Heart block

Heart block causes your heartbeat to slow down or beat irregularly. It happens when the electrical signals that control your heartbeat are slowed down or blocked as they travel through your heart. Heart block is a type of arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat).

Animation – The different types of arrhythmia

About heart block

Symptoms of heart block

Complications of heart block

Causes of heart block

Diagnosis of heart block

Treatment of heart block

Animation – The different types of arrhythmia

The information on the video provided does not constitute advice on diagnosis or the treatment for heart disease and such advice should always be sought from a doctor or another suitably qualified health professional.

About heart block

Your heart is responsible for delivering the oxygen in your blood to your body, by pumping it through your blood vessels. When your heart beats too slowly, it can't do this as efficiently. The usual heart rate for adults is between 60 and 100 beats per minute. Your heartbeat is considered to be too slow if it drops below 50 beats per minute. This can lead to symptoms such as fainting and breathlessness.

What happens in heart block?

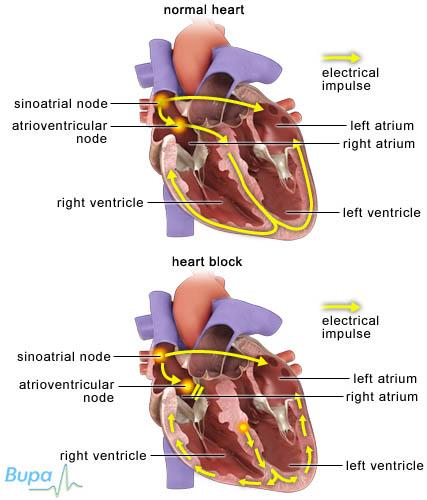

Your heartbeat is controlled by electrical signals (impulses) that travel through your heart to make it contract. These impulses start in a part of the heart wall called the sinus node. They then travel from the atria (the upper chambers of your heart) to the ventricles (the lower chambers) through an area called the atrioventricular (AV) node. The AV node helps to synchronise the pumping action of the atria and ventricles.

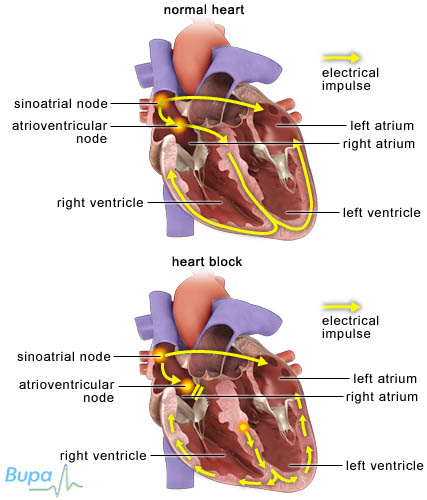

If you have heart block, it means there is a problem affecting how these electrical signals are transmitted through your heart. When the problem occurs at the AV node, it prevents the signals being conducted from the atria to the ventricles. This is called AV block. There are three different degrees of AV block, which are described below.

• First-degree – the electrical signals are slowed as they pass through the AV node. You will rarely have any symptoms.

• Second-degree – not all electrical signals reach your ventricles. The signals can sometimes become increasingly delayed until one is blocked altogether, or it may be that every other signal is blocked. This type of heart block may cause you symptoms such as dizziness and fainting, but you may not have any symptoms.

• Third-degree (complete heart block) – this is the most serious type of heart block. It's often found in adults who already have heart disease. It occurs when no electrical signals reach the ventricles from the atria and the ventricles end up producing their own electrical signals (called the escape rhythm). You will usually have a very slow heartbeat (bradycardia) and it can cause you to have blackouts.

Heart block can also occur in the specialised group of electrical-conducting muscle fibres (the bundle of His) that come out of the AV node, divide and lead into the right and left ventricles. This is called bundle branch block. It can affect the left- or right-hand side of your heart. If you have right bundle branch block, you probably won't have any symptoms. Left bundle branch block is more often the result of a heart problem, such as high blood pressure.

