Stress incontinence

This factsheet is for people who have stress incontinence, or who would like information about it.

Urinary incontinence is the unintentional leaking of urine. Stress incontinence is when you suddenly leak urine because of an increase of pressure on your bladder. This could be from sneezing, coughing or lifting something heavy.

About stress incontinence

Symptoms of stress incontinence

Causes of stress incontinence

Diagnosis of stress incontinence

Treatment of stress incontinence

About stress incontinence

Stress incontinence is often referred to as bladder weakness or weak bladder. It's the most common type of urinary incontinence – about 200 million people worldwide have urinary incontinence – almost half will have stress incontinence. It can affect women and men of any ages but it's more common among women.

Other types of urinary incontinence include the following.

- Urge incontinence – this is when you have a sudden and intense urge to pass urine that is usually followed by an unintentional leakage of urine.

- Mixed urinary incontinence – when you unintentionally pass urine because of both stress and urge incontinence.

- Overflow incontinence (also known as chronic urinary retention) – this happens when your bladder doesn't empty properly, causing urine in it to spill out. It can be caused by weak bladder muscles or a blocked urethra (the tube that carries urine from your bladder out of your body). Overflow incontinence is rare in women.

Some people with severe stress incontinence have constant urine loss (also known as total incontinence). This usually occurs because the urethral sphincter (a group of muscles that surrounds your urethra and keeps urine in your bladder) doesn't close properly.

Symptoms of stress incontinence

If you have stress incontinence, small amounts of urine leak from your bladder when it's under sudden, unexpected pressure. This can be from laughing, coughing, sneezing, walking, exercising, lifting a heavy object or from changing position, for example, sitting to standing. Carrying out any movement that suddenly increases the pressure on your bladder can cause uncontrollable loss of small amounts of urine.

If you have any of these symptoms, see a doctor.

Causes of stress incontinence

Stress incontinence usually develops when the muscles in the pelvic floor or urethral sphincter have been damaged or weakened.

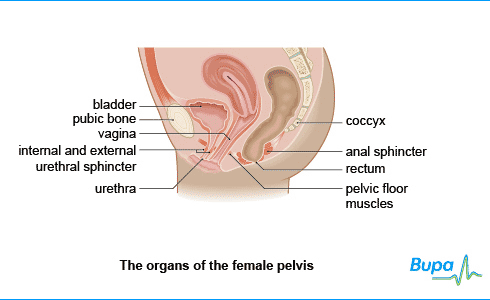

Your pelvic floor is made up of layers of muscles that form a sling passing from your coccyx (tip of your spine) to your pubic bone. It supports the bladder, bowel and uterus (womb), and forms the floor of the pelvis. Both men and women have a pelvic floor.

There are a number of factors that make you more likely to develop stress incontinence. For women, these can include the following.

- Pregnancy. Your pelvic floor or urethral sphincter can be weakened because of the extra weight and hormonal changes.

- Childbirth, especially if it takes a long time, your baby is large or you need to have forceps or a ventouse (a type of vacuum pump) during the birth.

- Muscle tearing during childbirth or episiotomies (where the muscle is cut to allow an easier birth).

- The menopause. If you're postmenopausal, you will have less oestrogen in your body, which can weaken your pelvic floor and urethral sphincter. The urethra shortens and its lining becomes thinner as the level of oestrogen declines during menopause. These changes reduce the urethral sphincter's ability to close tightly.

- A hysterectomy or other bladder operations can damage your muscles.

Men can develop stress incontinence as a result of prostate surgery. The urethral sphincter is close to the top of the prostate and may be slightly injured when the prostate is removed.

Other factors that increase the likelihood of developing stress incontinence in both men and women include:

- being constipated for a long time

- having a persistent cough

- age – your muscles weaken as you get older

- being overweight or obese – extra weight increases the pressure on your bladder and pelvic tissues

Diagnosis of stress incontinence

To diagnose stress incontinence, your doctor will first ask you about your symptoms and medical history. He or she may ask you to keep a 'bladder diary' for at least three days. This involves recording how much you drink, when you pass urine, the amount of urine you produce, whether you had an urge to urinate and the number of times you unintentionally leak.

