Scoliosis

Scoliosis is a sideways curve of the spine and has several different causes.

About scoliosis

Symptoms of scoliosis

Causes of scoliosis

Animation – How idiopathic scoliosis occurs

Diagnosis of scoliosis

Treatment of scoliosis

Prevention of scoliosis

Living with scoliosis

About scoliosis

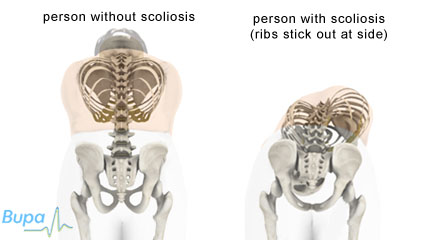

It’s normal to have a slight sideways curvature in your spine. Scoliosis is defined as a curve of more than 10 degrees. The curvature can be a C-shape or S-shape, and the spine may also be rotated (twisted).

There are two types of scoliosis. Non-structural (mobile) scoliosis is usually caused by a condition outside the spine and disappears when that is corrected. For example, if one of your legs is longer than the other, the curvature in your spine will disappear when you sit down.

Structural (true) scoliosis is a fixed curvature in your spine. Usually the underlying cause of structural scoliosis can't be treated.

Symptoms of scoliosis

Scoliosis usually has no symptoms unless the curvature becomes severe. It's not usually painful but because of the changes in appearance, it can be a distressing condition.

The first sign of scoliosis may be that clothes seem to hang unevenly, or when a parent or teacher notices a change in posture. Other signs may include one shoulder being higher than the other, or one shoulder blade sticking out. The space between the body and the arms may look different on each side when your child stands with their arms at their sides. One hip may be more prominent. A curvature can develop rapidly in children during growth spurts. A small curve may become a larger curve over a relatively short period.

If the curve is in the upper back, the ribs may stick out on one side. This is known as a rib hump. In older girls and women, one breast may be higher than the other or appear larger than the other.

Causes of scoliosis

There are a number of causes of scoliosis.

Idiopathic

Idiopathic scoliosis is a type of acquired scoliosis – that is one not present at birth. ‘Idiopathic’ means an illness of unknown cause. The curvature with idiopathic scoliosis is almost always to the right.

Idiopathic scoliosis is quite common, affecting two to three in every 100 people. In eight out of ten cases, the condition usually develops between the ages of 10 and 15, during the growth spurt of puberty. This is called late onset or adolescent idiopathic scoliosis and the curve is almost always to the right. During adolescence, girls are much more likely to be affected. This is probably because girls typically have shorter and faster growth spurts than boys.

Less commonly, scoliosis develops in younger children. This is called early onset idiopathic scoliosis. The curvature is usually to the left, and slightly more boys are affected than girls.

Idiopathic scoliosis often seems to run in families. About three out of 10 people with scoliosis have one or more close family members with the same condition.

Idiopathic scoliosis is a type of structural scoliosis or true scoliosis, which means that usually the underlying cause of scoliosis can't be reversed.

How idiopathic scoliosis occurs

http://hcd2.bupa.co.uk/fact_sheets/html/scoliosis.html

Congenital

If you’re born with an abnormally curved spine, it’s called congenital scoliosis. The cause of this is development of the vertebrae that is not symmetrical. Sometimes two vertebrae are fused (joined together) on one side and as the person grows the spine becomes curved. The curve is usually obvious before the child reaches adolescence.

Neuromuscular

This is due to a condition that affects the nerves or muscles of the back, such as cerebral palsy or muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscular scoliosis is to be of the ‘structural’ type when there is rotation as well as curve of the spine and ‘non-structural’ if there is no rotation of the spine. Non structural scoliosis can be due to problems including:

- poor posture

- muscle spasm eg caused by a compressed or ‘slipped’ disc

- having one leg shorter than the other

Correcting the underlying problem can reverse this type of scoliosis.

Other causes of scoliosis include damage or uneven growth of the spine caused by trauma and infection caused by tuberculosis of the spine.

The effects of scoliosis

Diagnosis of scoliosis

Visit your GP if you’re concerned about scoliosis. He or she will ask about your symptoms and will perform an examination. Your GP will ask you to bend forward from the waist, with the palms of your hands together. Your ribs will stick up more on one side and cause a bulge in your back if you have scoliosis.

Your GP may ask you about your medical history and also ask you about other family members. If your GP thinks you have scoliosis, then he or she will usually refer you to a specialist. This is often an orthopaedic surgeon with a specialist interest in spinal deformity.