Symptoms of heart block

Whether or not you have any symptoms from heart block depends on the type of heart block you have and how severe it is. If the heart block has caused your heart rate to slow down (especially if it's less than 40 beats per minute), you may have:

• dizziness

• fainting or nearly fainting

• chest pain

• breathlessness following exercise or activity

These symptoms may be caused by problems other than heart block, but if you have them see a doctor for advice.

Complications of heart block

Most people who have heart block don't develop complications. However, it's possible for heart block to lead to heart failure or blackouts.

Causes of heart block

Causes of heart block include:

• older age – it mostly occurs in people over 65

• coronary artery disease

• certain medicines (including beta-blockers, digoxin, verapamil and amiodarone)

• diseases of the heart muscle, for example sarcoidosis

• certain infectious diseases (such as Lyme disease)

• some other diseases (such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus)

• congenital disorders (conditions you're born with)

Diagnosis of heart block

Heart block is often found by chance if you have tests for other problems. Your doctor will ask about your symptoms and examine you. He or she may also ask you about your medical history and do tests to find out if any underlying disease or condition, such as an underactive thyroid, is causing your symptoms.

Some medicines, such as beta-blockers, can slow down your heart rate. Your doctor will review any medicines that you're taking to make sure they're not causing your heart block.

Your doctor may refer you to a cardiologist for further tests. A cardiologist is a doctor specialising in conditions affecting the heart.

You may have the following tests to confirm your diagnosis.

• Blood tests – to check for underactive thyroid.

• Electrocardiogram (ECG) – measures the electrical activity in your heart to see how well it's working.

• Echocardiogram – uses ultrasound to produce a clear image of your heart muscles and valves.

• 24-hour heart monitor – to record your heart rate and rhythm.

• Tilt-table – to see whether or not a slow heart rate is triggered by a change in your posture (a condition known as postural hypotension or vasovagal syndrome).

Please note that availability and use of specific tests may vary from country to country.

Treatment of heart block

Treatment depends on how severe your heart block is. If your heart block is mild, was discovered by chance and you don't have any symptoms, you probably won't need any treatment.

If your heart block is caused by medicines you're taking, your doctor can review them. If it's caused by an underlying condition, that will be the focus of your treatment.

If your heart block is more severe, but not caused by medicines or an underlying condition, you will probably need to have a pacemaker fitted.

Pacemaker implantation

A pacemaker is a small device, about the size of a matchbox, usually implanted near your collarbone on the left side of your chest. It monitors your heartbeat and produces electrical signals to stimulate your heart to contract. A pacemaker sends out signals only when your heartbeat slows.

The pacemaker is connected to your heart by one or more leads, which are passed through a vein to your heart. For heart block, pacemakers with two leads (called dual-chamber pacemakers) are normally used. The two leads connect to two different points in your heart – usually your right atrium and right ventricle.

If your doctor thinks you need a pacemaker urgently – because of the risks of having a low heart rate – you may have a temporary pacemaker put in until you're able to have a permanent one fitted. This involves threading a wire into your heart, starting from a vein in your groin or neck.

You will probably have your pacemaker fitted under local anaesthesia and sedation. This means all feeling from the area where the pacemaker is put in will be blocked and you will feel relaxed, but stay awake during the procedure.

You may be able to go home the day after your procedure, once your doctor has checked that the pacemaker is working correctly. It usually takes about six weeks for your wound to heal and you may be given an appointment during this time to have your stitches removed. However, this varies between individuals and with the technique used to fit your pacemaker, so it's important to follow your doctor's advice.

Details of the procedure may vary from country to country.

Produced by Krysta Munford, Bupa Health Information Team, July 2012.

Answers to questions about heart block

Does having a slow heart rate mean I have a heart block?

Can heart block cause black-outs?

Will I be able to feel the pacemaker?

Can I exercise or play sports with a pacemaker?

How long will my pacemaker last?

