Indigestion

Published by Bupa's Health Information Team, August 2010.

This factsheet is for people who have indigestion, or who would like information about it.

Indigestion (dyspepsia) is the term used to describe pain or discomfort in the upper abdomen or chest, generally occurring soon after meals.

About indigestion

Symptoms of indigestion

Causes of indigestion

Diagnosis of indigestion

Treatment of indigestion

About indigestion

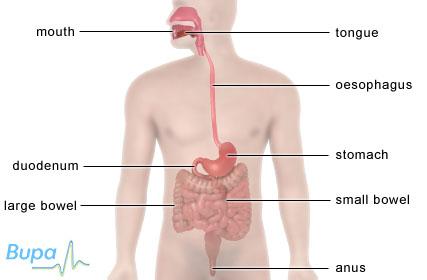

You get indigestion when the acid in your stomach flows back up your oesophagus (the pipe that goes from your mouth to your stomach) or when your stomach is irritated or inflamed. Although indigestion is most common after meals, you can get it at any time.

Heartburn is a burning pain caused by your stomach acid flowing back up your oesophagus (called reflux). This occurs if the valve (sphincter) at the top of your stomach doesn't work properly. The medical term for this condition is gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD).

Symptoms of indigestion

If you have indigestion you may have the following symptoms:

- pain, fullness or discomfort in the upper part of your abdomen or chest

- heartburn

- loss of appetite

- feeling sick

- flatulence (gas passed from your rectum), burping or belching

Depending on the cause of your indigestion, your symptoms may go very quickly, come and go, or they may be regular and last for a long time.

You should visit your GP for advice if you have:

- unexplained weight loss

- unexplained and continual symptoms of indigestion for the first time and you’re 55 or older

- severe pain, or if the pain gets worse or changes

- blood in your vomit, even if it's only specks of blood

Causes of indigestion

Your stomach produces a strong acid that helps you to digest food and protects you against infection. A layer of mucus lines your stomach, oesophagus and bowel to act as a barrier against this acid. If the mucous layer is damaged, your stomach acid can irritate the tissues underneath.

Lifestyle triggers

Some of the following can trigger symptoms of indigestion:

- drinking too much alcohol

- smoking

- stress and anxiety

- medicines, such as aspirin and anti-inflammatory medicines, used to treat arthritis

- eating certain foods, such as coffee and chocolate, can relax the sphincter at the join between your oesophagus and stomach or cause direct irritation to the lining of your oesophagus

Being overweight or obese can increase the pressure on your stomach and contribute to feelings of indigestion.

Underlying medical conditions

Some medical conditions can cause symptoms of indigestion and heartburn.

Peptic ulcers are ulcers in your stomach or the first part of your small bowel (duodenum). They occur when the lining of either your stomach or your duodenum is damaged and becomes inflamed. Peptic ulcers are usually caused by a bacterium called Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori). These bacteria live in the mucous layer of your stomach. Although they don’t always cause symptoms, they can cause peptic ulcers in some people.

Heartburn can be triggered by hiatus hernia. Hiatus hernia occurs when part of your stomach or sphincter slide up into your chest cavity, causing reflux.

Certain types of cancer can trigger the symptoms of indigestion, but this is rare.

Pregnancy

Many women suffer from indigestion during pregnancy. This may be triggered by high levels of the female hormones progesterone and oestrogen, which relax your sphincter.

Diagnosis of indigestion

Your GP will ask about your symptoms and examine you. He or she may also ask you about your medical history.

If lifestyle changes and medicines don't help to improve your symptoms, your GP may recommend further tests, such as those listed below.

- Breath tests or blood tests to detect the presence of H. pylori.

- A gastroscopy – a procedure used to look inside your oesophagus, stomach and your duodenum. During a gastroscopy your doctor may take a biopsy (a small sample of tissue). This will be sent to a laboratory for testing.

- A barium swallow and meal X-ray. This is a test that involves swallowing a drink containing barium (a substance that shows up on X-ray images). X-ray images of your abdomen then show the inside of your bowel more clearly.

Treatment of indigestion

Self-help

There are a few things you can do to reduce the symptoms of indigestion, including:

- losing excess weight

- cutting down on fatty foods, tea, coffee, alcohol and anything else that you think triggers your symptoms

- stopping smoking

- sleeping in a more upright position, propped up on a pillow (the action of gravity reduces reflux)

- eating more than three hours before going to bed if you have a peptic ulcer

- reducing your stress levels

- not eating too much or too quickly

Medicines

Over-the-counter medicines

You can buy a range of indigestion medicines from your pharmacist without a prescription. Always read the patient information that comes with your medicine and if you have any questions, ask your pharmacist for advice.

Antacids are medicines that can relieve symptoms of indigestion by neutralising acid in your stomach. They usually contain magnesium or aluminium.

Some medicines for indigestion contain an ingredient called an alginate, which forms a barrier that floats on top of your stomach contents to prevent reflux. Side-effects of antacids can include diarrhoea and constipation.

