Long-sightedness

Published by Bupa's Health Information Team, May 2010.

This factsheet is for people who have long-sightedness, or who would like information about it.

Long-sightedness is a common vision problem, which means that people can't focus on close objects so they look blurred. Long-sightedness is known medically as hyperopia or hypermetropia. Another name for it is far-sightedness.

About long-sightedness

Symptoms of long-sightedness

Causes of long-sightedness

Diagnosis of long-sightedness

Treatment of long-sightedness

About long-sightedness

Normal vision

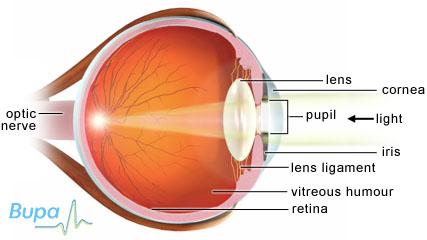

When you look at something, light rays from the object pass into your eye through your cornea (the clear dome that covers your pupil) then through your lens and on towards the retina at the back of your eye. In a healthy eye, your lens and cornea focus the light rays on a small area of your retina so that you can see the object clearly.

The lens of your eye is naturally dome-shaped and very flexible. This allows you to focus from a range of distances, on objects far away and those that are very close up.

To focus on near objects, the ciliary muscles at either side of your lens tighten causing it to change shape. Your lens becomes thicker and more curved, bringing light rays and close objects into sharp focus on your retina. This is called accommodation. To focus on objects in the distance, your lens returns to its natural resting state.

What is long-sightedness?

Long-sightedness is a refractive error. This means there is an error in the way that your eye focuses light rays.

If you’re long-sighted, light rays are focused behind your retina. This may be because your eyeball is too short, your cornea isn’t curved enough or your lens isn’t thick enough. You may find that close objects seem fuzzy or blurred. Distant objects won't look blurred because the light rays don’t need as much focusing power, so they focus on your retina properly.

Long-sightedness often starts in childhood.

Age-related long-sightedness

As you get older, your lenses naturally lose their flexibility, becoming stiffer and less elastic. This reduces the power of accommodation, and eventually light rays from near objects no longer focus on your retina.

Age-related long-sightedness is known medically as presbyopia. Presbyopia isn’t a disease – it’s a result of the normal, expected changes that happen to your eyes as you get older. Almost everyone will develop age-related long-sightedness, regardless of whether you already wear glasses or contact lenses or not.

Symptoms of long-sightedness

Symptoms of long-sightedness are:

- close objects appear fuzzy or blurry, while distant objects remain in focus

- headaches

- tired eyes

If you have presbyopia, you may also have double vision and if you’re short-sighted you may need to take your glasses off to read. Some people with presbyopia find that they need brighter lighting when they are reading.

A symptom of long-sightedness in children is a squint, where one eye points inwards more than the other. If a squint isn’t treated in a baby or young child, it can lead to permanent vision problems, such as a ‘lazy eye’. If you think your child has a squint, it's important to contact his or her GP for advice.

Causes of long-sightedness

You’re more likely to develop long-sightedness if other people in your family have it.

A common cause of long-sightedness is ageing (in which case, it’s called presbyopia). Changes to the lens in your eye typically begin around the age of 40 and are completed by the time you are 60. You may be at risk of developing presbyopia at a younger age (premature presbyopia) if you have a job that requires you to do close-up work.

Diagnosis of long-sightedness

If you can see far away objects more clearly than near objects, you should visit an optometrist (a registered health professional who examines eyes, tests sight and dispenses glasses and contact lenses) to have your eyes tested.

It's important to have regular eye tests. As well as diagnosing any vision problems, they can reveal other serious illnesses, such as diabetes and high blood pressure. The College of Optometrists advise that you should have an eye test at least every two years, although some people need them more often – ask your optometrist or GP for more advice.

Treatment of long-sightedness

Glasses and contact lenses

Long-sightedness can usually be corrected by you wearing glasses or contact lenses. A convex lens – in a pair of glasses or contact lenses – refocuses light rays onto your retina, returning your vision to normal.

Your optometrist will discuss with you what options are available.

Glasses are usually recommended for children. They may also be more suitable for older people than contact lenses.

Wearing contact lenses can increase your risk of getting an eye infection. You can reduce your risk by making sure you follow all the advice of your contact lens practitioner.

If you develop presbyopia and already wear glasses, you may be prescribed bifocal or varifocal (progressive) lenses. These lenses are of different strengths in different parts of the lens. If you already wear contact lenses, you may be prescribed bifocal contact lenses or reading glasses (as well as your contact lenses). It's important to have check-ups with your optometrist every two years. This will help to make sure that your glasses or contact lenses stay the correct strength for you.

