Down’s syndrome

Down’s syndrome (also known as trisomy 21) is a condition that causes delays in learning and development. People with Down’s syndrome are born with an extra chromosome. About one in 700 babies are born with Down’s syndrome in the UK.

About Down’s syndrome

Symptoms of Down’s syndrome

Complications of Down’s syndrome

Causes of Down’s syndrome

Diagnosis of Down’s syndrome

Living with Down’s syndrome

About Down’s syndrome

Down’s syndrome is caused by an extra chromosome. Chromosomes are structures that contain genes – these contain the instructions for life and are inherited from parents. Normally, our cells contain 46 chromosomes: 23 inherited from each parent. In Down’s syndrome a mistake is made during cell division, this is most likely to occur when the sperm or egg is being formed causing 24 chromosomes to be present rather than the usual 23. After the egg is fertilised by the sperm the cells have 47 chromosomes rather than the normal 46 chromosomes.

Types of Down’s syndrome

- Trisomy 21 – this is when all the cells have an extra chromosome 21. This happens in most people with Down’s syndrome.

- Translocation – this is when an extra fragment of chromosome 21 attaches to another chromosome. This happens in about one in 25 people with Down’s syndrome.

- Mosaicism – this is when only some cells have an extra chromosome 21 while others don’t. This happens in about one in 50 people with Down’s syndrome.

Symptoms of Down’s syndrome

The extra chromosome 21 causes characteristic physical features in people with Down’s syndrome. These usually include some, but not always all, of the following.

- Low-set eyes that slope upwards, with vertical skin folds (epicanthic folds) between the upper eyelids and the inner corner of the eye.

- A small mouth, which means the tongue may seem big and may stick out.

- A flattening at the back of the head.

- A flattened nose bridge.

- Broad hands with a single crease.

- Floppiness due to loose muscle tone.

- Small, low-set ears.

- A low birth weight and short stature.

Many of these physical features can be found in the general population; having some of these characteristics doesn’t necessarily mean that a person has Down’s syndrome.

Complications of Down’s syndrome

People with Down’s syndrome are more likely to have the following.

- Heart problems.

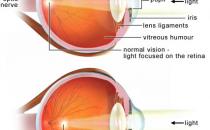

- Eye problems, such as short- or long-sightedness or cataracts (cloudy patches in the lens of the eye).

- Hearing problems, ranging from mild to complete deafness.

- Thyroid problems, including low or more rarely, high levels of the thyroid hormones.

- Poor immunity and so are prone to chest infections, coughs and colds.

- Problems with the digestive system, such as persistent diarrhoea or constipation; babies may have feeding problems and may not gain weight normally.

- Dementia at an earlier age (it occurs 20 to 30 years earlier than in the rest of the population).

It’s important for people with Down’s syndrome to have regular health checks so that these conditions can be diagnosed and treated at an early stage.

Development

All people with Down’s syndrome have some level of learning disability but the severity can differ between individuals. Children usually learn to walk, talk, read and write, but more slowly than other children of their age. People with Down’s syndrome learn to do things throughout their lives at different rates.

Causes of Down’s syndrome

Down’s syndrome is caused by an extra chromosome. This happens as a result of a problem in cell division but it’s not known what causes that to happen. However, the chance of having a baby with Down’s syndrome increases with the mother’s age. For women, the chance of having a baby with Down’s syndrome at:

- age 20 – is one in 1500

- age 30 – is one in 900

- age 40 – is one in 100

However, most babies with Down’s syndrome are born to women under 35, since these women account for the majority of the childbearing population.

The chance of you having a baby with Down’s syndrome has nothing to do with where you live, your social class or your race. You can’t do anything before or during pregnancy to change the chance of your baby having Down’s syndrome.

Diagnosis of Down’s syndrome

Babies with Down’s syndrome are usually diagnosed in the first few days after birth. Doctors and midwives are trained to identify the physical characteristics associated with the condition. Some babies have almost no physical signs while others have all of them. A chromosome test is then used to confirm the diagnosis. The doctor will take a blood sample from the baby. This is sent to a laboratory for tests.

There are also screening tests for Down’s syndrome that you can have while you’re pregnant. Screening takes place during either the first trimester (three months) or second trimester (six months) by either ultrasound or through a blood test, or a combination of both. Screening tests don’t give a definite answer, but can tell you if your baby has an increased risk of having Down’s syndrome.

If the screening tests show that your baby has an increased risk of having Down’s syndrome; you will be offered further diagnostic tests, such as chorionic villus sampling (following a first-trimester screening test) or amniocentesis (following a second-trimester screening test). These tests involve some risk to mother and baby so are usually only offered to women if earlier screening tests suggest the baby is likely to have Down’s syndrome. For more information about these tests, see related topics.