Your doctor will usually do a test on a sample of your urine to check that your incontinence isn't being caused by an infection in your urinary tract – this consists of your kidneys, two ureters (the tubes that connect each kidney to your bladder), your bladder and your urethra. He or she may also do a blood test to check that your kidneys are working properly.

Your doctor may examine you. He or she might simply check for loss of urine while you cough or strain. A rectal (back passage) examination will check if you're constipated or whether the nerves to your bladder are damaged. In men, a rectal examination will determine if the prostate is enlarged. If you're a woman, your doctor will check for weakness of your pelvic floor and look for a prolapse – this is when organs near your vagina, such as your womb, bowel or bladder, slip down from their normal position.

You may be referred to a urologist (a doctor who specialises in identifying and treating conditions that affect the urinary system) or, if you're a woman, a gynaecologist (a doctor who specialises in women's reproductive health) or urogynaecologist (a doctor who focuses on urinary and associated pelvic problems in women).

Other tests for stress incontinence include the following.

- Ultrasound. This uses sound waves to produce an image of the kidneys, bladder and urethra. It's most commonly used to check that your bladder is emptying properly.

- Cystoscopy. A procedure used to look inside your bladder and urinary system using a flexible viewing tube. This can identify abnormalities that may be causing the incontinence.

- Urodynamic testing. These techniques measure the pressure in your bladder and the flow of urine. A thin, flexible tube, called a catheter, is inserted into your bladder through your urethra. Water is then passed through the catheter and the pressure in your bladder is recorded.

Please note that availability and use of specific tests may vary from country to country.

Treatment of stress incontinence

Self-help

There are several ways you can help yourself if you have been diagnosed with stress incontinence.

Being overweight or obese can make your stress incontinence worse because there is extra pressure on your pelvic floor muscles.

Exercising and eating healthily can help you to lose excess weight. The World Health Organization recommends doing 150 minutes (two and a half hours) of moderate exercise over a week. You can do this by carrying out 30 minutes on at least five days each week. Do low-impact exercises, such as walking or swimming.

High-impact exercise, such as running or sports involving jumping, can increase the pressure on your bladder and cause you to leak.

Drink enough fluid. Cutting down the amount you drink makes your urine more concentrated and it's likely to make your stress incontinence worse. Try to drink six to eight glasses of fluid regularly throughout the day. Passing urine frequently to prevent having a full bladder can also help.

Other things you can do to help yourself include the following.

- Brace your pelvic floor before you laugh, cough or sneeze – to do this, imagine that you're trying to stop your urine flow.

- Try not to have too much caffeine – caffeine is a diuretic (which causes your body to lose water by increasing the amount of urine your kidneys produce) and a bladder stimulant, meaning that it can cause you to need to urinate suddenly.

- Wear absorbent pads to absorb any leaks – you can buy these from drugstores (pharmacies) and some supermarkets.

Physical therapies

Your doctor will usually ask you to do pelvic floor muscle exercises (Kegel exercises). These exercises, if done correctly, strengthen your urethral sphincter and pelvic floor muscles to help you control urinating. To do pelvic floor muscle exercises, squeeze the muscles you would use to stop urinating and hold for a count of three. Your doctor will recommend that you do these exercises frequently for several months.

Ask your doctor for help if you're not sure whether you're exercising the right muscles. He or she may suggest trying biofeedback techniques. Biofeedback therapy uses a computer and electronic instruments to tell you when you're using the right pelvic floor muscles.

If you're a woman, your doctor might recommend vaginal cones. These are weights that you hold in your vagina that help you strengthen the pelvic floor.

Medicines

Your doctor may prescribe you a medicine called duloxetine. This medicine increases the activity of the nerve that stimulates the urethral sphincter to improve how well it works and prevent leaks. Duloxetine isn't suitable for everyone, as there are side-effects, so always ask your doctor for advice and read the patient information leaflet that comes with your medicine.

If you're a woman and your stress incontinence is being caused by a lack of oestrogen, your doctor might prescribe you an oestrogen cream or oestrogen tablets to insert into your vagina.

Non-surgical treatments

Some people might find that neuromuscular stimulation of the pelvic floor is helpful. This is suitable for both men and women. A probe is placed into the vagina (for women) or rectum (for men). The probe has an electrical current that can help to exercise and strengthen the pelvic floor muscles.

