Rubella (German measles)

Rubella (German measles) is a mild viral infection, but it can cause serious complications and birth defects in unborn babies if the mother gets the infection in pregnancy.

About rubella

Symptoms of rubella

Complications of rubella

Causes of rubella

Diagnosis of rubella

Treatment of rubella

Rubella and pregnancy

Prevention of rubella

About rubella

Rubella is an infectious disease caused by a virus. It usually causes a mild illness similar to a mild attack of measles, but it can cause serious harm to the unborn baby if you get the infection in pregnancy.

Since its introduction in 1988, the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine has helped reduce the number of babies born with congenital rubella syndrome. There haven’t been any outbreaks of rubella in recent years, but fewer children have been given the vaccine since 1997, when controversy surrounded the MMR vaccine. There is now an increased risk of getting rubella if you haven’t been immunised.

Symptoms of rubella

Symptoms of rubella may not start until two to three weeks after getting the infection. Symptoms are usually very mild and about four in 10 people with rubella don’t even notice that they have the infection. Symptoms of rubella may include the following.

- Pink itchy rash – this usually starts behind the ears and then spreads to the face and neck and upper body. The rash may last three to five days.

- Swollen glands (lymph nodes) – swelling around the ears, neck and the back of the head. It may be painful and start before the rash and last up to two weeks after the rash has gone.

- A high temperature – you may have a fever lasting several days.

- Cold-like symptoms – such as a runny nose, watery eyes and a sore throat.

Symptoms of rubella can last 10 days.

Complications of rubella

Rubella can cause serious harm to your unborn baby if you get the infection in pregnancy. Complications of rubella in pregnancy include:

-

miscarriage – this can occur in two out of 10 women in the first three months of pregnancy (first trimester)

- birth defects – if you get rubella in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy it can pass to your unborn baby and cause serious health problems (see rubella and pregnancy)

People who have a weak immune system are also more at risk of having complications, such as those with HIV/AIDS or illnesses such as leukaemia. Complications of rubella include:

-

stiff and painful joints – this can occur in six out of 10 women with rubella and is less common in children

-

bleeding problems (thrombocytopaenia) – this can occur in one in 3000 people with rubella and is slightly more common in children

- inflammation of the brain (encephalitis) – this is very rare, it may occur in about one in 6000 people with rubella

Causes of rubella

Rubella infection is caused by a virus which grows in the throat and lungs. The rubella virus spreads from person to person as droplets in the air. Sneezing or coughing produces more droplets and helps to spread the infection.

You will be infectious (able to pass on the rubella virus) for seven days before the rash develops and for four days after.

Once infected, the virus gets into your blood and spreads throughout your body in about five to seven days. This is when the virus can pass from you to your unborn baby.

If a baby is born with rubella, he or she will have congenital rubella syndrome and can pass on the virus to other people for a year or more.

Diagnosis of rubella

If you suspect that you or your child has rubella, phone your GP. Don’t visit your GP without calling them first. If you do, you will put any pregnant women who may be there at risk of catching the rubella infection.

Your GP will examine you and ask about your symptoms. If your GP suspects that you or your child has rubella, by law, he or she has to report it to the Health Protection Unit.

Your GP may do a blood test to confirm diagnosis.

Treatment of rubella

There is no specific treatment for rubella. However, there are things you can do to help yourself feel better.

Self-help

- Drink enough fluids to stop dehydration; this is particularly important in young children.

- Use tissues with menthol or moisturisers to wipe your nose – they may help ease breathing and prevent sore skin.

- Suck sweets or lozenges with menthol or eucalyptus to sooth your throat.

- Eat a balanced diet with plenty of fruit and vegetables.

It’s very important that you stay away from pregnant women for at least five days after the start of the rash. Don’t go back to school or work during this time.

Medicines

For adults, use the painkiller that you would normally take for a headache to help relieve the fever and pain. Children can take liquid painkillers. Before taking any medicines ask your pharmacist for advice and follow the instructions in the patient information leaflet that comes with the medicine.

Rubella and pregnancy

If you’re pregnant

If you have rubella when you’re pregnant, it may lead to complications such as miscarriage or serious birth defects. You baby is very likely to have birth defects if you get the infection in the first trimester of pregnancy. This is known as congenital rubella syndrome.

