Bladder cancer

Bladder cancer is caused by the uncontrolled growth of cells that line the bladder wall. In the UK, more than 10,000 people are diagnosed with bladder cancer each year. Bladder cancer is usually treated with surgery, chemotherapy, immunotherapy or radiotherapy.

How cancer develops

The bladder

About bladder cancer

Types of bladder cancer

Symptoms of bladder cancer

Causes of bladder cancer

Diagnosis of bladder cancer

Treatment of bladder cancer

Prevention of bladder cancer

Living with bladder cancer

How cancer develops

The information on the video provided does not constitute advice on diagnosis or the treatment for heart disease and such advice should always be sought from a doctor or another suitably qualified health professional.

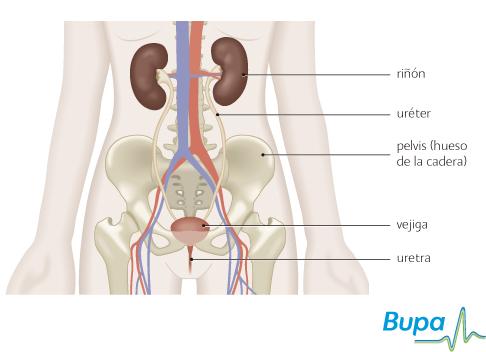

The bladder

Your bladder is a hollow, muscular, balloon-like organ that collects and stores urine. Urine is produced by your kidneys which ‘clean’ your blood by filtering out water and waste products to make urine. The urine is passed from your kidneys through tubes (called the ureters) into your bladder and then to the outside (through the urethra).

About bladder cancer

Bladder cancer develops in the lining or the wall of your bladder. It’s caused by the uncontrolled growth of cells. Bladder cancer mostly affects people over 50 and is more common in men than in women.

Types of bladder cancer

There are different types of bladder cancer, named after the type of cell the cancer first occurs in and how far it has spread. These are described below.

- Transitional cell carcinoma (TCC). This type of cancer is the most common bladder cancer and develops in the top layer of cells that line the bladder wall. These cells come into contact with waste products in the urine that may cause cancer.

- Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). This type of cancer develops in the flat cells that line the bladder wall.

- Adenocarcinoma. This is a very rare type of bladder cancer that develops in the mucus-producing cells that line the bladder wall.

- Superficial (non-muscle invasive) bladder cancer. The cancer is only in the bladder lining and hasn’t spread into the deeper layers of the bladder wall. Superficial bladder cancer is usually early stage transitional cell bladder cancer. It usually appears as a small mushroom-like growth on the lining of the bladder (called papillary cancer).

- Invasive bladder cancer. The cancer has spread into the muscle wall of the bladder. Transitional cell bladder cancer can become invasive. Depending on how far it has spread, invasive bladder cancer is divided into T2, T3 or T4. For more information, see cancer staging and grading.

Symptoms of bladder cancer

Symptoms of bladder cancer include:

- a burning feeling when passing urine

- a need to pass urine frequently

- feeling the need to urinate but not being able to

- pain in your pelvis

- blood in urine

These symptoms aren’t always due to bladder cancer but if you have them, visit your GP.

Causes of bladder cancer

Doctors don’t fully understand why bladder cancer develops. However, certain factors make bladder cancer more likely.

- Smoking triples your risk of bladder cancer. Passive smoking may also increase your risk.

- Exposure to certain industrial chemicals (for example, those used in printing and textiles, gas and tar manufacturing, iron and aluminium-processing industries).

- A long-term infection with the tropical disease, schistosomiasis (bilharzia).

- A long-term or repeated bladder infection.

Diagnosis of bladder cancer

Your GP will ask about your symptoms and examine you. You may be referred to a urologist (a doctor who specialises in identifying and treating conditions that affect the urinary system).

You may have the following tests to confirm diagnosis.

-

Cystoscopy. This is a procedure used to look inside the bladder and urinary system. During the procedure, your surgeon may take a biopsy (a small sample of tissue). This will be sent to a laboratory for testing to determine the type of cell and whether they are benign (not cancerous) or cancerous.

-

Intravenous urogram (IVU). This is a special type of X-ray procedure used to look inside the bladder and urinary system. A dye is injected into your bloodstream through a vein in your arm. The dye is removed from your blood by your kidneys and X-ray images show the dye travelling through your urinary system. This helps your surgeon check for anything unusual.

- Ultrasound, MRI scan or CT scan. These scans can help doctors to check your urinary system to see if the cancer has spread.

Treatment of bladder cancer

Treatment depends on the position and size of the cancer in your bladder and how far it has spread.