Surgery

Laser refractive surgery

A laser can be used to make alterations to your cornea, so that light rays are correctly focused onto your retina. The operation is carried out under local anaesthesia, so you're awake throughout. It only takes a few minutes.

There are various types of laser refractive surgery, which differ according to how your surgeon gains access to your cornea. These include PRK (photorefractive keratectomy), LASEK (laser epithelial keratomileusis) and LASIK (laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis). Laser refractive surgery isn't suitable for everyone, and you will need to talk to an ophthalmic surgeon to find out if it's right for you. Laser surgery can’t be used to treat presbyopia.

Depending on the exact procedure you have, your vision may take anything from one week to several months to improve.

Lens replacement surgery

Lens replacement surgery called presbyopic lens exchange (PRELEX) can be used to treat presbyopia. This is an operation to replace the lens in your eye with an artificial one. This type of operation is usually performed under local anaesthesia. This blocks pain from your eye and you will stay awake during the operation.

Scleral expansion surgery

Scleral expansion surgery is a procedure that has been used in the past to treat presbyopia. It involves your surgeon making small incisions in your eye and inserting bands to stretch the part of your eye that controls focusing.

However, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has recommended that this procedure should no longer be used as it hasn’t proven to be effective and there are potential risks involved.

Published by Bupa's Health Information Team, May 2010.

This section contains answers to common questions about this topic. Questions have been suggested by health professionals, website feedback and requests via email.

My child has a squint because of long-sightedness. What can be done about it?

How will I know if I have presbyopia?

How can I prevent presbyopia?

My child has a squint because of long-sightedness. What can be done about it?

The two main treatments for a squint caused by long-sightedness are wearing glasses and wearing an eye patch.

Explanation

Around five in every 100 children develop a squint and most of these are caused by long-sightedness.

Children can see things that are very close up because the lenses in their eyes have more focusing power. If your child is long-sighted, it means he or she has problems seeing things that are close up, so he or she needs to focus even harder. Over-focusing can cause blurred vision and make your child’s eyes turn inwards. To stop this happening, your child’s brain can switch off the sight in one eye. When this happens, his or her eye will tend to turn inwards – this is how most squints develop. This can also lead to what is called a 'lazy eye', where sight doesn't develop properly in your child’s eye with the squint. If this isn’t corrected, it can lead to permanent sight loss. If you think your child has a squint, don't ignore it. Speak to your GP, health visitor or your child’s school nurse for advice.

The two main treatments for a squint caused by long-sightedness are wearing glasses and wearing an eye patch. If a squint is picked up early on and treated, most children will eventually have good sight in both eyes. However, if a squint isn't picked up until after the age of about seven, a lack of treatment can have a permanent effect on a child’s sight.

If your child has a squint, it's very likely that he or she will need to wear glasses. Your child will need to wear them all the time, which can sometimes be difficult. Some children say they can see better without the glasses – this is because their eyes have become used to over-focusing without them. In time, if your child keeps wearing the glasses, his or her eyes will learn to relax and let the glasses focus for them. Most children don’t need anything more than glasses to correct their squint.

If your child has a lazy eye, he or she will usually need to wear a patch over the good eye (called patching or occlusion). This makes the lazy eye work harder to focus and in time will improve the sight in that eye. Your child will wear the patch under his or her glasses.

Your child may be offered surgery to correct his or her squint, if other treatment methods such as wearing glasses or an eye patch haven’t worked.

Further information

Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB)

0303 123 9999

www.rnib.org.uk

Sources

- Squint in childhood. Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB). www.rnib.org.uk, accessed 25 January 2010

- Squint. The College of Optometrists. www.college-optometrists.org, accessed 25 January 2010

- Lazy eye (amblyopia). British and Irish Orthoptic Society. www.orthoptics.org.uk, accessed 25 January 2010

- Squint. British and Irish Orthoptic Society. www.orthoptics.org.uk, accessed 25 January 2010

How will I know if I have presbyopia?

The main symptom of presbyopia is having difficulty seeing things close up.

Explanation

Presbyopia is also known as age-related long-sightedness. As you get older, your lenses slowly lose their flexibility, becoming stiffer and less elastic. Eventually, light rays from near objects no longer focus on your retina and you become long-sighted. It happens to almost everyone, regardless of whether you already wear glasses or contact lenses or not.

Usually, you won’t begin to have symptoms of presbyopia until you’re in or approaching your 40s. Symptoms may only become noticeable when you’re carrying out certain tasks.

Difficulty reading is a sign of presbyopia. You may find you need to hold reading materials at arm’s length as you have blurred vision at normal reading distance. You may become tired when reading or need more light to read. Any close work such as threading a needle or seeing fine detail on an object will also become harder and may give you headaches. This may be especially noticeable at the end of a busy day or if you’re tired at the end of the working week. If you have short-sightedness (myopia), you may find that you rely less on your glasses, taking them off more often.

