Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT)

Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) is when your heart beats too fast, usually at a rate of about 130 to 250 beats per minute. SVT is a type of arrhythmia (abnormal heart rhythm). It's caused by faulty electrical signals in your heart and often affects young, healthy people.

Animation – The different types of arrhythmia

About SVT

Symptoms of SVT

Complications of SVT

Causes of SVT

Diagnosis of SVT

Treatment of SVT

The different types of arrhythmia

The information on the video provided does not constitute advice on diagnosis or the treatment for heart disease and such advice should always be sought from a doctor or another suitably qualified health professional.

About SVT

Tachycardia means a rapid heart rate of more than 100 beats per minute. Supraventricular means that the problem starts in the upper part of your heart (above the ventricles).

SVT episodes are often temporary and frequently go away on their own without any treatment. They often happen in young, healthy people. Episodes often become less frequent as you get older, but you may find they get worse. Episodes vary in how long they last, from a few seconds or minutes, or up to several hours.

What happens during SVT?

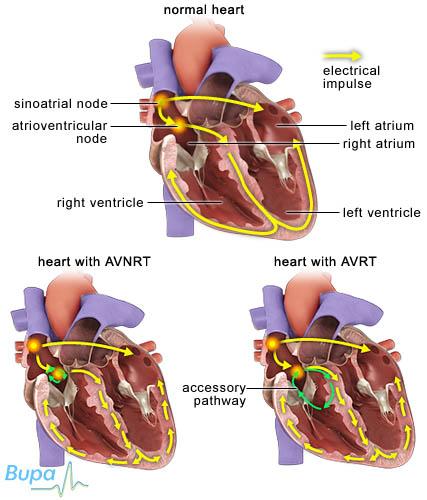

Your heartbeat is controlled by electrical signals (impulses), which start in a part of your heart's muscular wall, called the sinus node, and travel through your heart making it contract. The signals travel from the atria (the upper chambers of your heart) to the ventricles (the lower chambers of your heart) through an area called the atrioventricular (AV) node. The AV node helps to synchronise the pumping action of the atria and ventricles.

SVT most often occurs when there is an extra electrical pathway in your heart between your atria and your ventricles. This allows electrical signals to 'short-circuit' and re-enter the atria. The signals end up travelling around your heart in a circle. These types of SVT are referred to as re-entrant tachycardias or paroxysmal SVT. This means symptoms come on suddenly and are temporary.

Types of supraventricular tachycardia

There are three main types of SVT, which are described below and in the illustration.

- If the extra pathway is located in your AV node, it's called atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia (AVNRT).

- If the extra pathway connects your atria and ventricles separately from the AV node, it's called atrioventricular re-entrant tachycardia (AVRT).

- If the SVT arises from the atrial tissue in an area other than your sinus node, it's called atrial tachycardia (a less common type of SVT).

Symptoms of SVT

You may or may not have symptoms of SVT. You're more likely to have symptoms if you already have heart disease.

The symptoms you experience during an attack of SVT may include:

- palpitations – you're aware of your heart suddenly beating faster

- shortness of breath

- chest pain

- dizziness and fainting (although this is rare)

These symptoms may be caused by problems other than SVT. If you have any of these symptoms, see a doctor for advice.

Complications of SVT

Your heart may not be able to pump blood effectively around your body because your heart rate is abnormal. This can result in low blood pressure, which may cause fainting. Low blood pressure may also result in less blood flowing to your heart (ischaemia), which can damage your heart muscle, causing your heart to pump less effectively. This may result in heart failure. These complications are more common if you have other problems with your heart, such as valve disease.

You also have a small risk of sudden death, but usually only if you have a particular type of SVT called Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome.

Causes of SVT

The cause of SVT isn't fully understood at present. Episodes often come on without warning and you may develop SVT without having any underlying cause or risk factor.

However, certain factors may lead to SVT developing, including:

- certain medicines

- problems with your heart since birth (congenital heart disease)

- emotional or physical stress

- hormonal changes

- alcohol

- caffeine

- smoking

- taking illegal drugs, such as cocaine or ecstasy

Diagnosis of SVT

Your doctor will ask about your symptoms and examine you. He or she may check your blood pressure, listen to your heartbeat and take your pulse. You may also have a test called an electrocardiogram (ECG). An ECG records the electrical activity of your heart to see what your heart rhythm is.

