled with air but if you have inflammation, fluid and mucus can build up there. The eustachian tube connects your middle ear with your throat.

About glue ear

Glue ear occurs when fluid and mucus collect in the middle ear behind the ear drum. This often happens after a middle ear infection or other condition that causes inflammation there.

Your child can get glue ear if the eustachian tube becomes blocked and fluid can't drain from the middle ear. A blocked eustachian tube can also stop air from getting into the middle ear. The air that is trapped in the middle ear is absorbed, reducing the pressure inside your child's ear and pulling the eardrum inwards. A sticky fluid builds up inside the middle ear and affects hearing, since the middle ear is filled with liquid rather than air.

Symptoms of glue ear

Unlike a middle ear infection (acute otitis media) where there is often earache, a high temperature and other signs of illness, with glue ear your child won't necessarily complain of any symptoms. The main problem is hearing loss and a feeling of the ear being "bunged up". This can come on gradually and therefore your child may not notice. The hearing loss is similar to wearing earplugs.

As a result of this hearing impairment, your child may have problems paying attention or interacting with others, as well as with his or her speech and language. Your child may also appear clumsy and have trouble with balance.

Causes of glue ear

Children under six are most at risk of glue ear because their eustachian tubes are shorter and more horizontal. This means that they get blocked more easily. Boys tend to be affected more than girls and the condition is more common in winter than summer.

Over half of all children with glue ear get it as a result of a bout of inflammation of the middle ear (acute otitis media).

If your child has nasal allergies to pets or dust, or has hay fever, he or she may be more likely to develop glue ear. Inflammation caused by the allergic reaction may cause their eustachian tube to swell and become blocked more easily. This may be the cause of glue ear if your child keeps getting it, even after he or she has had treatment.

Glue ear may also be caused by enlarged adenoids – these are two lumps of tissue at the back of the nose where it meets the throat. Adenoids help to fight infections but if your child's are enlarged, they can block the eustachian tube.

Other reasons why your child may be more likely to develop glue ear include:

- smoking in the house or in the car that is used to transport him or her

- repeated colds and throat infections

- having brothers or sisters with glue ear

- bottle-feeding

Your child is also at an increased risk if he or she has a lot of contact with other children, for example at a nursery or playschool. In addition, children who are born with a cleft lip or palate, or who have Down's syndrome are more likely to get middle ear infections and so are more susceptible to glue ear.

Diagnosis of glue ear

Your GP will ask about your child's symptoms and medical history. He or she will use an instrument called an otoscope to look at your child's eardrum.

For most children, glue ear doesn’t become long-term problem. At least half of children with glue ear get better within three months and only one in 20 are affected for longer than a year.

A child who has persistent glue ear or repeated bouts of it may need to be monitored to make sure his or her hearing and language isn’t affected. After your child has a bout of glue ear, your GP may suggest you bring him or her back in two to three months for a check-up. The doctor may ask for extra information from the school (if relevant) and refer you to a speech and language therapist.

Treatment of glue ear

After three months of monitoring, if the condition isn't improving, your GP may suggest that your child has a hearing test. He or she may refer your child to an otolaryngologist (a doctor specialising in conditions affecting the ear, nose and throat) or an audiological paediatrician (a doctor specialising in conditions affecting children's hearing). Your GP may also refer your child to a specialist if there is a persistent foul-smelling discharge from the ear, severe hearing loss or if he or she has a disability such as Down’s syndrome.

Non-surgical treatments

Antibiotics, antihistamines and decongestants aren’t recommended for glue ear. There is a possibility that your child may have side-effects to antibiotics. There is also no evidence that homeopathy, cranial osteopathy or special diets help with glue ear.

Once your GP has diagnosed persistent glue ear, it's important that your child has regular hearing checks. A hearing aid may be useful if surgery isn’t acceptable.

There is some evidence that a technique called autoinflation may help children with glue ear. Your child uses his or her nose to inflate a special balloon (called an Otovent, which can be bought from some pharmacies). This increases pressure in the nose and may help to open up the eustachian tube. This aims to let air into the middle ear so the fluid there can drain out. Some studies have shown this technique to be helpful in the short term, but more research is needed into the long-term effects.

Your GP will be able to give you more information about the treatment options that are available.

Surgery

After carefully monitoring your child’s condition for three to six months, your doctor may suggest surgery. Surgery is recommended for children who have severe hearing loss.