Living with Down’s syndrome

People with Down’s syndrome have special medical and social needs, but they can live full lives, take part in further education, have jobs and relationships, and live independently.

Medical and social support

A team of professionals will help support people with Down’s syndrome, and their families. This team may include your GP, a paediatrician, midwife, health visitor, occupational and speech therapists and a physiotherapist for example.

Specialist doctors monitor all babies with Down’s syndrome for health problems, and children with the condition have regular growth, hearing and sight, and thyroid checks. It’s also important for adults with Down’s syndrome to have regular sight, hearing and thyroid function tests.

Occupational therapists and dieticians can help with issues such as nutrition and educational support. Most children with Down’s syndrome go to mainstream schools, but there are schools for children with special needs.

Answers to questions about Down’s syndrome:

My baby’s got Down’s syndrome. Will I still be able to breastfeed?

Can people with Down’s syndrome have children?

Is there a cure for Down’s syndrome?

Is it my fault that my baby has Down’s syndrome?

How will Down’s syndrome affect my child’s development?

What can I do to help my child reach her full potential?

My baby’s got Down’s syndrome. Will I still be able to breastfeed?

Yes, it’s very likely that your baby will be able to breastfeed, although it may take slightly longer than usual. You can get extra help from a breastfeeding counsellor if you need it.

Explanation

Your baby may be able to breastfeed straight away. However, some babies with Down’s syndrome don’t breastfeed fully at first. This is because they often have poor muscle tone. This means they are unable to tense their muscles as much as other babies, which can make it harder for them to suck.

Your baby may also find it slightly harder to stay attached to your breast. To help your baby feed, support his or her chin with your free hand. Babies get tired quite easily so try to give feeds little and often. If you still find it difficult to breastfeed, speak to your midwife or health visitor.

A few babies with Down’s syndrome have other associated conditions, such as digestive disorders. These can affect feeding and may need treating before your baby is able to breastfeed.

There are many advantages of breastfeeding, and it may help you to bond with your baby. However, it doesn’t suit all mothers and you shouldn’t feel guilty if you can’t breastfeed your baby.

Can people with Down’s syndrome have children?

People with Down’s syndrome may be able to have children, but very few do. If you have a child with Down’s syndrome, it’s important to teach them about safe sex and birth control.

Explanation

Women with Down’s syndrome may still be able to have children although it’s harder for them to conceive. Men with Down’s syndrome have reduced fertility, although there is evidence that two men with Down’s syndrome have become fathers.

The possibility of having children raises a number of issues for people with Down’s syndrome. They are likely to find it harder to cope with the responsibility and added costs of parenthood without a lot of support. Their baby may also have the condition. The risk of a baby having Down’s syndrome is very high if both parents have the condition.

When your child becomes a teenager, he or she will need to learn about the usual changes of puberty. Most will want to have a boyfriend or girlfriend. It can help to teach your child honestly about the possibility of sexual relationships early in life. Explain that sex can be part of a close, adult relationship and that there is a chance of pregnancy. Talk to your child about the need for contraception and how to protect against sexually transmitted infections.

Is there a cure for Down’s syndrome?

No, Down’s syndrome is a lifelong condition. However, by making the most of the support available, you can help your child become more independent and lead a fulfilling life.

Explanation

Down’s syndrome is caused by a problem with an individual’s genetic material, and this can’t be reversed. However, people with Down’s syndrome have access to much more support and better medical care today than they did in the past. You can get support from your:

- midwife or health visitor

- GP

- paediatrician (a doctor who specialises in children’s health)

- social worker

- child development centre community team for learning disabilities

- speech therapist and occupational therapist

- physiotherapist (a health professional who specialises in movement and mobility)

- dietitian

People with Down’s syndrome are at risk of having a range of other medical conditions, such as cataracts and respiratory infections. Regular visits to your GP can help your doctor check for these conditions and treat them at an early stage.

With the right support and medical attention, people with Down’s syndrome can go to school and college, have a job and lead full lives.

Is it my fault that my baby has Down’s syndrome?

No, there isn’t any evidence that anything parents do before or during pregnancy can cause Down’s syndrome.

Explanation

Some mothers are concerned that they may have caused Down’s syndrome because of something they did during pregnancy. However, there is no evidence that any foods, pollution or actions are linked to your baby having Down’s syndrome. There is no reason for you to feel that you’re to blame.

Down’s syndrome is a result of your baby’s body cells having extra genetic material. It’s not fully understood what causes this to happen. However, the likelihood of having a child with Down’s syndrome is higher if:

- you are a mother over the age of 35

- you are parents who already have a child with Down’s syndrome

How will Down’s syndrome affect my child’s development?