Does having a slow heart rate mean I have a heart block?

No, there are many other factors that can cause a slow heart rate (bradycardia). Many physically active people have hearts that beat more slowly than usual, and this doesn’t mean that there’s anything wrong with their heart.

Explanation

Many athletes or people who are physically fit have hearts that beat more slowly than usual. This is perfectly normal for them. It’s called sinus bradycardia and can also happen during a state of deep relaxation. However, an unusually slow heartbeat can be caused by:

• a heart attack

• certain medicines

• jaundice

• hypothermia (when your body temperature drops too low)

• an under active thyroid (hypothyroidism)

• a rise in the pressure inside your brain

Another condition that can slow heart rate is sick sinus syndrome. This happens when the heart’s natural pacemaker (the sinus node) doesn’t work properly. It causes a slow heartbeat, or fast heartbeat or a heartbeat that swaps between the two, making you feel dizzy, tired and weak.

This condition is more common in elderly people, and is associated with:

• a heart attack

• heart surgery

• taking certain medicines (such as beta-blockers, digoxin, verapamil and amiodarone)

Further information

• Arrhythmia Alliance

01789 450787

www.heartrhythmcharity.org.uk

• The British Heart Foundation

0300 330 3311

www.bhf.org.uk

Sources

• Bradycardia. Arrhythmia Alliance. www.heartrhythmcharity.org.uk, accessed 15 March 2010

• Costa DD, Brady WJ, Edhouse J. Bradycardias and atrioventricular conduction block. BMJ 2002; 324:535–38

Can heart block cause black-outs?

Heart block can sometimes cause a brief black-out (fainting). This happens if your heart rate becomes so slow, that it temporarily stops altogether. This is sometimes called a Stokes–Adams attack.

Explanation

If your heart rate slows down and temporarily stops, not enough blood is able to reach the brain. This causes the black-out. Immediately before having the black-out, you may look pale and your pulse will be very slow, but you will carry on breathing. During the attack, you may have a convulsion (the legs may twitch around). Sometimes Stokes–Adams attacks can be fatal, but usually they last about 30 seconds and then you recover fully. You may look flushed immediately after the attack.

Black-outs can happen for other reasons, so it’s important to visit your GP for advice.

Further information

• Arrhythmia Alliance

01789 450787

www.heartrhythmcharity.org.uk

• The British Heart Foundation

0300 330 3311

www.bhf.org.uk

Sources

• Bradycardia. Arrhythmia Alliance. www.heartrhythmcharity.org.uk, accessed 15 March 2010

• Costa DD, Brady WJ, Edhouse J. Bradycardias and atrioventricular conduction block. BMJ 2002; 324:535–38

• Heart block. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. www.cks.nhs.uk, accessed 15 March 2010

Will I be able to feel the pacemaker?

You may be aware of the pacemaker at first and it may feel uncomfortable to lie in certain positions; however you will quickly get used to it. You probably won’t be aware of the pacemaker’s effects on your heart.

Explanation

A pacemaker is so small that it can easily be hidden inside the chest. You may be able to feel the pacemaker box and connecting leads under your skin as the wound heals – it’s very important that you don’t try to move them. Let your doctor know if they continue to bother you.

Your pacemaker will be programmed while you’re in hospital to the best settings for you, so you shouldn’t be aware of it working. However, if your heartbeat was slow before it was fitted, then you may notice your heart beating faster.

Further information

• Arrhythmia Alliance

01789 450787

www.heartrhythmcharity.org.uk

• The British Heart Foundation

0300 330 3311

www.bhf.org.uk

Sources

• Pacemakers. British Heart Foundation. www.bhf.org.uk, accessed 15 March 2010

• Pacemaker information. Arrhythmia Alliance. www.heartrhythmcharity.org.uk, accessed 15 March 2010

Can I exercise or play sports with a pacemaker?

You will be able to carry out exercise and most sports as normal when you have fully recovered from the procedure. However, you shouldn’t do contact sports.

