Epidural for childbirth

An epidural stops you feeling pain from contractions during childbirth without putting you to sleep (unlike a general anaesthetic).

You will meet the anaesthetist carrying out your epidural to discuss your care. It may differ from what is described here as it will be designed to meet your individual needs. Details of the procedure may also vary from country to country.

How an epidural is given during childbirth

About having an epidural during childbirth

What are the alternatives?

Preparing for an epidural

What happens during an epidural

What to expect afterwards

What are the risks?

How an epidural is given during childbirth

About having an epidural during childbirth

An epidural stops you feeling pain without putting you to sleep. It can be used to provide pain relief during childbirth and can also be adapted to provide pain relief if you need to have a caesarean delivery.

An epidural involves injecting local anaesthetic and sometimes other pain-relieving medicines into your lower back, just above your waist. After an epidural, you shouldn't be able to feel any pain in your abdomen (tummy) or the tops of your legs.

Epidurals are usually very effective, but take about 30 minutes to work. If you have an epidural, your second stage of labour may take longer because you won't feel the urge to push. It may also make moving around more difficult because you will have less feeling in your back and legs.

However, you may be able to have a mobile epidural. This uses a lower dose of local anaesthetic plus an opioid painkiller. It allows you to walk about and use different positions that may make your labour easier.

How does an epidural work?

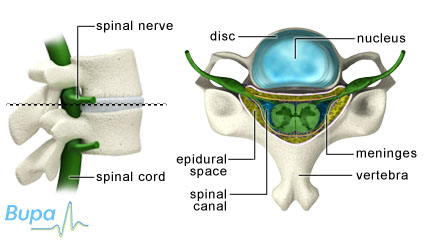

Your spinal cord runs through a channel formed by your vertebrae (bones in your spine) and is surrounded by three protective layers of tissue called the meninges. A protective layer of fluid lies between two of these tissue layers (this is known as the cerebrospinal fluid or CSF). The area just outside all these layers is called the epidural space.

Your spinal cord carries signals, in the form of electrical messages, between your brain and the network of nerves that branch outwards from your spine to all parts of your body. At each level of your spine, nerves leave your spinal cord to go to specific parts of your body. For example, nerves from the lower part of your body join your spinal cord in your lower back.

Your anaesthetist will inject the local anaesthetic into the epidural space in your lower back. This blocks the nerves in your spine that lead to the lower part of your body, stopping you feeling pain. Your anaesthetist can control how much feeling is lost, depending on the amount and type of medicines used. A caesarean delivery may be done with an epidural, without the need for you to have a general anaesthetic.

The different parts of the spinal cord

What are the alternatives?

There are several other methods of pain relief you may be able to try if you don't wish to have an epidural. Talk to your midwife or doctor about the risks and benefits of these.

- Gas and air (Entonox). This is a mixture of nitrous oxide and oxygen and is a mild painkiller. As you feel a contraction starting, you breathe the mixture in through a mouthpiece or a mask placed over your nose. It will probably make your contractions less painful, although not all women find it effective. It can sometimes make you feel sick or light-headed for a short time.

- Opioid medicines. These medicines include diamorphine, morphine and pethidine. Opioids are usually given by your midwife injecting them into a large muscle in your arm or leg. The pain relief is often limited and side-effects include making you feel sick, dizzy or very sleepy. Opioid medicines can also make your baby feel sleepy and can sometimes temporarily reduce your baby's ability to breathe at birth.

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS). Four electrodes are placed on your back and electrical impulses are sent to your nerves to block the pain signal going from your uterus (womb) to your brain. You can change the strength of the electrical impulses to help control your pain. TENS is often used early in labour and may become less effective as labour progresses.

Availability and use of medicines may vary from country to country.

Preparing for an epidural

Your anaesthetist will discuss with you what will happen before, during and after your epidural, and any pain you might have. This is your opportunity to understand what will happen, and you can help yourself by preparing questions to ask about the risks, benefits and any alternatives to the procedure. This will help you to be informed, so you can give your consent for the procedure to go ahead, which you may be asked to do by signing a consent form.