Your GP may refer you to have X-rays of your back to show the position and size of the curvature. The curve is given a measurement in degrees, called the Cobb angle. The radiologist or surgeon can compare early X-rays with later ones to tell whether the curvature is stable or getting more pronounced.

Sometimes you will have other tests such as a CT or MRI scan. A CT (computerised axial tomography) scan uses multiple X-ray pictures to make detailed cross-sectional images of the body. An MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan is similar, but it uses magnets and radiowaves. CT and MRI images can be processed by computer software to make 3-D images and give your doctors precise information about, for instance, the alignment of spinal bones.

Most cases of scoliosis are mild and you will just need regular check-ups to monitor the curvature. These check-ups will probably be every four to six months.

Only one in 10 people need to have treatment for their scoliosis. In general, the younger a child is when the scoliosis is apparent the more chance the curve will need treatment.

At present there is no national screening programme for scoliosis.

Treatment of scoliosis

Bracing

Your doctor may recommend a back brace to children if the spinal curve is more than around 20 degrees. You should discuss this treatment option thoroughly with your doctor. A brace only works for children who have not finished growing. It will not correct scoliosis, but can help to stop the curvature getting worse. Different types of brace are available, usually made out of a rigid plastic or fibreglass. The most common type covers roughly the same area as a waistcoat. For more marked curvature, a brace that extends higher up the body and under the chin may be required. To be effective, a brace needs to be worn for up to 23 hours a day.

The medical evidence for how well braces work is mixed, but they’re likely to be more effective when treatment is started younger, while the back is still growing. Braces are usually worn until the child stops growing.

Children may feel embarrassed and might find wearing a brace difficult and uncomfortable at first. Family support is crucial, and there are also support groups you can get in touch with (see Further information). Talking to other children or teenagers who are going through the same thing may help.

Surgery

Depending on the degree of curvature, your specialist may recommend surgery. Surgery aims to reduce the amount of curvature of the spine and prevent it from getting worse.

The most common technique is spinal fusion, in which the affected bones of the spine are straightened and then fused (joined) together. The curvature is largely corrected by metal rods and screws fitted to the spine.

Surgery to correct scoliosis can involve a long and complex operation with a small risk of damage to the spinal cord. In order to make a well-informed decision and give your consent for the operation, you need to be aware of the possible side-effects and the risk of complications. Your surgeon will discuss these with you.

Other treatments

Other treatments for scoliosis include exercises and electrical stimulation. There is little medical evidence to say that these are effective.

Prevention of scoliosis

There is no way to prevent idiopathic scoliosis. Early detection and treatment, if necessary, helps to prevent it getting worse.

If you have a history of scoliosis in your family, children can be checked regularly for scoliosis from the age of nine throughout their teens. All newborn children are checked for the rare early onset type as part of a routine postnatal check-up.

Living with scoliosis

For most people who develop idiopathic scoliosis as adolescents, it doesn’t cause any life-threatening problems, but it can make life difficult. As the curvature gets worse, the spinal bones (vertebrae) tend to rotate. This rotates the ribs, reducing the space in the rib cage and making it harder to breathe properly. This is only a problem for severe curvature, over 60 degrees.

Severe curvature can also restrict movement. The earlier scoliosis begins and the higher up the back the curve is, the worse the curvature.

Scoliosis won't cause major physical complications, but having spinal curvature can affect your body image and confidence.

Even untreated, there is good evidence that people lead full and productive lives.

This section contains answers to common questions about this topic. Questions have been suggested by health professionals, website feedback and requests via email.

Will my scoliosis stay the same or get worse?

Will scoliosis stop my child playing sport?

Does surgery for scoliosis carry any risks?

Will my scoliosis stay the same or get worse?

About two-thirds of people who are diagnosed with scoliosis while they are still growing will have curves that increase in size (progress).

Explanation

Your sex, size and type of the curve you have, and the amount of growing you have left to do are important factors for predicting how your scoliosis will progress. It’s not possible to give concrete predictions for individuals, however it’s important that you visit your GP or specialist if you’re worried about your curve increasing in size :

In growing children and adolescents mild curvatures can worsen quite quickly. Therefore it’s important that children have frequent check-ups with their GP.

Will scoliosis stop my child playing sport?

Not necessarily. Many people diagnosed with scoliosis are able to play sport and do exercise.

