Peptic ulcers

Published by Bupa's health information team, October 2009.

This factsheet is for people who have a peptic ulcer, or who would like information about it.

A peptic ulcer is an area of damage to the lining of either the stomach or the wall of the small bowel.

About peptic ulcers

Symptoms of peptic ulcers

Complications of peptic ulcers

Causes of peptic ulcers

Diagnosis of peptic ulcers

Treatment of peptic ulcers

About peptic ulcers

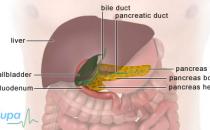

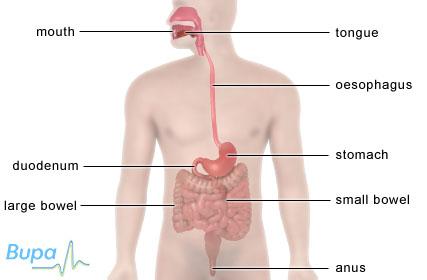

Your stomach produces acid to help you digest food. The lining of your stomach and first part of your small bowel (duodenum) have a layer of mucus that protects them from the acid. If this protection mechanism doesn’t work properly, the acid can eat into your stomach lining and cause an ulcer.

Stomach (gastric) ulcers and small bowel (duodenal) ulcers are collectively known as peptic ulcers. Duodenal ulcers are more common.

Stomach ulcers usually affect people between the ages of 40 and 80, and duodenal ulcers affect people aged 20 to 60. Peptic ulcers are more common in women than men.

The size of peptic ulcers can vary from one millimetre to several centimetres across. They look similar to mouth ulcers.

Symptoms of peptic ulcers

You may not have any symptoms at all. However, many people have pain in their abdomen (tummy), usually just below the breastbone (sternum). This pain is often described as burning or gnawing and may extend to your back. It usually comes on after eating – 15 to 20 minutes after eating if you have a stomach ulcer and one to three hours after a meal if the ulcer is in your small bowel. The pain may also wake you at night.

Other symptoms may include:

- heartburn

- a bitter taste in your mouth

- feeling sick or vomiting

- regurgitating food

It’s important to see your GP if you have:

- difficulty swallowing food

- lost weight without dieting

- seen blood in your vomit or bowel movements

- sudden, very painful abdominal pain

These symptoms may be caused by problems other than a peptic ulcer. If you have any of them, visit your GP for advice.

Complications of peptic ulcers

Most people who have a peptic ulcer don't have any complications. However, possible complications include the following.

Bleeding

Occasionally ulcers can cause the lining of your stomach or small bowel to bleed. If this happens suddenly, symptoms may include:

- vomiting blood – it may be bright red or like coffee grains (dark brown bits of clotted blood)

- dark faeces that look black or like tar – this is because the blood from the bleeding ulcer will have been partially broken down as it makes its way through the bowel

If you have any of these symptoms, see your GP immediately.

Anaemia

If the bleeding from the ulcer is slow, you might not see blood in your vomit or faeces. However, you may develop anaemia. Anaemia is when there are too few red blood cells or not enough haemoglobin in the blood.

Perforation

Rarely, the ulcer may eat very deeply into the wall of your stomach or small bowel making a hole into your abdomen. This is called perforation – it causes severe pain and you will need emergency surgery. However, because treatment with medicine is usually successful, it’s very unlikely that you will need surgery for a peptic ulcer.

Pyloric stenosis

Pyloric stenosis can result if you have a peptic ulcer that causes long-term inflammation in the lining of your stomach or small bowel. This is a narrowing of the small passage called the pylorus that links your stomach and the first part of your small bowel. The main symptom of pyloric stenosis is vomiting.

Causes of peptic ulcers

The most common cause of peptic ulcers is a stomach infection caused by a bacterium called Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori). This infection is quite common – about half of the world's population is infected with the bacterium but it doesn’t always cause illness.

H. pylori can cause inflammation in the lining of the stomach. Inflammation is when part of the body reacts to an infection or injury causing it to become swollen, hot, red and/or painful. The inflammation reduces the layer of mucus that protects the stomach and small bowel from the stomach acid and causes an ulcer. If the H. Pylori infection is in the upper part of your stomach, it can cause more acid to be produced. This can overload the protective layer of mucus and cause an ulcer.