As presbyopia is an age-related condition, it's recommended that you have your eyes tested by an optometrist once you’re over 40.

The symptoms of presbyopia will gradually get worse between the ages of 40 and 60. It's important to see your optometrist regularly as the lenses in your glasses or contact lenses may no longer be strong enough for you. It's recommended that you have an eye test every two years. You will be able to discuss any changes to your vision and any concerns you have.

Your optometrist won't just check your vision; he or she will also check your eyes for any signs of disease or general health problems. This type of check-up can pick up early signs of conditions such as glaucoma which, if left untreated, can lead to loss of vision and blindness.

Further information

The College of Optometrists

www.college-optometrists.org

Sources

- Presbyopia. The Eyecare Trust. www.eyecaretrust.org.uk, accessed 25 January 2010

- Eyesight problems. The College of Optometrists. www.college-optometrists.org, accessed 25 January 2010

- Having an eye test. Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB). www.rnib.org.uk, accessed 25 January 2010

- 10 reasons for having an eye examination. The College of Optometrists. www.college-optometrists.org, accessed 25 January 2010

How can I prevent presbyopia?

You can't prevent presbyopia as it's a natural part of the ageing process. Almost everyone will develop presbyopia eventually.

Explanation

Presbyopia isn't a disease – it's a normal expected change that happens to almost everyone sooner or later. The lens of your eye begins to stiffen and lose elasticity around the age of 40 – these changes are usually completed by the time you’re 60. There is nothing you can do to prevent these changes from happening.

Further information

The College of Optometrists

www.college-optometrists.org

Sources

- Presbyopia. The Eyecare Trust. www.eyecaretrust.org.uk, accessed 25 January 2010

- Care of the patient with presbyopia. American Optometric Association. www.aoa.org, accessed 25 January 2010

Related topics

Long-sightedness

LASIK (laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis)

Short-sightedness

Glaucoma

Healthy eating

This information was published by Bupa's Health Information Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been peer reviewed by Bupa doctors. The content is intended for general information only and does not replace the need for personal advice from a qualified health professional.

Publication date: May 2010.

Long-sightedness factsheet

Visit the long-sightedness health factsheet for more information.

Related topics

High blood pressure

LASIK (laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis)

Local anaesthesia and sedation

Short-sightedness

Type 1 diabetes

Type 2 diabetes

Further information

Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB)

0303 123 9999

www.rnib.org.uk

The College of Optometrists

www.college-optometrists.org

Sources

- Refractive errors (glasses). British and Irish Orthoptic Society. www.orthoptics.org.uk, accessed 25 January 2010

- Farsightedness. The Eyecare Trust. www.eyecaretrust.org.uk, accessed 25 January 2010

- How the eye works. Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB). www.rnib.org.uk, accessed 25 January 2010

- Presbyopia. The Eyecare Trust. www.eyecaretrust.org.uk, accessed 25 January 2010

- Squint. The College of Optometrists. www.college-optometrists.org, accessed 25 January 2010

- Eyesight problems. The College of Optometrists. www.college-optometrists.org, accessed 25 January 2010

- Care of the patient with presbyopia. American Optometric Association. www.aoa.org, accessed 25 January 2010

- 10 reasons for having an eye examination. The College of Optometrists. www.college-optometrists.org, accessed 25 January 2010

- Contact lenses. The Eyecare Trust. www.eyecaretrust.org.uk, accessed 25 January 2010

- Your child’s eyesight. The Eyecare Trust. www.eyecaretrust.org.uk, accessed 25 January 2010

- Types of lenses and coatings. The College of Optometrists. www.college-optometrists.org, accessed 25 January 2010

- Contact lens types. The Eyecare Trust. www.eyecaretrust.org.uk, accessed 25 January 2010

- A patients' guide to excimer laser refractive surgery. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. www.rcophth.ac.uk, published March 2006

- Laser refractive surgery. The College of Optometrists. www.college-optometrists.org, accessed 25 January 2010

- Photorefractive (laser) surgery for the correction of refractive errors. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), March 2006. www.nice.org.uk

- Corneal modifications for improved vision. The Eyecare Trust. www.eyecaretrust.org.uk, accessed 25 January 2010

- Lens implants: intra-ocular and clear lens replacement. The Eyecare Trust. www.eyecaretrust.org.uk, accessed 25 January 2010

- Scleral expansion surgery for presbyopia. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), July 2004. www.nice.org.uk

This information was published by Bupa's Health Information Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been peer reviewed by Bupa doctors. The content is intended for general information only and does not replace the need for personal advice from a qualified health professional.

Publication date: May 2010.