Surgery may involve a procedure called a myringotomy in which a small cut is made in your child's ear drum so that fluid can drain out. Ventilation tubes called grommets or tympanostomy tubes may also be inserted into your child's ear. These are small plastic tubes which are placed in a cut made in your child's eardrum. Grommets allow air to get in and out of the ear. They can be effective at improving hearing for up to two years but don't appear to offer any benefit in the long term. Grommets usually fall out after about six months to a year. Half of all children who have grommets inserted need to have another set put in after the first ones fall out.

If your child has grommets, it's fine to go swimming although diving and putting his or her head underwater (even in the bath) isn't recommended.

It may help your child to have an operation to remove his or her adenoids. This is called an adenoidectomy. However, the operation alone doesn't seem to improve hearing unless grommets are also inserted.

As with all surgery, there are some risks involved with inserting grommets or having an adenoidectomy. These include infection or, with grommets, the possibility of permanent damage to your child's eardrum. Discuss the risks with your child’s surgeon.

This section contains answers to common questions about this topic. Questions have been suggested by health professionals, website feedback and requests via email.

How will I know if my child's hearing is affected?

What kind of tests will my child have?

Do I need to take any precautions after my child's operation for grommets?

How will I know if my child’s hearing is affected?

Hearing loss can be difficult to identify because an affected child may not be aware of it. You child may mishear what you say and have trouble hearing you in a noisy environment or when you aren’t looking at him or her. Hearing problems can also affect behaviour and balance so your child might seem more clumsy than usual, have trouble concentrating or become frustrated or irritable.

Explanation

Hearing problems are one of the few clear features of glue ear but they can be hard to spot, particularly if your child is very young and can’t tell you that he or she is having trouble hearing. Hearing problems caused by glue ear also come and go, which makes it even harder to notice any hearing loss.

To a child with glue ear, sounds can seem muffled rather than disappearing completely. Sometimes it might seem like your child is only hearing you when he or she wants to. You may not notice any problems at home, but your child’s teacher, playgroup leader or nursery worker might do. Some things to look out for are described here.

-

Your child may mishear what you say, particularly when you’re talking and he or she isn’t looking directly at you. Your child may also have trouble hearing sounds that come from outside the area that he or she can see. Your child may often ask you to repeat what you have said or have trouble hearing in a noisy environment.

-

Your child might say “what?”, “eh?” or “pardon?” more than he or she usually does and might need the television volume turned up.

-

Because your child can’t hear well, he or she might start to behave differently. Children can become withdrawn or have trouble concentrating, which can lead to frustration and irritability. Once your child becomes tired, this can also lead to temper tantrums and over activity.

-

Children with glue ear can seem like they are daydreaming or not paying attention either at home or at school or nursery.

-

If your child is a baby or very young when he or she develops glue ear, this sometimes leads to a delay in the development of speech. For older children, hearing loss can affect other language skills such as reading and writing. They may also start to struggle at school.

-

Glue ear can cause balance problems too. This is because of the inflammation in the middle ear irritating the balance system of the inner ear. Your child might seem to be more clumsy than usual or have trouble with balance.

If you’re worried that your child may have hearing loss, talk to other people who spend time with him or her to see whether they have noticed any of the signs listed above and then see your GP for advice.

If your child is found to have glue ear and hearing problems, make sure that playgroup or nursery staff and teachers know, so that they can help your child during class. You may also find it helps to:

-

speak to your child face to face and at his or her level

-

get your child’s attention before you start talking to him or her – call your child’s name or use touch

-

speak clearly with a normal volume and rhythm – don’t shout

-

cut down background noise as much as possible, for example turn off the television

-

be direct and simple in what you say and check that your child understands what you have said

-

if your child has a close friend, you may want to tell his or her parents about the glue ear

What kind of tests will my child have?

Audiometry, tympanometry and otoscopy are the main tests used to find out whether your child has glue ear and whether his or her hearing is affected. Audiometry tests your child’s hearing using sounds of different volumes and tones. Tympanometry tests how flexible the eardrum is, which can help to diagnose glue ear. Otoscopy tests to see whether your child has any fluid behind his or her eardrums.

Explanation

There are two main tests used to find out whether a child has glue ear and whether the glue ear is affecting his or her hearing. These are audiometry and tympanometry. Both of these tests are usually done by an audiologist – a technician or scientist who specialises in identifying and treating hearing and balance problems. Your GP can refer your child to a community paediatric audiology clinic at your local hospital for these tests.

Tympanometry is a test to find out how well your child’s eardrum is working. A healthy eardrum is flexible and allows sound to pass through it and into your middle and inner ear. If your child has glue ear, his or her eardrum stiffens up because of the fluid behind it. Sound bounces off it rather than passing through.