Injections of bulk-forming agents, such as collagen, around your urethra can be effective. This helps keep your urethra closed and reduces urine leakage. The procedure is usually done by a urological specialist and takes around five minutes, although you will probably need to have repeat injections. You will have a local anaesthetic for this treatment – this completely blocks pain from the area and you will stay awake during the procedure.

Surgery

If you have severe stress incontinence and other treatments haven't been effective, your doctor might recommend that you have surgery to strengthen or tighten the tissues around your urethra. As with every procedure, there are some risks associated with having surgery for bladder problems. Talk to your doctor or surgeon about your surgical options and the risks that are associated with each one.

Surgical options include the following.

- Tension-free vaginal tape – for women only. During this procedure, your surgeon will make a small incision in the wall of your vagina. He or she will then insert a mesh tape into the incision, which lies between the vagina and the urethra. This supports the middle of the urethra and stops any leaks when your bladder comes under any sudden pressure. The procedure may be done under general or local anaesthetic, depending on medical factors. A general anaesthetic means you will be asleep during the procedure. Tension-free vaginal tape isn't suitable for all women, especially if you're considering having children.

- Sling procedures – for both men and women. A sling is a piece of human or animal tissue, or a synthetic tape that your surgeon places to support your bladder neck and urethra. This is more commonly done in women. There is a simpler type of sling implant that has been invented for men, which is usually very successful. However, it's not suitable for men who have total incontinence or after radiotherapy.

- Burch colposuspension – for women only. Your surgeon will make a large cut in your abdomen (tummy) and lift the bladder neck upwards. He or she will then sew the lower part of the front of your vagina to a ligament behind the pubic bone to help prevent leaks. This operation requires a general anaesthetic and you will probably need to stay overnight in hospital.

- Artificial urinary sphincter – for both men and women. If your urinary sphincter doesn't close fully, it may be possible to have it replaced with an artificial one. This is implanted around the neck of your bladder and a fluid-filled ring (called a cuff) keeps your urinary sphincter shut tight until you're ready to pass urine. You then press a valve that is implanted under your skin to deflate the ring and allow you to urinate.

Availability and use of different treatments may vary from country to country. Ask your doctor for advice on your treatment options.

This section contains answers to common questions about this topic. Questions have been suggested by health professionals, website feedback and requests via email.

What are pelvic floor exercises and how do I do them?

What else can I do to make things feel better day to day?

What is bladder training?

What are pelvic floor exercises and how do I do them?

Answer

Pelvic floor exercises strengthen your pelvic floor muscles (the muscles that span your legs and support your bladder, uterus and bowel). You can exercise these muscles by squeezing them as if you're trying to stop wind or urine escaping.

Explanation

Most women with stress or mixed incontinence are told to do pelvic floor exercises before they are given medicine or surgery. Some women have mild pain or discomfort when they do the exercises, but usually this treatment has no side-effects.

You need to do pelvic floor exercises at least three times a day, over a period of at three months before you can tell if they are working. If they have worked, then you will need to do them for the rest of your life to maintain the benefits.

The following instructions tell you how to do pelvic floor exercises.

- To find your pelvic floor, imagine stopping yourself from passing urine or wind.

- Tighten the muscles around your vagina, your urethra (the tube that carries urine from your bladder out of your body) and your back passage. It feels like a squeeze and lift inside.

- Squeeze and lift for ten seconds as strongly as you can. Rest for ten seconds and repeat ten times. Follow with ten fast squeezes. Repeat this three times a day.

- Breathe normally as you do the exercises.

- Try not to squeeze your buttocks or legs together.

- You can do the exercises while you're standing, sitting or lying down. No one can see you do them. Try and set a routine, for example, every time you wash your hands, or clean your teeth.

- Treatments such as vaginal cones and biofeedback can help alongside pelvic floor exercises.

- Talk to your GP or nurse for more information. Your GP can refer you to a physiotherapist or a continence nurse who can teach you how to do these exercises if you're unsure.

What else can I do to make things feel better day to day?

Answer

Incontinence can have a major impact on your life. It can affect your work, relationships, social life and emotional wellbeing. Many women are too embarrassed to get help and some see it as a natural part of getting older. However, there are many things you can do to help you feel more comfortable and in control.

Explanation

It's really important not to ignore the problem, hoping it will go away. Around one in three women never seek help for incontinence and suffer in silence. The first step is to speak to your GP as soon as the problem starts. Your GP may refer you to a continence nurse, who can give you specialist advice.