Your child can learn to walk, talk and become toilet trained like other children, although it will probably take him or her longer.

Explanation

Children with Down’s syndrome take longer than other children to reach the basic developmental milestones. These include turning over, sitting, standing, walking and talking. Like any other child, there is a wide range of ability among children with Down’s syndrome.

The Down’s Syndrome Association says, as a general guide, your child is likely to:

- smile by about two months

- roll over between four and 22 months

- sit alone and crawl between six and 28 months

- say his/her first words between nine and 31 months

- walk between 12 and 65 months (average 24 months)

As they grow into adults, children with Down’s syndrome carry on learning, just like everyone else. You may be surprised at how much your child learns to do.

What can I do to help my child reach her full potential?

With patience and encouragement, you can help your child master many basic skills. There are also lots of early intervention programmes that offer support in all areas of child development.

Explanation

All children develop at different rates. There are some simple things you can do to help your child learn the basic skills.

You can help your baby learn to talk by speaking about the world around her. Look at your baby at the same time and show and name the objects you're talking about. Playing with your child can help to strengthen muscles and prepare her for walking.

Help your child learn to feed herself by sitting down together at mealtimes. Take this in small steps, starting by getting your child to pick things up with her fingers.

Try to make time each day to teach your child how to get dressed and help her practise doing this.

Make the most of the support available. Early intervention programmes can offer speech therapy and physiotherapy as well as home-based teaching programmes. They also give you the opportunity to meet other families who are facing the same challenges so you can support each other.

Further information

-

Down’s Syndrome Association

0845 230 0372

www.downs-syndrome.org.uk

Sources

- Antenatal care: Routine care for the healthy pregnant woman. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), March 2008. www.nice.org.uk

- Why is Down’s syndrome referred to as a genetic condition? Down’s Syndrome Association. www.downs-syndrome.org.uk, accessed 15 December 2009

- Learning about intellectual disabilities and health: Down’s syndrome. St Georges University of London. www.intellectualdisability.info, accessed 15 December 2009

- Basic medical surveillance essentials for people with Down’s syndrome. Cardiac disease: Congenital and acquired. UK Down’s Syndrome Medical Interest Group, 2007. www.dsmig.org.uk

- Basic medical surveillance essentials for people with Down’s syndrome. Ophthalmic problems. UK Down’s Syndrome Medical Interest Group, 2006. www.dsmig.org.uk

- Basic medical surveillance essentials for people with Down’s syndrome. Hearing impairment. UK Down’s Syndrome Medical Interest Group, 2004. www.dsmig.org.uk

- Basic medical surveillance essentials for people with Down’s syndrome. Thyroid disorder. UK Down’s Syndrome Medical Interest Group, 2001. www.dsmig.org.uk

- Down’s syndrome: Coeliac disease/gluten sensitivity. UK Down’s Syndrome Medical Interest Group. www.dsmig.org.uk, accessed 15 December 2009

- Health FAQs. Down’s Syndrome Association. www.downs-syndrome.org.uk, accessed 15 December 2009

- Can you tell the facts from the myths? Down’s Syndrome Association. www.downs-syndrome.org.uk, accessed 15 December 2009

- Schedule for health checks. UK Down’s Syndrome Medical Interest Group. www.dsmig.org.uk, accessed 15 December 2009

- Testing for Down’s syndrome in pregnancy. NHS Antenatal and Newborn Screening Programmes. www.fetalanomaly.screening.nhs.uk, accessed 15 December 2009

- Pre-conception - advice and management. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. www.cks.nhs.uk, accessed 15 December 2009

- Information for parents: Down syndrome. Department for Children SAF. http://publications.everychildmatters.gov.uk, accessed 15 December 2009

- Choosing the right school for your child: A guide for parents and carers. Mencap. www.mencap.org.uk, accessed 15 December 2009

- Down’s syndrome: A guide for new parents. Down’s Syndrome Association. www.downs-syndrome.org.uk, accessed 15 December 2009

- Pradhan M, Dalal A, Khan F, et al. Fertility in men with down syndrome: A case report. Fertil Steril 2006; 86(6):1765

- Van Cleve SN, Cannon S, Cohen W. Part 2: Clinical practice guidelines for adolescents and young adults with down syndrome: 12 to 21 years. J Pediatr Health Care 2006; 20(3):198–205

- National strategy for speech, language and communication: 2005-2010. Down’s Syndrome Association. www.downs-syndrome.org.uk, accessed 15 December 2009

Related topics

- Amniocentesis

- Cataracts

- Chorionic villus sampling

- Dementia

- Hearing loss

- Long-sightedness

- Overactive thyroid

- Short-sightedness

- Ultrasound in pregnancy

- Underactive thyroid

- Breastfeeding