Your doctor will discuss your treatment options with you.

Transurethral resection of bladder tumour (TURBT)

This is a procedure used to remove any unusual growths or tumours on the bladder wall. Using a rigid cystoscope a special wire loop is passed into your bladder. An electric current is passed down the wire loop and used to cut or burn off the growth or tumour and a border of healthy tissue around it. For more information, see transurethral resection of bladder tumour, TURBT.

Bladder treatment with mitomycin C or Bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG)

Mitomycin C is a chemotherapy medicine used to destroy cancer cells. BCG is an immunotherapy that contains a weak form of the bacterium Mycobacterium bovis, which is also used to vaccinate against tuberculosis (TB). BCG works by encouraging the immune system to attack cancer cells. Mitomycin C or BCG treatment is usually given after bladder surgery, sometime it may be used alone to treat bladder cancer. For more information, see bladder treatment with mitomycin C or Bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG.

Surgery (complete or radical cystectomy)

Removing your bladder and surrounding tissues is the main treatment for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. The operation is called a complete or radical cystectomy. It is usually followed by radiotherapy.

You may be given radiotherapy or chemotherapy to shrink the tumour before surgery.

After removing your bladder, your surgeon will create a new area for you to store urine. There are several ways to do this and the three main options are listed here.

-

Urostomy. Your ureters are connected to a small opening (a stoma) in your abdomen (tummy) using a short piece of your small bowel. A flat, watertight bag is placed over the stoma to collect your urine.

-

Continent urinary diversion. A section of bowel is used to make a pouch inside your abdomen to collect urine. The pouch is connected to the outside of your body via a stoma which is kept closed with a valve. You will need to empty the pouch four to five times a day by inserting a catheter into the stoma.

- Bladder reconstruction. A new bladder is made using part of your bowel. Your urine drains from your ureters into the new bladder. You will need to learn how to pass urine through your urethra by using your muscles. You will have lost the nerves that tell you when your bladder is full and so will need to remember to empty it.

Prevention of bladder cancer

Making sure you get enough vitamin D can reduce your risk of developing a number of cancers, including bladder cancer. Vitamin D is produced naturally by your body when your skin is exposed to sunlight and can also be obtained from some foods, such as oily fish. However, most people don't get enough from these sources. This is especially true if you live in a region that is nearer the North or South Pole than the equator (for example the UK, Canada or southern Argentina), where the sunlight to make vitamin D is only strong enough during the summer.

You can reduce your risk of developing bladder cancer by stopping smoking and taking 35 to 50 micrograms of vitamin D a day (about three to four high-strength, 12.5 microgram tablets). Always read the patient information leaflet that comes with your supplements and if you’re pregnant or breastfeeding, ask your pharmacist or GP for advice first. Talk to your GP before taking vitamin D supplements if you’re taking diuretics for high blood pressure or have a history of kidney stones or kidney failure.

Living with bladder cancer

After treatment for bladder cancer, you will have regular check-ups with your doctor. Many hospitals have stoma nurses who can help you take care of your urostomy and give you advice.

Being diagnosed with cancer can be distressing for you and your family. Specialist cancer doctors and nurses are experts in providing the care and support you need. There are support groups where you can meet people who may have similar experiences to you. Ask your doctor for advice.

Can bladder cancer be detected with a urine test?

Will treatment for invasive bladder cancer affect my sex life?

How will having a urostomy affect my everyday life?

Can bladder cancer be detected with a urine test?

A urine test is usually done to determine if your symptoms are caused by a bladder infection and to detect any blood present in the urine. Bladder cancer is usually diagnosed by taking a biopsy from your bladder wall.

Explanation

At present, bladder cancer is diagnosed by doing a cystoscopy and taking a biopsy from your bladder wall. There are however, a number of tests being developed that may make it possible to diagnose bladder cancer from a sample of urine.

-

NMP22 (nuclear matrix protein 22) test. This checks levels of the protein NMP22 in your urine. Some NMPs have been found in the cells of certain types of bladder cancer including the most common type, transitional cell cancer (TCC). NMP22 levels are often higher in the urine of people with TCC than people with a healthy bladder.

-

Mcm5 (minichromosome maintenance 5) test. This checks levels of the protein Mcm5 in your urine. This protein is made by some types of cancer cell including TCC. Mcm5 levels are often higher in the urine of people with TCC than people with a healthy bladder.

- BTA (bladder tumour-associated antigen) test. This test uses two monoclonal antibodies (proteins made in a laboratory) to look for particular cancer proteins in your urine. Levels of the protein BTA are usually higher in people with bladder cancer than people with a healthy bladder.