An epidural isn't suitable for you if you have a blood-clotting problem. You must tell your midwife or anaesthetist if you're taking blood-thinning medicines, such as aspirin, warfarin or clopidogrel. An epidural may not be suitable for you if you have had an operation on your back. Ask your midwife or anaesthetist for more information.

Before your anaesthetist gives you an epidural, you will have a small tube (cannula) inserted into a vein in your hand or arm. You may have an intravenous drip set up too. These can be used to give you fluids and medicines that you may need during labour. Your blood pressure and pulse will be monitored while your anaesthetist is putting in the epidural and at any time when the dose is topped up. Your baby will be monitored too, to ensure that he or she is safe during the birth.

What happens during an epidural

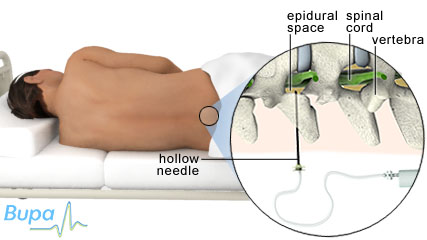

You will be asked either to lie on your side, with your knees drawn up to your abdomen and your chin tucked in, or to sit up on the bed and lean forward. Both positions open up the space between your vertebrae.

Where the epidural is positioned

The anaesthetist will carefully select a point to inject by feeling for specific bones in your spine and hips. He or she may mark this site with a pen to show where to insert the needle. Your anaesthetist will clean the skin on your back with a sterilising solution and give you an injection of local anaesthetic to the tissues in this area. He or she will also cover your back in a sterile drape, with a square hole around the site of the epidural.

When your skin is numb, your anaesthetist will pass a larger, hollow needle into the epidural space. When the needle reaches the correct spot, he or she will insert a fine plastic tube (catheter) through the centre of the needle. Your anaesthetist will then remove the needle and leave the catheter in place, running from the epidural space to outside of your body. The catheter is held in place with adhesive tape.

Your anaesthetist will use the catheter to inject local anaesthetic and/or other pain-relief medicines directly into the epidural space. After 15 to 20 minutes, your anaesthetist will confirm that the epidural is working by checking how sensitive your legs are to cold, such as with an ice cube, or using a pinprick.

Your anaesthetist may attach a pump to the catheter so that you can have a top-up as and when you need it. You may be allowed to control the pump yourself. This is called patient-controlled epidural analgesia or PCEA.

It's very important that you stay still while your anaesthetist is preparing the site for the epidural injection and especially while the epidural needle is being inserted. Any movement makes positioning the needle more difficult.

When you no longer need any pain relief, the catheter is carefully withdrawn and the area is covered with a plaster.

What to expect afterwards

After an epidural, you will need to rest until the effects of the anaesthetic have passed. You may not be able to feel or move your legs properly for several hours.

What are the risks?

Epidurals are commonly performed and generally safe. However, in order to make an informed decision and give your consent, you need to be aware of the possible side-effects and the risk of complications of this procedure.

Side-effects

These are the unwanted, but mostly temporary effects of having an epidural. Common side-effects are listed here.

- A drop in blood pressure. Your blood pressure will be checked regularly. If it drops, you may be given medicines to raise it back to normal.

- Loss of strength or control of your leg muscles. Your muscle strength will return with time after the epidural has been stopped.

- Difficulty passing urine. You may need to have a catheter fitted to drain urine from your bladder into a bag, until the effects of the epidural wear off.

- Itchy skin. This may happen with some medicines and your anaesthetist will change your medicine to deal with this.

Complications

This is when problems occur during or after the epidural. Most women aren't affected. With any procedure involving anaesthesia there is a very small risk of an unexpected reaction to the anaesthetic. Complications specific to an epidural are uncommon but can include the following.

- Headache. The epidural needle may puncture the membrane covering your spinal cord and fluid can leak out. This is called a dural puncture and it can cause headaches. This happens to about one in every 100 women. Headaches can last up to a week, or sometimes longer, and if they are severe you may need further treatment. You may need an epidural blood patch, which means that some of your blood is taken and injected near to the puncture where it will clot and seal the hole.