If antacids don't work, or if you need to take large quantities of antacid medicines to relieve your symptoms, your pharmacist may recommend H2 blockers. These work by reducing the amount of acid that your stomach produces. Examples of H2 blockers are famotidine and ranitidine.

If your symptoms continue after taking antacids or H2 blockers, your pharmacist may suggest that you try a low dose of another type of medicine called a proton pump inhibitor. Proton pump inhibitors work by stopping your stomach producing acid. You can take an over-the-counter proton pump inhibitor for a maximum of four weeks. Examples of these are omeprazole or lansoprazole.

Prescription-only medicines

If a proton pump inhibitor is controlling your symptoms, your GP can prescribe you one for long-term use.

If your symptoms continue after taking a proton pump inhibitor for two weeks, your GP can prescribe another type of medicine called a prokinetic. This works by making food pass more quickly through your stomach, so that you’re less likely to experience symptoms. Domperidone and metoclopramide are both prokinetics.

If you have an H. pylori infection, your GP may recommend having triple therapy to kill off the bacterial infection. This usually means taking a proton pump inhibitor combined with two different antibiotics, for seven days.

Always ask your doctor for advice and read the patient information leaflet that comes with your medicine.

Surgery

Surgery for indigestion or heartburn is rare. Your doctor will usually only recommend it if medicines don’t work or if you don’t want to take proton pump inhibitors for long periods of time.

If you have a hiatus hernia and your symptoms are severe, your GP may refer you to a surgeon. He or she may recommend that you have surgery to repair the hernia.

Talking therapies

Some people may find that talking therapies, such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and psychotherapy reduce the symptoms of indigestion.

This section contains answers to common questions about this topic. Questions have been suggested by health professionals, website feedback and requests via email.

Why is indigestion common in pregnancy?

My indigestion is caused by gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD). What does this mean and what can I do to help my condition?

I often feel bloated after eating and have a lot of wind, which I find embarrassing. What can I do about this?

Why is indigestion common in pregnancy?

Around eight in every 10 women are thought to suffer from indigestion (dyspepsia) during pregnancy. You may develop symptoms because your baby increases pressure against your stomach. This can increase your chance of acid reflux.

Explanation

One of the main symptoms of indigestion is heartburn. Heartburn is a burning pain caused by your stomach acid flowing back up your oesophagus (the pipe that goes from your mouth to your stomach). This is called reflux. The medical term for the condition is gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD).

Indigestion symptoms may start at any time during your pregnancy. They are usually more frequent or severe in the third trimester of your pregnancy.

It's important that you contact your GP for advice if you’re suffering from indigestion. He or she will want to rule out any other causes of your symptoms.

You may find that certain foods make your symptoms worse. Possible triggers include fruit juices, chocolate and fatty or spicy foods. Don't eat any foods that trigger your symptoms. Try keeping a diary of what you have eaten and when you get indigestion. This will help you identify which food or drink is causing the problem. Reducing your stress levels may also help reduce your symptoms.

Indigestion is often caused by your growing baby increasing the pressure against your stomach. It may also be caused by changes in your hormone levels, which relaxes the valve (sphincter) at the join between your oesophagus and stomach. Your symptoms should improve very quickly after your baby is born, once your hormones return to the levels they were at before you became pregnant.

Further information

CORE (Digestive Disorders Foundation)

www.corecharity.org.uk

Sources

- Dyspepsia (pregnancy-associated) – Background information. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. www.cks.nhs.uk, accessed 29 June 2010

- Gastroesophageal reflux (GERD). The Merck Manuals Online Medical Library. October 2006. www.merck.com, published October 2006

- Dyspepsia (pregnancy-associated) – Management: self-care and follow up. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. www.cks.nhs.uk, accessed 29 June 2010

- Dyspepsia (pregnancy-associated) – Background information: causes. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. www.cks.nhs.uk, accessed 29 June 2010

My indigestion is caused by gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD). What does this mean and what can I do to help my condition?

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) occurs when the contents of your stomach are brought back up into your oesophagus (the pipe that goes from your mouth to your stomach). When this happens, the acid in your stomach causes a burning sensation known as heartburn.

Explanation

If you have GORD, it’s likely that the valve at the join between your oesophagus and stomach doesn't work properly, allowing reflux of the stomach acid. Most reflux occurs after you have eaten.

You can buy several medicines over the counter from your pharmacist to help relieve your symptoms. These include antacids, which act by neutralising the acid in your stomach. Some medicines also contain an alginate, which forms a barrier that floats on top of your stomach contents to prevent reflux.

You can also make some lifestyle changes to help your symptoms. You may find that eating a large, rich meal late in the evening makes your symptoms worse, so you may wish to eat earlier or change some of the foods that you eat. Some foods bring on symptoms of heartburn every time they are eaten. These include coffee, alcohol and acidic drinks. Keeping a diary of what you have eaten and when you get heartburn can help you to identify which food is causing the problem.