The second most common cause of peptic ulcers is a type of medicine called non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Examples of these medicines include aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen and diclofenac. Most people can take these safely but sometimes if you take NSAIDs over a long period of time, they can damage the mucus lining in your stomach and cause a peptic ulcer. If you’re in doubt which painkillers to take, ask your pharmacist.

You’re more likely to get peptic ulcers if you smoke. You may also be more at risk if other people in your family have had ulcers.

It used to be thought that stress could cause a peptic ulcer. However, stress is now only considered to be important if it’s a result of a major operation or trauma.

Diagnosis of peptic ulcers

Your GP will ask about your symptoms and examine you. He or she may also ask you about your medical history. If your GP thinks you may have a peptic ulcer, he or she may recommend some of the following tests to diagnose you and decide what treatment will suit you best.

H. pylori test

As H. pylori is the most common cause of a peptic ulcer, your GP may test you for the bacterium and, if necessary, prescribe medicines to treat the infection.

H. pylori can be detected in a urea breath test. You will be asked to swallow a liquid containing a substance called urea that is broken down by H. pylori to produce water and carbon dioxide. Your breath will then be tested using a machine for the amount of carbon dioxide in it. If the carbon dioxide is over a certain level, H. pylori is present.

Alternatively a sample of your blood or your faeces will be sent to a laboratory to test for H. pylori.

Endoscopy

If you have a suspected peptic ulcer, your GP may arrange a gastro-intestinal endoscopy (also called a gastroscopy). Not everyone who has abdominal pain needs one, so your GP may use one of the other tests first. However, endoscopy is the only way to be certain whether or not you have a peptic ulcer.

An endoscopy is a procedure that allows a doctor to look at the inside of your body. The test is done using a narrow, flexible, tube-like telescopic camera called an endoscope that is passed through your mouth and into your stomach. The procedure usually lasts a few minutes.

Your doctor will be able to see the lining of your stomach and can take a sample of your stomach lining at the same time. This sample is either sent to a laboratory and examined under a microscope, or directly tested for H. pylori.

Treatment of peptic ulcers

Self-help

There are lifestyle changes that you can make to help your ulcers heal and prevent them coming back. These include:

- not having food and drink that give you more severe symptoms, such as spicy foods and alcohol

- stopping smoking

- not taking painkillers that are likely to cause ulcers in the future – your GP or pharmacist can give you advice on other medicines you can take instead

Medicines

There are two main groups of medicines available to treat peptic ulcers. These are:

- proton pump inhibitors, such as omeprazole and lansoprazole

- H2-blockers – examples include ranitidine and cimetidine

Both types of medicine reduce acid production in the stomach, allowing your ulcer to heal. They can both be used long-term to prevent your ulcer coming back.

These medicines will relieve your symptoms and within a few weeks your ulcer will heal. However, once you stop taking the medicine, your ulcer may come back unless the H. pylori has been treated and removed.

Treating H. pylori infection

If tests confirm that you have H. pylori, you will be prescribed medicines to treat it. This is usually a combination of a proton pump inhibitor and two antibiotics. Treating the H. pylori infection should allow your ulcer to heal and prevent it from coming back. Your GP will do the tests again after treatment to make sure it has been successful in getting rid of H. pylori.

Published by Bupa's health information team, October 2009.

This section contains answers to common questions about this topic. Questions have been suggested by health professionals, website feedback and requests via email.

Do I need to make any changes to what I eat if I have a peptic ulcer?

Where does Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) come from?

How long will it take before peptic ulcers improve?

Do I need to make any changes to what I eat if I have a peptic ulcer?

Answer

There are certain foods and drinks that can make your symptoms worse if you have a peptic ulcer.

Explanation

Your stomach produces acid to help with digestion. Too much acid can damage the lining of your stomach and first part of your small bowel (duodenum) and cause peptic ulcers. Foods that encourage acid production will usually make the symptoms of peptic ulcers worse. These include spicy foods, alcohol, fizzy drinks and citrus foods.