- Assisted birth. You may find it difficult to push. It's possible that your doctor may need to use forceps, a ventouse (vacuum extraction), or some similar assistance to help you to give birth.

- Infection in your back. This is very rare because your skin is cleaned before the sterile needle is inserted. It happens to two in 100,000 women. If you develop an infection, the catheter will be removed, the infected area would be drained and you would need to take antibiotics. If you develop a fever after you have returned home, contact the hospital or your doctor for advice because this could mean you have an infection.

- Long-term numbness. Rarely, you may have temporary patches of numbness, which happens to one in 1000 women. Permanent damage, such as paralysis (complete loss of sensation and movement), is extremely rare, happening to four in one million women.

As with every procedure, there are some risks associated with an epidural. The chances of these happening are specific to you and differ for every person. Ask your surgeon or anaesthetist to explain how these risks apply to you.

Produced by Louise Abbott, Bupa Health Information Team, April 2012.

Published by Bupa's Health Information Team, May 2010.

This section contains answers to common questions about this topic. Questions have been suggested by health professionals, website feedback and requests via email.

Can I still push if I have an epidural during childbirth?

Do I need to decide whether to have an epidural before I come to hospital, or can I decide as I'm giving birth?

Will an epidural affect my memory of the birth or stop me from holding my baby immediately after birth?

Will I be able to see what the surgeon is doing during a caesarean delivery under epidural anaesthesia?

Can I still push if I have an epidural during childbirth?

Yes, you can still push but the epidural will make it difficult for you to 'feel' when to push. The epidural may also affect how hard you can push.

Explanation

An epidural won’t stop you from pushing your baby out during delivery, but it will stop you feeling the urge to push. This means you may find it difficult to 'feel' when to push. The epidural may also affect how hard you can push. Because of this it may take longer for you to give birth. If your labour goes on for too long, it's possible you may become too tired to push.

Your midwife may suggest stopping the epidural when it’s time to push. Stopping the epidural will help you feel the urge to push but it also means you will begin to feel the pain of your contractions.

Your midwife or doctor may use forceps or a ventouse to help you give birth if you find it difficult to push hard. Forceps are like large tongs with curved ends that fit around your baby's head. Your doctor or midwife will pull gently on them while you push. A ventouse (vacuum extraction) uses suction. A cup is placed on your baby's head and attached to a vacuum machine. The air is sucked out which attaches the cup strongly to your baby's head. Your midwife or doctor then pulls on the cup as you push.

Further information

National Childbirth Trust

0300 330 0772

www.nct.org.uk

Sources

- Epidurals. The Birth Trauma Association. www.birthtraumaassociation.org.uk, accessed 1 March 2010

- Pain relief in labour. Obstetric Anaesthetists’ Association. www.oaa-anaes.ac.uk, published January 2008

Do I need to decide whether to have an epidural before I come to hospital, or can I decide as I'm giving birth?

It's a good idea to talk to your midwife and make a birth plan early on in your pregnancy.

Explanation

During your pregnancy you will have several check-ups with your midwife. It's a good idea to make a birth plan with your midwife early on in your pregnancy to help you decide how you would like your labour and birth to be managed and where you would like to give birth. The choices you make will influence whether an epidural is available when you give birth or not. For example, it's very unlikely that you will have access to an epidural if you have a home birth.

If you decide to have your baby in hospital, you will have a wider choice of pain-relief methods available to you. You can decide to have an epidural before coming into hospital, or if you’re opting to have a natural birth, you can change your mind at any time during labour and ask for an epidural.

It’s a good idea to discuss epidural pain relief with your midwife before you come into hospital. This gives you an opportunity to find out what services your hospital offers and you can ask your midwife to explain the benefits and risks of having an epidural.

Further information

National Childbirth Trust

0300 330 0722

www.nct.org.uk

Sources

- Pain relief in labour. Obstetric Anaesthetists’ Association. www.oaa-anaes.ac.uk, published January 2008

Will an epidural affect my memory of the birth or stop me from holding my baby immediately after birth?

No, an epidural won’t affect your memory or stop you from holding your baby after birth.