Cutting down on how much alcohol you drink may also help to reduce your GORD symptoms. Alcohol is thought to increase how much acid your stomach produces.

Cigarette smoking has also been shown to increase symptoms of GORD. If you smoke, try to stop.

Further information

CORE (Digestive Disorders Foundation)

www.corecharity.org.uk

Sources

- Dyspepsia (proven gastro-oesophageal reflux disease) – Background information: gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. www.cks.nhs.uk, accessed 29 June 2010

- Dyspepsia (proven gastro-oesophageal reflux disease) – Background information: cause. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. www.cks.nhs.uk, accessed 29 June 2010

- Gastroesophageal reflux (GERD). The Merck Manuals Online Medical Library. October 2006. www.merck.com, published October 2006

- Joint Formulary Committee, British National Formulary. 59th ed. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, March 2010; 32–34.

- Dyspepsia: Managing dyspepsia in adults in primary care. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), August 2004. www.nice.org.uk

- Dyspepsia (proven gastro-oesophageal reflux disease) – Background information: risk factors. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. www.cks.nhs.uk, accessed 29 June 2010

I often feel bloated after eating and have a lot of wind, which I find embarrassing. What can I do about this?

A lot of people complain about having too much wind (gas), especially after eating. Normally, gas passes out through your rectum (called flatulence), or out through your mouth as belching. When gas doesn't pass out of your body easily, it can cause bloating and discomfort. Making some changes to your diet can help to ease your symptoms.

Explanation

Every time you swallow, you take air into your stomach. Eating or drinking quickly, chewing gum and smoking all add to the amount of air you swallow. If you’re under a lot of stress, you may swallow a lot of air without even noticing it. Therefore stopping smoking, reducing your stress levels and eating and drinking more slowly can help relieve your symptoms.

Reducing the amount of fizzy drinks you drink can help as they cause your stomach to produce more gas. Certain foods such as beans and cabbage can also increase the amount of gas you produce. When these foods are broken down by bacteria in your large bowel, they form gas.

If you have lactose intolerance, your stomach and small bowel can't break down a sugar called lactose which is found in cows', goats' and sheeps' milk. As a result, lactose enters your large bowel where again, the bacteria break it down and this produces large amounts of gas. Your GP can carry out a test to see if you can break down lactose. If you have lactose intolerance, your GP may advise you to reduce the amount of milk you drink.

If your symptoms aren't reduced by changes in your diet or if they worsen, contact your GP for advice.

Further information

CORE (Digestive Disorders Foundation)

www.corecharity.org.uk

Food Standards Agency

www.food.gov.uk

Sources

- Symptoms: Symptoms and Diagnosis of Digestive disorders. The Merck Manuals Online Medical Library. www.merck.com/mmhe, published May 2007

- Lactose intolerance. The Merck Manuals Online Medical Library. www.merck.com.mmhe, published December 2007

Related topics

Diabetes – insulin-dependent (type 1)

Diabetes – non-insulin-dependent (type 2)

Giving up smoking

Hiatus hernia

Lactose intolerance

Pregnancy health

Stress

Treatments for indigestion

This information was published by Bupa's Health Information Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been peer reviewed by Bupa doctors. The content is intended for general information only and doesn’t replace the need for personal advice from a qualified health professional.

Publication date: August 2010.

Indigestion factsheet

Visit the indigestion health factsheet for more information.

Related topics

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

Gastroscopy

Giving up smoking

Indigestion medicines

Hiatus hernia

MRI scan

Pelvic and abdominal ultrasound

Peptic ulcer

Stress

Treatments for indigestion

Further information

CORE (Digestive Disorders Foundation)

www.corecharity.org.uk

Sources

- Dyspepsia: Managing dyspepsia in adults in primary care. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), August 2004. www.nice.org.uk

- Symptoms: Symptoms and Diagnosis of Digestive disorders. The Merck Manuals Online Medical Library. www.merck.com/mmhe, published May 2007

- Dyspepsia (unidentified cause) – Background information. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. www.cks.nhs.uk, accessed 29 June 2010

- Dyspepsia (proven gastro-oesophageal reflux disease) – Background information. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. www.cks.nhs.uk, accessed 29 June 2010

- Gastroesophageal reflux (GERD). The Merck Manuals Online Medical Library. www.merck.com, published October 2006

- Dyspepsia (proven gastro-oesophageal reflux disease) – Management: general measures to reduce symptoms. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. www.cks.nhs.uk, accessed 29 June 2010

- Joint Formulary Committee, British National Formulary. 59th ed. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, March 2010; 42–44, 47

- Practice guidance: OTC omeprazole. Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. www.rpsgb.org, published September 2006

This information was published by Bupa's Health Information Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been peer reviewed by Bupa doctors. The content is intended for general information only and doesn’t replace the need for personal advice from a qualified health professional.

Publication date: August 2010.