Explanation

Exercise is good for children. It stimulates muscle and bone development and helps keep hearts healthy. What your child is able to do will depend on factors such as the treatment he or she has undergone, the degree of curvature of the spine and their general health. Scoliosis isn’t a weakness of the spine, but if severe it can affect breathing or cause backache. If your child has mild scoliosis, he or she should try and lead a normal life, including taking part in sporting activities. If your child has a back brace, your doctor may advise him or her to take it off during contact sports. Talk to your doctor for more advice about any activities your child shouldn’t do.

Some specific back exercises have also been tried as a treatment for scoliosis but there is no evidence that they are effective.

Does surgery for scoliosis carry any risks?

All types of surgery carry some risks. Your child’s doctor will only recommend surgery for scoliosis if it’s considered that the benefits outweigh the risks. The risks depend on the type of procedure your child has, and his or her personal circumstances.

Explanation

Severe scoliosis is sometimes treated with a type of surgery called spinal fusion. Spinal fusion helps reduce the curvature of the spine and stops it from getting worse. In spinal fusion, several bones in the spine (vertebrae) are fused and two metal rods are attached to keep the spine straight.

Surgery for scoliosis is usually only carried out if it is severe and is getting worse. Like all surgery there are some risks involved. Some problems specific to spinal fusion are listed below.

- There is a small risk of spinal cord or nerve damage with any spinal surgery.

- Pseudoarthrosis. This is when the spine fails to properly fuse. It can happen years after surgery, and means your child may need another operation.

- Sometimes the rods attached to the spine may break or come loose. Another operation may be needed to correct this.

- Some people feel pain in their back following surgery. The cause isn’t always known, but further surgery can sometimes help.

- There is a chance of developing an infection – this can happen months or even years after surgery.

Talk to a doctor who specialises in spinal surgery for more advice about whether spinal fusion for scoliosis is the right choice for you or your child.

Further information

-

The Scoliosis Association UK

020 8964 5343

www.sauk.org.uk - Scoliosis Research Society

Sources

- Fairbank J. Spinal disorders. In: Bulstrode C, Buckwalter J, Carr A (Editors). Oxford Textbook of orthopedics and trauma. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002

- Simon C, Everitt H, Kendrick T. Oxford Handbook of General Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2 ed 2005: 871

- Scoliosis clinical features. GP Notebook. www.gpnotebook.co.uk, accessed 1 November 2009

- Scoliosis information. Scoliosis Association UK. www.sauk.org.uk, accessed 1 November 2009

- Effect of Bracing and Other Conservative Interventions in the Treatment of Idiopathic Scoliosis in Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials. Physical Therapy, 2005. 85:12; 1329-1339

- Searching for the genes that cause adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Scoliosis Association UK, accessed 29 October 2009

- Postural scoliosis. GP Notebook. www.gpnotebook.co.uk, accessed 29 October 2009

- Sciatic scoliosis. GP Notebook. www.gpnotebook.co.uk, accessed 29 October 2009

- Compensatory scoliosis. GP Notebook. www.gpnotebook.co.uk, accessed 29 October 2009

- Mobile scoliosis. GP Notebook. www.gpnotebook.co.uk, accessed 29 October 2009

- British Orthopaedic Association. The management of spinal deformity in the UK: A guide to good practice. British Orthopaedic Association. 2003 p.5

- Detection. Scoliosis Association UK. www.sauk.org.uk, accessed 1 November 2009

- Lenssinck ML, Frijlink AC, Berger MY et al. Effect of bracing and other conservative interventions in the treatment of idiopathic scoliosis in adolescents: a systematic review of clinical trials. Physical Therapy 2005;85:1329-1339

- Bunnell, WP. Selective screening for scoliosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2005;435:40-45

- National Screening Committee. UK NSC Database. www.screening.nhs.uk

- Detection. Scoliosis Association UK. www.sauk.org.uk, accessed 1 November 2009

- Rowe D, Bernstein S, Riddick M, et al. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of non-operative treatments for idiopathic scoliosis. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 1997:79-A(5): 664-674.

- Bracing. Scoliosis Association UK. www.sauk.org.uk, accessed 1 November 2009

- British Orthopaedic Association. The management of spinal deformity in the UK: A guide to good practice. British Orthopaedic Association. 2003

- Negrini S, Antonini G, Carabalona R, Minozzi S. Physical exercises as a treatment for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a systematic review. Pediatric Rehabilitation 2003; 6: 227-235

- Weinstein S, Dolan L, Spratt K, et al. Health and function of patients with untreated idiopathic scoliosis A 50-Year Natural History Study. JAMA 2003; 289: 559-566

Related topics

- Scoliosis

- Physical activity

- Osteoporosis