The stiffness can be measured and can show whether or not your child has glue ear. Other conditions, such as problems with the middle ear bones, can also cause a stiff eardrum.The test is painless and takes just a few minutes to do. Tympanometry can be done with babies and young children because it doesn’t test hearing and doesn’t rely on getting a reaction from your child. A small earpiece with a soft rubber tip is placed just inside your child’s ear. A pump then causes the pressure in the ear to change and measures the amount of sound bounced back. The results show up straight away.

Audiometry tests your child’s hearing. There are a number of different ways of doing an audiometric test depending on how old your child is. All of the tests are looking to see your child’s reaction to sounds that have different volumes and pitch.

If your child is old enough to go to school, during the test he or she will usually be asked to wear head- or earphones and press a button when a sound is played. If your child is younger, the test is likely to be done as part of a game. Your child might be asked to put a peg on a board when he or she hears a sound. Children aged between nine months and about two and a half years may be tested using something called visual reinforcement audiometry (VRA). Different sounds will be played and when your child hears them he or she will turn towards the sound. As your child does this, he or she will be given a reward, for example the toy will light up. The tester can gradually turn down the volume of the sound to find out the quietest sound your child can hear.

Do I need to take any precautions after my child’s operation for grommets?

Recovery from an operation to have grommets put in is usually straightforward and most children have no problems. Different surgeons may give slightly different advice about dos and don’ts. Generally, it’s considered safe for your child to go swimming a couple of weeks after the operation but he or she shouldn’t dive or swim underwater. Your child should wear earplugs when he or she has a bath or shower or when washing his or her hair.

Explanation

The hole made in your child’s eardrum when grommets are put in is very small so it’s uncommon for infection to develop or for your child to have problems with normal day-to-day activities.

It’s safe for your child to go swimming a couple of weeks after a grommet operation but he or she should only swim on the surface of the water. Your child shouldn’t dive or swim underwater as this increases the pressure of water. When your child is swimming in a well-maintained swimming pool, with adequate levels of chlorine, he or she shouldn’t need to wear earplugs, although it is OK to do so if preferred.

Dirty or soapy water may be more of a problem, and you should use earplugs when you wash your child’s hair or if bath time involves putting his or her head under the water. You can make your own waterproof earplugs by covering a small amount of cotton wool with petroleum jelly. You can also buy earplugs from your chemist or some audiology clinics. You will need to take these precautions until the grommets have fallen out. This usually takes between nine and 18 months.

Around one in 20 children develop an infection after a grommet operation. Infections after grommets aren’t usually painful and your child may not seem ill, but if you see a yellowish liquid coming out of your child’s ear, see your GP for advice. Your GP may prescribe antibiotic eardrops for your child to take or, if your child is more unwell, a course of antibiotics by mouth.

It’s safe for your child to fly after surgery for grommets. Having grommets put in helps air to move in and out of the ear more easily, which reduces stress on your child’s eardrum and makes changes in air pressure easier to cope with. This helps to prevent pain when the plane is climbing or when it’s coming down to land.

F urther information

-

National Deaf Children's Society

0808 800 8880

www.ndcs.org.uk

-

Deafness Research UK

0808 808 2222

www.deafnessresearch.org.uk

S ources

- Diagnosis and management of childhood otitis media in primary care. Section 1: Introduction. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). www.sign.ac.uk, accessed 5 September 2009

- Otitis media with effusion. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. www.cks.nhs.uk, accessed 5 September 2009

- Moore K, Dalley A. Clinically oriented anatomy. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 1999

- Glue ear. British Association of Otorhinolaryngologists – Head and Neck Surgeons. www.entuk.org, accessed 5 September 2009

- Toivonen M , Paakkonen R , Savolainen S, et al. Noise attenuation and proper insertion of earplugs into ear canals. Ann Occup Hyg 2002; 46:527-530

- Williamson I. OME in children. Clinical Evidence. www.clinicalevidence.bmj.com, accessed 5 September 2009

- Surgical management of otitis media with effusion in children. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. www.nice.org.uk, accessed 5 September 2009

- Perera R, Haynes J, Glasziou PP, et al. Autoinflation for hearing loss associated with otitis media with effusion. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 4. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006285

- Williamson I, Little P. Otitis media with effusion: the long and winding road? Arch Dis Child 2008; 93:268

- Simon C, Everitt H, Kendrick T. Oxford handbook of general practice. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006:926

Relat ed topics