Bronchiolitis in children

Bronchiolitis is a breathing condition caused by a viral infection. Infants between three and six months are most commonly affected, though it can occur up to two years. It’s estimated that around one in three infants will develop bronchiolitis in their first year of life. It's most common during the winter months.

About bronchiolitis

Symptoms of bronchiolitis

Complications of bronchiolitis

Causes of bronchiolitis

Diagnosis of bronchiolitis

Treatment of bronchiolitis

Prevention of bronchiolitis

About bronchiolitis

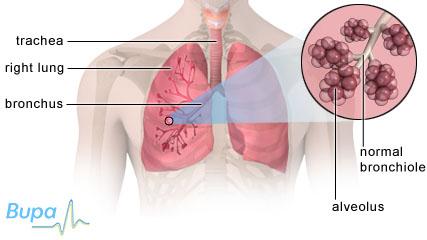

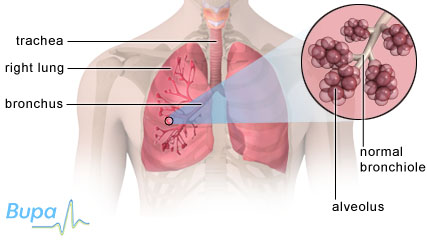

The bronchioles are the small tubes inside your lungs. When you breathe in, air flows into your windpipe and down into your lungs via a series of branching tubes called bronchi. Inside your lungs, the bronchi branch into the smaller bronchioles, which end in millions of tiny air sacs (alveoli). When the air enters the alveoli, oxygen from the air is transferred to your blood, which is then transported around your body.

If your child has bronchiolitis, the bronchioles become inflamed and lined with excess mucus which can make it difficult for him or her to breathe.

Bronchiolitis is caused by one of a number of different viruses. In three-quarters of cases it is caused by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

Symptoms of bronchiolitis

Your child's symptoms may include:

- a fever (a temperature higher than 37.5˚C)

- a runny or blocked nose

- a cough

- difficulty feeding

- breathing quicker than usual

- finding it harder than usual to breathe

- wheezing

- stopping breathing for very brief periods of time (known as apnoea)

For most children, bronchiolitis isn't serious and your child will get better within a couple of weeks. If you’re at all worried or the symptoms get worse, you should take your child to the GP.

It’s important that you watch closely for the following symptoms and seek urgent medical attention if your child is:

- feeding less than half the amount he or she usually does

- very tired or lethargic

- flaring his or her nostrils or making grunting noises when breathing

- having difficulty breathing - you may see the muscles under your child's ribs or the skin between the ribs sucking in with each breath

- turning a bluish skin colour (known as cyanosis)

- having repeated episodes of apnoea

Complications of bronchiolitis

Rarely, children can get another infection (known as a secondary infection) in addition to the virus causing their bronchiolitis. This can cause pneumonia.

A few babies become seriously ill and need to be treated in the intensive care unit for specialist help with their breathing.

Bronchiolitis rarely causes long-term breathing problems, but your child may have a wheezy cough for a while after the illness.

Causes of bronchiolitis

Bronchiolitis is caused by one of a number of different viruses. In three-quarters of cases it is caused by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

The viruses that cause bronchiolitis can easily spread from one person to another. They can be transferred through the air by coughing and sneezing or by direct contact (person-to-person or through materials that have been in contact with an infected person).

There are certain factors that can make severe bronchiolitis more likely:

- premature birth

- congenital heart disease

- parental smoking

- bottle feeding (as compared with breastfed babies)

- sharing a bedroom with older brothers and sisters (especially siblings who go to nursery or school)

The younger your baby and the more premature his or her birth, the higher the likelihood he or she will need hospital treatment for bronchiolitis

Diagnosis of bronchiolitis

Your GP will ask about your child's symptoms and medical history. He or she will also examine your child by listening to his or her chest with a stethoscope.

If your GP thinks that your child is showing signs of severe bronchiolitis, he or she will refer you to the nearest hospital, where the hospital doctor will do further tests. These tests include:

-

putting a pulse oximeter on your child’s finger or toe – this measures the oxygen in your child’s blood

- taking a sample of fluid from your child's nose – this can help identify which virus is causing the bronchiolitis

In some severe or unusual cases, the hospital doctors may recommend various blood tests, a urine test and/or and X-ray of your child’s chest.