If your doctor suspects that you have SVT, he or she may refer you to a cardiologist, a doctor specialising in heart conditions. You may have other tests, including:

- blood tests

- echocardiogram – an ultrasound scan of your heart that provides a clear image of your heart muscles and valves, and shows how well your heart is working

- ambulatory ECG – this takes a recording of your heartbeat while you go about your usual daily activities, over 24 hours or longer

- implantable loop recorder – this is placed under your skin so that it can take a recording of your heartbeat over a much longer period

- electrophysiological study – this uses electrode catheters to stimulate the heart, allowing your doctor to check your heart's electrical activity in greater detail than an ECG

Please note that availability and use of specific tests may vary from country to country.

Treatment of SVT

There are many treatments available for SVT. Your treatment will depend on your symptoms. Your doctor will discuss your treatment options with you.

The aim of treatment is to control your heart rhythm and rate, and reduce your risk of heart failure. You may not need any treatment at all, especially if your symptoms are mild.

Self-help

Your doctor may advise you on things you can do to stop an episode. You can try any of the options below when you feel an SVT episode starting.

- Valsalva manoeuvre. This involves breathing in and then straining out (as if having a bowel movement) while holding your breath – sit or lie down first because this could cause you to faint.

- Diving reflex. Fully immerse your face in cold water or suck on ice cubes.

- Change position. Bend over or lie down.

- Hold your breath or cough.

Your doctor may suggest you improve your heart health by:

- reducing your alcohol and caffeine intake

- stopping smoking, if you smoke

- doing 150 minutes (two and a half hours) of moderate exercise a week in bouts of 10 minutes or more

Physical therapies

Applying pressure to an artery in your neck may help to stop your heart beating rapidly. However, this must only be done by a doctor. It can be dangerous to do on some people and your doctor will need to check whether you're suitable for this technique.

Emergency treatments

Emergency treatments for SVT may include:

- electrical (DC) cardioversion – this uses an electric shock to restore your rapid heartbeat back to normal

- medicines given through a drip into your bloodstream, such as adenosine and verapamil

Medicines

If your symptoms come on suddenly, you may be given anti-arrhythmic medicines, either as tablets or given through a drip into your bloodstream, to try to get your heart rhythm back to normal (this is called pharmacological or medical cardioversion). This is usually tried within 48 hours of having symptoms. If this type of medicine is not successful, you may have DC cardioversion to restore your normal heart rate.

There are several different types of medicine that can help control your heart rate and rhythm, including beta-blockers, calcium-channel blockers and anti-arrhythmic medicines. You often take them to prevent further SVT attacks.

Always ask your doctor for advice and read the patient information leaflet that comes with your medicine.

Availability and use of medicines may vary from country to country.

Surgery

Surgery is only used when your symptoms haven't responded very well to other treatments. Your doctor may advise you to have a procedure called catheter ablation if your attacks require regular medication. Small tubes called electrode catheters are passed into the veins in your groin and threaded up to your heart. Any tissue that is disrupting or causing abnormal electrical signals in your heart is burnt or frozen to destroy it.

Availability and use of different treatments may vary from country to country. Ask your doctor for advice on your treatment options.

Produced by Alice Rossiter, Bupa Health Information Team, August 2012.

What is Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome?

How long does it take to recover from catheter ablation?

What is sinus tachycardia?

What is Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome?

Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome is caused by an unusual connection between the atria and ventricles (upper and lower chambers of the heart). This puts you at risk of having supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) and atrial fibrillation.

Explanation

Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome happens when the upper and lower chambers of the heart don’t separate properly when a baby is developing in the womb. This leads to an unusual connection forming between the atria and the ventricles, called an accessory pathway.

In a normal heart, the electrical impulses travel only in one direction, from the upper to the lower chambers through a junction box called the atrioventricular (AV) node. However, in Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, the accessory pathway creates a circuit, allowing the impulses to travel back up to the atria, and activate them before the next heartbeat. This results in symptoms of SVT.

If you have Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, you may have symptoms of SVT. However, you may not even know you have a problem unless it happens to show up on an ECG.

Wolff-Parkinson-White can be treated with anti-arrhythmic medicines or with a procedure called catheter ablation.

Further information

-

Arrhythmia Alliance

01789 450787

www.heartrhythmcharity.org.uk

Sources

- Esberger D, Jones S, Morris F. ABC of clinical electrocardiography: Junctional tachycardias. BMJ 2002; 324:662–65; doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7338.662 www.bmj.com, accessed 7 April 2010

- Heart rhythms booklet. Supraventricular tachycardia. British Heart Foundation. www.bhf.org.uk, accessed 7 April 2010

- Supraventricular tachycardia. Arrhythmia Alliance. www.heartrhythmcharity.org.uk, accessed 7 April 2010

How long does it take to recover from catheter ablation?