If you’re diagnosed with a peptic ulcer or regularly get heartburn or pain in your upper abdomen (tummy) after meals, it's important that you make some changes to your diet to help reduce your symptoms. These measures include:

- not having food and drink that give you more severe symptoms

- not eating fried or fatty foods

- not eating three hours before bedtime

- eating smaller meals

- eating meals that are high in fibre

- stopping smoking

Sources

- Dyspepsia – proven peptic ulcer. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. www.cks.library.nhs.uk, accessed 11 June 2009

- Peptic ulcer. GP Notebook. www.gpnotebook.co.uk, accessed 11 June 2009

- Dyspepsia: managing dyspepsia in adults in primary care. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), August 2004. www.nice.org.uk

Where does Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) come from?

Answer

It isn't known where H. pylori comes from, how it's spread or why some people become ill from it and others don't. It probably spreads from one person to another through close contact in early childhood or through poor hygiene. It's possible that contaminated food and water may cause infection.

Explanation

H. pylori infection is quite common – about half of the world's population is infected. These bacteria cause the stomach to make too much acid. The acid damages the lining of the stomach and small bowel (duodenum) and causes peptic ulcers. H. pylori is the main cause of peptic ulcers.

If you’re diagnosed with a peptic ulcer, your GP may recommend you have certain tests to find out if you have H. pylori. If you do, your GP may prescribe antibiotics to treat the infection. It's important that you take the full course of antibiotic treatment to make sure that you completely get rid of the bacteria from your digestive system.

Sources

- Dyspepsia – proven peptic ulcer. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. www.cks.library.nhs.uk, accessed 11 June 2009

- Peptic ulcers explained. Core. www.corecharity.org.uk, accessed 11 June 2009

- Helicobacter pylori. Health Protection Agency. www.hpa.org.uk, accessed 11 June 2009

How long will it take before peptic ulcers improve?

Answer

How soon you recover from a peptic ulcer depends on the size of the ulcer and its cause. You’re very likely to need to take medicines to relieve your symptoms. It can take several weeks for your ulcer to heal after the cause has been identified and treated.

Explanation

The main goals for treating a peptic ulcer include:

- removing the underlying cause (particularly H. pylori infection or use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, NSAIDs)

- preventing further damage and complications

- reducing the risk of the ulcer coming back

Medicines are usually needed to provide relief from your symptoms and to treat H. pylori infection. Lifestyle factors such as making changes to your diet are also important.

Once the cause of your peptic ulcer has been identified and treated, it may still take several weeks for it to heal. To help reduce the risk of it coming back, it's important that you follow your GP’s advice and complete the full course of any treatment you’re prescribed.

Sources

- Dyspepsia – proven peptic ulcer. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. www.cks.library.nhs.uk, accessed 11 June 2009

- Peptic ulcer. GP Notebook. www.gpnotebook.co.uk, accessed 11 June 2009

- Dyspepsia: managing dyspepsia in adults in primary care. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), August 2004. www.nice.org.uk

- Joint Formulary Committee, British National Formulary. 57th ed. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 2009.

- Helicobacter pylori. Health Protection Agency. www.hpa.org.uk, accessed 11 June 2009

Related topics

- Peptic ulcers

- Gastroscopy

- Giving up smoking

- Healthy eating

- Indigestion

- Indigestion medicines

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

This information was published by Bupa's health information team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been peer reviewed by Bupa doctors. The content is intended for general information only and does not replace the need for personal advice from a qualified health professional.

Related topics

- Gastroscopy

- Giving up smoking

- Indigestion

- Indigestion medicines

- Iron-deficiency anaemia

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

Further information

Core

020 7486 0341

www.corecharity.org.uk

Sources

- Dyspepsia – proven peptic ulcer. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. www.cks.library.nhs.uk, accessed 11 June 2009

- Peptic ulcer. GP Notebook. www.gpnotebook.co.uk, accessed 11 June 2009

- Peptic ulcers explained. Core. www.corecharity.org.uk, accessed 11 June 2009

- Helicobacter pylori infection. BMJ Clinical Evidence. www.clinicalevidence.com, accessed 11 June 2009

- Helicobacter pylori. World Health Organization. www.who.int, accessed 11 June 2009

- Joint Formulary Committee, British National Formulary. 57th ed. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 2009.

- Dyspepsia: managing dyspepsia in adults in primary care. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), August 2004. www.nice.org.uk

Publication date: October 2009.