Explanation

You will probably be advised not to do any strenuous activity until after your pacemaker follow-up appointment. This is about six weeks after having the pacemaker fitted.

After your follow-up appointment, your doctor may advise that you increase your level of activity and start to exercise or play sports as normal.

You may want to wear a protective pad over the pacemaker site so that the device doesn’t get damaged or knocked.

You doctor may advise you not to do:

• contact sports such as football or rugby

• heavy lifting

• rifle shooting – because of the kickback

urther information

• Arrhythmia Alliance

01789 450787

www.heartrhythmcharity.org.uk

• The British Heart Foundation

0300 330 3311

www.bhf.org.uk

Sources

• Pacemakers. British Heart Foundation. www.bhf.org.uk, accessed 15 March 2010

• Pacemaker information. Arrhythmia Alliance. www.heartrhythmcharity.org.uk, accessed 15 March 2010

How long will my pacemaker last?

A pacemaker battery normally lasts between six and 10 years. You will have regular check-ups to predict when you will need a new one. It won’t be allowed to completely run down.

Explanation

You will usually have check-ups every three to 12 months depending on the type of pacemaker you have fitted and how well it’s working. If there are any problems with your pacemaker, arrangements will be made for you to have a pacemaker box change.

Most of the pacemaker box is taken up with the battery, so the whole box is replaced when the battery shows signs of wear. The leads of the pacemaker are usually left in place. This is a minor procedure, and is usually done under a local anaesthesia.

Further information

• Arrhythmia Alliance

01789 450787

www.heartrhythmcharity.org.uk

• The British Heart Foundation

0300.330 3311

www.bhf.org.uk

Sources

• Pacemakers. British Heart Foundation. www.bhf.org.uk, accessed 15 March 2010

• Pacemaker information. Arrhythmia Alliance. www.heartrhythmcharity.org.uk, accessed 15 March 2010

Related topics

• Arrhythmia

• Cardiovascular system

• Electrocardiogram (ECG)

Heart block factsheet

Visit the heart block health factsheet for more information.

Related topics

• Arrhythmia

• Cardiovascular system

• Electrocardiogram (ECG)

Further information

• Arrhythmia Alliance

01789 450787

www.heartrhythmcharity.org.uk

• The British Heart Foundation

0300 330 3311

www.bhf.org.uk

Sources

- Bradycardia classification. BMJ Best Practice. www.bestpractice.bmj.com, published 28 March 2012

- Camm A, Luscher T, Serruys PW (editors). The ESC textbook of cardiovascular medicine. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009:984–85

- Dual-chamber pacemakers for symptomatic bradycardia due to sick sinus syndrome and/or atrioventricular block. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), February 2005. www.nice.org.uk

- First-degree atrioventricular block clinical presentation. eMedicine. www.emedicine.medscape.com, published 29 June 2011

- Second-degree atrioventricular block clinical presentation. eMedicine. www.emedicine.medscape.com, published 16 September 2011

- Atrioventricular block history and examination. BMJ Best Practice. www.bestpractice.bmj.com, published 15 March 2012

- Third-degree atrioventricular block clinical presentation. eMedicine. www.emedicine.medscape.com, published 16 September 2011

- Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary. 63rd ed. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain; 2012

- Pacemakers. British Heart Foundation. www.bhf.org.uk, published 1 April 2012

- Pacemakers and implantable cardioverter defibrillators. eMedicine. www.emedicine.medscape.com, published 9 May 2011

- Sinus bradycardia. eMedicine. www.emedicine.medscape.com, published 22 December 2012

- Syncope. eMedicine. www.emedicine.medscape.com, published 11 August 2011

- Pacemaker. Arrhythmia Alliance. www.arrhythmiaalliance.org, published April 2010

- Pacemakers and implantable cardioverter defibrillators. eMedicine. www.emedicine.medscape.com, published 9 May 2011

- Get active, stay active. Brisith Heart Foundation. www.bhf.org.uk, published 2012