There are also organisations that can help by providing you with information as well as emotional and practical support to help you deal with your feelings and worries.

Practical tips that may help include:

- Eat plenty of fruit, vegetables and other foods containing fibre. Make sure you drink enough fluids and try to do 150 minutes (two and a half hours) of moderate exercise over a week in bouts of 10 minutes or more. You can do this by carrying out 30 minutes on at least five days each week. This will help you to avoid constipation, which can make incontinence worse.

- If you take diuretic medicines (water tablets) for a health condition, such as high blood pressure, they may affect your incontinence. Try varying the times when you take your tablets and ask your GP whether there are any other medicines that you could try.

- Try the wide range of pads and knickers available over-the-counter from your chemist. You might want something slim and discreet during the day but something more bulky at night.

- Look after your skin. Urine can irritate your skin. As well as leaving your skin red and sore, it can also cause it to break down. Clean and dry your skin thoroughly as soon as possible after any incontinence.

What is bladder training?

Answer

Bladder training is a treatment that can help if you have mixed incontinence or urge incontinence. It works best if your symptoms are mild. You learn how to ignore or suppress the need to pass urine. Eventually you will have fewer strong urges to pass urine and can get into a more regular pattern. You will need to try bladder training for at least six weeks to know whether it's working or not.

Explanation

Bladder training works by increasing the time between each visit to the toilet, and so increasing the amount of urine you pass each time you go. Learning how to train your bladder is something that is done most effectively when your nurse can help you, but it's possible for you to learn how to train your bladder yourself.

The four steps to bladder training are as follows.

- Keep a bladder diary to record when you go to the toilet to pass urine, what you drink and how long you can wait until you have to go.

- From your records, you will be able to work out how long your bladder can hold before you need to visit the toilet. Set your first target to improve on this. For example, if you pass urine every hour, set your first target to pass urine every hour and a half.

- To hold on for this extra time, you need to distract yourself. Sitting on a hard chair or a rolled up towel can help, as can squeezing your pelvic floor muscles. You may need to take small steps to get to your target, for example, increasing by five minutes at a time.

- Once you've achieved your target, set a new one. Keep going until you're going to the toilet to pass urine every three or four hours and your symptoms of urgency have gone. It can take several weeks or even months to get to this stage.

- If you feel there's no improvement at all after two to three weeks, contact your GP.

Further information

-

The Bladder and Bowel Foundation

0845 3450165

www.bladderandbowelfoundation.org -

The Chartered Society of Physiotherapists

www.csp.org.uk

Sources

- Incontinence. Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. www.csp.org.uk, accessed 3 November 2011

- Stress urinary incontinence. The Bladder and Bowel Foundation. www.bladderandbowelfoundation.org, accessed 3 November 2011

- Urinary incontinence. The Merck Manuals. www.merckmanuals.com, published October 2007

- Urinary incontinence in women. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. www.kidney.niddk.nih.gov, published September 2010

- Urinary incontinence in women. BMJ Best Practice. www.bestpractice.bmj.com, published April 2011

- Personal communication, Mr Raj Persad, Consultant Urologist, Bristol Royal Infirmary, 5 December 2011

- Stress urinary incontinence treatments. The Bladder and Bowel Foundation. www.bladderandbowelfoundation.org, accessed 7 November 2011

- Start active, stay active: a report on physical activity from the four home countries’ Chief Medical Officers. Department of Health, 2001. www.dh.gov.uk

- Urinary incontinence treatment and management. eMedicine. www.emedicine.medscape.com, published October 2011

- Artificial urinary sphincter placement. eMedicine. www.emedicine.medscape.com, published May 2011

- Pubovaginal sling procedures. eMedicine. www.emedicine.medscape.com, published October 2011.

- Personal training for your pelvic floor muscles. The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. www.csp.org.uk, published April 2011

- Urinary incontinence: facts and statistics. National Association for Continence. www.nafc.org, accessed 17 October 2012

- Diokno AC. Incidence and prevalence of stress urinary incontinence. Adv Stud Med 2003; 3(8E):S824–S828

- Physical activity and adults. World Health Organization. www.who.int, accessed 17 October 2012

Produced by Alice Rossiter, Bupa Health Information Team, January 2012.