These tests may help to pick up a new bladder cancer or one that has come back after treatment. They are still being investigated and aren’t available in the UK yet. Even if they do become available, they are unlikely to be used alone to diagnose bladder cancer – a cystoscopy and biopsy will probably still be needed to confirm the result.

Will treatment for invasive bladder cancer affect my sex life?

Treatment for invasive bladder cancer may result in physical changes that could affect your sex life. In men, the operation to remove the cancer may damage the nerves that control erections and in women, an operation to remove the urethra may shorten or narrow the vagina.

Explanation

- For men Although great care will be taken, there is a risk that the nerves in your pelvis will be damaged during the operation. If you have problems getting an erection after surgery, there are several options that may help.

-

Medicines. Your doctor may prescribe a medicine that you take as a tablet. This can help you to get an erection by increasing the blood flow to your penis. Examples include sildenafil (Viagra), vardenafil (Levitra) and tadalafil (Cialis). The tablets are taken at various times before sex (for example, sildenafil is taken about one hour beforehand). Alternatively, your doctor may prescribe medicines that you need to inject directly into your penis, or pellets that you insert into the tip of your penis, to give you an erection.

-

Vacuum pumps. These devices draw blood into your penis to create an erection, which is maintained by placing a rubber ring around the base of your penis. After sex, you remove the ring and your blood flows normally again.

- Penile prostheses. Mechanical devices can also be used to create an erection. You can have an operation to insert flexible rods or thin inflatable cylinders into your penis.

- For women If surgery has shorted or narrowed your vagina, it may help to use a dilator to stretch it. Dilators are metal or plastic objects shaped like a tampon. You insert them into your vagina for a few minutes every day. Over a few weeks you gradually use larger sizes and this slowly stretches your vagina. Having regular, gentle sex will also have the same effect.

Ask your doctor if you have any concerns about sex after treatment for bladder cancer.

How will having a urostomy affect my everyday life?

It may take time and practice to learn how to look after the urostomy but most people are able to return to their jobs, everyday activities, and hobbies. Most hospitals have specialist stoma care nurses who can give you advice and support.

Explanation

When you have surgery to remove your bladder, your surgeon will create a new way for you to store urine. A urostomy is the commonest operation.

Your surgeon will remove a small piece of your small bowel and will join one end of the piece of bowel to your ureters and the other end to a small hole cut into the surface of your abdomen. The hole is called a stoma. The position of the stoma is usually to the right of your tummy button. However, before your operation your surgeon or nurse will help you plan the position of the stoma that best suits you.

After the operation, urine will pass down your ureters, but instead of going into your bladder it will run through the piece of bowel and out onto the surface of your abdomen. A waterproof bag (a urostomy bag) is placed over the stoma to collect your urine. The bag stays in place with glue. You will need to empty the bag as often as you would normally go to toilet to pass urine.

Your nurse will show you how to clean the stoma and change the bags. Modern urostomy bags are very well designed. They shouldn’t leak and are hardly noticeable under clothing. You can wear a smaller bag for exercising or a waterproof dressing for swimming.

Talk to your nurse if you have any problems or concerns.

Further information

- Macmillan Cancer Support

0808 808 00 00

www.macmillan.org.uk

- Urostomy Association

08452 412159

www.uagbi.org

Sources

- Bladder cancer. Cancer Research UK. www.cancerhelp.org.uk, published June 2010

- Bladder cancer. Macmillan. www.macmillan.org.uk, accessed 28 July 2010

- Electrically-stimulated intravesical chemotherapy for superficial bladder cancer. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), November 2008. www.nice.org.uk

- Babjuk M, Oosterlinck W, Sylvester R, et al. Guidelines on TaT1 (non-muscle invasive) bladder cancer. European Association of Urology 2010. www.uroweb.org

- Stenzl A, Cowan NC, De Santis M, et al. Guidelines on bladder cancer: muscle-invasive and metastatic. European Association of Urology 2010. www.uroweb.org

- van Rhijn BW. Considerations on the use of urine markers for bladder cancer. Eur Urol 2008; 53(5):909–16

- Horizon scanning technology prioritising summary: NMP22 BladderChek diagnostic test for bladder cancer. Australia and New Zealand Horizon Scanning Network. www.horizonscanning.gov.au, published November 2009

- What is a urostomy? Urostomy Association. www.urostomyassociation.org.uk, published October 2008

Related topics

- Bladder treatment with mitomycin C or Bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG)

- Chemotherapy

- Cystoscopy

- Radiotherapy

- Transurethral resection of bladder tumour (TURBT)

Published by Bupa’s Health Information Team, October 2010.