Most people recover quickly from catheter ablation, usually within a day or two after having the procedure.

Explanation

Catheter ablation is a minimally invasive procedure, which means it involves making only a small puncture in your groin. The procedure is done under local anaesthetic and sedation. The anaesthetic completely blocks pain from the groin area and the sedative helps you to feel relaxed during the procedure, without putting you to sleep. You should be able to go home on the same day as the procedure, or the day after.

You may feel fleeting pains in the chest, shoulder, or neck, during the first few weeks. These are caused by the scarring process.

You will usually need to take it easy for a few days after the procedure. You shouldn’t do any heavy lifting or driving for at least two weeks.

Catheter ablation is a complex procedure and you may need a repeat procedure to successfully treat your symptoms.

Further information

-

Arrhythmia Alliance

01789 450787

www.heartrhythmcharity.org.uk

Sources

- Catheter ablation. Arrhythmia Alliance. Arrhythmia Alliance. www.heartrhythmcharity.org.uk, accessed 7 April 2010

- Heart rhythms booklet. Supraventricular tachycardia. British Heart Foundation. www.bhf.org.uk, accessed 7 April 2010

- At a glance guide to the current medical standards of fitness to drive. Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA). www.dft.gov.uk, February 2010

What is sinus tachycardia?

Sinus tachycardia means your heart is beating in a normal, regular rhythm, but too fast (above 100 beats per minute). It’s not related to supraventricular tachycardia.

Explanation

Your heart can beat faster or slower than normal at times. Factors that can speed up your heart rate, include:

- physical activity

- fear and/or panic

- fever

- pregnancy

- certain medicines

- illegal drugs

- caffeine, alcohol and nicotine

- more rarely, certain medical conditions such as an overactive thyroid gland, severe anaemia or pulmonary embolism

Most people don’t need treatment for sinus tachycardia. However, if it’s caused by an underlying condition, then your doctor will treat the condition.

Further information

-

The British Heart Foundation

0300 330 3311

www.bhf.org.uk

Source

- Heart rhythms booklet. Supraventricular tachycardia. British Heart Foundation. www.bhf.org.uk, accessed 7 April 2010

Related topics

- Arrhythmia

- Atrial fibrillation

- Cardioversion

- Electrocardiogram (ECG)

- Ventricular tachycardia

Further information

-

Arrhythmia Alliance

01789 450787

www.heartrhythmcharity.org.uk

-

The British Heart Foundation

0300 330 3311

www.bhf.org.uk

Sources

- Camm A, Luscher T, Serruys PW. The ESC textbook of cardiovascular medicine. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009: 1018

- Heart rhythms. British Heart Foundation. www.bhf.org.uk, published May 2009

- Tachycardia. American Heart Association. www.heart.org, published 5 April 2012

- Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia. eMedicine. www.emedicine.medscape.com, published 23 January 2012

- Blomström-Lundqvist C, Scheinman MM, Aliot EM, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 42(8): 1493–531

- Simon C, Everitt H, Kendrick T. Oxford handbook of general practice. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010: 276–77

- Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT). Pudmed Health. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. May 2010

- Physiological manoeuvres to stop SVTs. Arrhythmia Alliance. www.heartrhythmcharity.org.uk, published 2009

- Treatment options. Arrhythmia Alliance. www.arrhythmiaalliance.org.uk, accessed 22 May 2012

- Start active, stay active: a report on physical activity from the four home countries’ Chief Medical Officers. Department of Health. www.dh.gov.uk, published 2011

- Ventricular tachycardia treatment and management. eMedicine. www.emedicine.medscape.com, published 9 November 2011

- Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary. 62nd ed. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain; 2011

- Cardioversion. British Heart Foundation. www.bhf.org.uk, accessed 10 May 2012

- Catheter ablation. Arrhythmia Alliance. www.arrhythmiaalliance.org.uk, published April 2010

- Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2006. www.nice.org.uk

- Thoracoscopic epicardial radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2009. www.nice.org.uk

- Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. BMJ Best Practice. www.bestpractice.bmj.com, published 31 October 2011

- Assessment of tachycardia summary. BMJ Best Practice. www.bestpractice.bmj.com, published 26 September 2011

- Palpitations – management. Prodigy. www.prodigy.clarity.co.uk, published March 2009