Explanation

An epidural involves injection of local anaesthetic and/or pain-relief medicines. These medicines will block pain in the lower part of your body, but shouldn’t affect your memory. Immediately after the birth, your baby will usually be handed to you so that you have skin-to-skin contact if you wish. You may also want to put your baby to your breast.

Further information

National Childbirth Trust

0300 330 0722

www.nct.org.uk

Emma's diary

www.emmasdiary.co.uk

Sources

- Info centre – Caesarean birth. National Childbirth Trust. www.nct.com, accessed 1 March 2010

Will I be able to see what the surgeon is doing during a caesarean delivery under epidural anaesthesia?

No, during the operation your abdominal (tummy) area is shielded from you, so you won't be able to see your surgeon perform the operation.

Explanation

If you have a caesarean delivery under epidural anaesthesia you will stay awake during the operation. You won't feel any pain from your waist down but you may feel some pushing or pulling during the operation.

You will be lying on your back during the operation. A raised sheet or shield is usually placed just below your breasts as a screen to hide your abdominal area from your view. Your surgeon will usually ask your birth partner to sit beside you at the top end of the table. This means your birth partner won't be able to see the operation either.

Your surgeon will make a cut through your abdomen and carefully remove your baby. Usually you will be able to see and hold your baby immediately after delivery. The raised sheet or shield will only be removed after your surgeon has closed your wound and dressed it.

Further information

National Childbirth Trust

0300 330 0772

www.nct.org.uk

Emma's diary

www.emmasdiary.co.uk

Sources

- Info centre – Caesarean birth. National Childbirth Trust. www.nct.com, accessed 1 March 2010

Related topics

Caesarean delivery

Giving birth vaginally

Local anaesthesia and sedation

This information was published by Bupa's Health Information Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been peer reviewed by Bupa doctors. The content is intended for general information only and does not replace the need for personal advice from a qualified health professional.

Publication date: May 2010.

Epidural for childbirth factsheet

Visit the epidural for childbirth health factsheet for more information.

Related topics

Caesarean delivery

Childbirth – vaginal delivery

Epidural for chronic back pain

Epidural for surgery and pain relief

General anaesthesia

Local anaesthesia and sedation

Further information

Obstetric Anaesthetists’ Association

www.oaa-anaes.ac.uk

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

www.rcog.org.uk

Sources

- Allman K, Wilson I. Oxford handbook of anaesthesia. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007

- Pain relief in labour. Obstetric Anaesthetists' Association. www.oaa-anaes.ac.uk, published January 2008

- Simmons S, Cyna A, Dennis A, et al. Combined spinal-epidural versus epidural analgesia in labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 3. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003401.pub2

- Blott M. The day-by-day pregnancy book. 1st ed. London: Dorling Kindersley; 2009

- Management of normal labor. The Merck Manuals. www.merckmanuals.com, published June 2007

- Pain relief options in labour. NCT. www.nct.org.uk, accessed 23 February 2012

- Intrapartum care: care of healthy women and their babies during childbirth. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), September 2007. www.nice.org.uk

- Hawkins J. Epidural analgesia for labor and delivery. N Engl J Med 2010; 362(16):1503–10. doi:10.1056/NEJMct0909254

- Labor and delivery, analgesia, regional and local. eMedicine. www.emedicine.medscape.com, published 9 May 2011

- Arulkumaran S, Symonds I, Fowlie A. Oxford handbook of obstetrics and gynaecology. 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004

- The Pregnancy Book 2009. Department of Health. www.dh.gov.uk, published 29 October 2009

- What happens during an elective or emergency caesarean section? NCT. www.nct.org.uk, accessed 23 February 2012

- Anim-Somuah M, Smyth R, Jones L. Epidural versus non-epidural or no analgesia in labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 12. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000331.pub3

- Anaesthesia explained. Royal College of Anaesthetists. www.rcoa.ac.uk, published May 2008

This information was published by Bupa's Health Information Team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been peer reviewed by Bupa doctors. The content is intended for general information only and does not replace the need for personal advice from a qualified health professional.