Treatment of bronchiolitis

Your child will usually get better within a couple of weeks. There are a number of treatments you can give your child at home to help ease his or her symptoms.

-

Liquid paracetamol (eg Calpol) can help to lower a fever and ease any pain. You can get liquid paracetamol without prescription from your pharmacist. Always read the patient information leaflet that comes with the medicine. Never give your child aspirin

-

Make sure your child drinks enough fluids

- Saline nose drops available from a pharmacy may help a blocked nose

If your child is treated in hospital, he or she may receive one or more of the following treatments.

-

Fluids – if your child is struggling to feed, he or she may be dehydrated. Fluids can be given through a nasogastric or orogastric tube (a tube placed in the nose or mouth and fed down into the stomach). Alternatively, your child may be given fluid through a drip

- Mucus causing congestion in your child's nose can be suctioned out

- Extra oxygen can be given through a mask or tube in your child's nose

Prevention of bronchiolitis

It's very difficult to prevent your child from getting bronchiolitis because the viruses which cause it are so common.

However, there are some measures you can take to reduce the chance of your child getting bronchiolitis. Or, if your child is already infected, you can minimise the chance of it spreading to others.

-

Make sure everyone in your household washes their hands frequently

-

Keep your child home from childcare or school until their fever has gone down, their cough is almost gone and they feel well enough to attend

-

Keep your child away from people who have a cold or flu

-

Teach your child to cover his or her mouth

-

Use disposable tissues and throw them away immediately after use

- Don't smoke, or let others smoke, near your child

This section contains answers to common questions about this topic. Questions have been suggested by health professionals, website feedback and requests via email.

The GP said my child has bronchiolitis. Why didn't he prescribe antibiotics?

Can older children and adults catch the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)?

How do I know if my baby is dehydrated?

The GP said my child has bronchiolitis. Why didn't he prescribe antibiotics?

Answer

Your GP didn't prescribe antibiotics for your child as they aren’t effective against infections caused by viruses.

Explanation

Bronchiolitis is usually caused by a virus, most commonly respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Antibiotics are given to fight bacterial infections; they aren’t effective against infections caused by viruses.

Rarely, children may get a bacterial infection in addition to the viral infection causing the bronchiolitis. In these circumstances antibiotics may be needed, or they may be given to your child as a precaution.

Can older children and adults catch the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)?

Answer

Yes, older child and adults can catch RSV, but symptoms are usually milder than in infants.

Explanation

Almost all children will have been infected with RSV by the age of two, often causing little more than a regular cold. It’s estimated that around one in three infants will develop bronchiolitis (caused by RSV) in their first year of life.

However, older children and adults can become re-infected with RSV. The symptoms are generally milder than in young infants. Otherwise healthy older children and adults may get bronchitis or influenza-like symptoms. Older people, and those who have suppressed immune systems (such as after an organ transplant or certain cancer treatments), may develop more severe symptoms.

How do I know if my baby is dehydrated?

Answer

There are a number of ways to detect whether your baby is dehydrated. For example, dark-coloured urine or a dry nappy for three hours or more, are signs to look out for.

Explanation

If your child has bronchiolitis, he or she may find it difficult to feed and this can lead to dehydration. If you’re breast or bottle-feeding your baby, continue to feed as normal. But if he or she is reluctant to feed, offer more frequent, small feeds. Feeding little and often can help keep your child hydrated.

If your child is making less urine than usual (fewer wet nappies), this is a key indicator that he or she may be dehydrated.

Other signs of dehydration include:

- a sunken fontanelle (the soft spot on top of the head)

- a dry mouth

- sunken eyes

- a poor overall appearance (pale or blotchy skin for example)

- tiredness

If there are any signs at all that your child may be dehydrated, you should seek medical advice immediately.

Further information

-

British Lung Foundation

08458 50 50 20

Sources

- Bronchiolitis in children, a National Clinical Guideline. SIGN, 2006. www.sign.ac.uk

- Bronchiolitis and your baby. British Lung Foundation. www.lunguk.org, accessed 07 November 2009

Related topics

Asthma in children

Bronchiolitis

Fever in children

Pneumonia

X-ray