Birth defects can include:

- deafness

- heart and lung defects

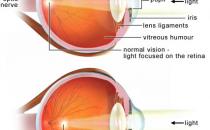

- cataracts (cloudy patches in the lens of the eye) or other eyesight problems

- small head – the brain isn’t fully developed

- low birthweight

Children born with congenital rubella syndrome can develop problems in later life, such as:

- developmental and learning problems

- eyesight and hearing problems

- diabetes

- overactive or underactive thyroid

If you’re planning a pregnancy

If you’re considering having a baby, you should have your immunity to rubella checked before becoming pregnant. Immunity to rubella can wear off over time, so you should have the check even if you have been immunised or had the infection in the past.

Your GP will do a blood test and send it to a laboratory to check for antibodies. If the test shows you have low immunity to rubella, your GP will offer you a vaccine to protect you against rubella. You should not become pregnant for three months after the immunisation.

If you’re already pregnant, the vaccine is given after the delivery of your baby. There’s no treatment to prevent or reduce infection from mother to baby once you’re pregnant.

Prevention of rubella

The most effective way to protect against rubella is immunisation with the MMR vaccine – a combined vaccine against measles, mumps and rubella. This is usually given to children between 12 and 15 months and then between the ages of three-and-a-half and five years. However, the vaccine can be given at any age.

The British Medical Association (BMA), Department of Health (DH), and World Health Organisation (WHO) recommend that all children should have the MMR vaccine. It’s very important that as many people as possible are immune to the virus so that serious health problems are not caused by an outbreak of mumps, measles, or rubella.

In recent years, a claim was made about a link between the MMR vaccine and autism and bowel disease. All subsequent studies show there is no connection between them. However, if you have any concerns about the MMR vaccine, talk to your GP.

Should men have the rubella vaccine?

Should my child stay off school if he or she has rubella?

Why is rubella also called German measles?

Are there serious health risks if my child has the MMR vaccine?

What shall I do if my child has been in contact with confirmed or suspected rubella?

Should men have the rubella vaccine?

Yes, everyone should be given the vaccine.

Explanation

Rubella is as infectious as flu and can easily be passed between people through droplets of infected mucus or saliva in the air (for example, when a person infected with rubella coughs or sneezes). Although it’s a mild illness, rubella can cause serious complications. For example, rubella can harm unborn babies.

Should my child stay off school if he or she has rubella?

Yes, keep your child at home if he or she has rubella.

Explanation

You need to keep your child off school for five days after he or she has developed the rash caused by rubella. This will help to reduce the risk of other children at school getting the virus.

If you’re pregnant, you should be aware that rubella can harm your unborn baby. Before getting pregnant you should check your immunity to rubella. If you are not immune, you can have the vaccine before you get pregnant, but you will need to wait for at least three month before trying for a baby.

Why is rubella also called German measles?

This is because the disease was first diagnosed as an illness, separate from measles, in Germany.

Explanation

Measles and rubella (German measles) infection can be confused but there are differences between the two.

You will generally feel more ill if you have measles compared to rubella, which is much milder. With measles, the rash usually lasts up to a week, but with rubella it clears within four or five days. With measles, you may get small red spots with white centres inside your mouth (called koplik spots), but not with rubella.

Are there serious health risks if my child has the MMR vaccine?

No vaccine is absolutely safe. Some children do have mild side-effects from the MMR vaccine. Serious side-effects are very rare.

Explanation

The side-effects of the vaccine are usually mild and, most importantly, they are milder than the potentially serious consequences of having measles, mumps or rubella.

Around one in 10 children may have a mild fever, rash and swollen glands six to 10 days after the MMR vaccine.

Serious side-effects of the MMR vaccine are very rare and can include the following.

- Fit caused by the fever (febrile convulsion) – this can occur in one in 1000 immunised children. However, one in 200 children with measles may have a febrile convulsion caused by the disease.

- Swelling in the brain (encephalitis) – this is an extremely rare complication of the MMR vaccine. But, the chance of developing encephalitis from measles is between one in 200 and one in 5000.

In recent years, a claim was made about a link between the MMR vaccine and autism and bowel disease. All subsequent studies show there is no connection between them. However, if you have any concerns about the vaccine, talk to your GP.

What shall I do if my child has been in contact with confirmed or suspected rubella?

The most important step is to keep away from pregnant women. If you are pregnant or trying to get pregnant, phone your GP and get medical advice.

Explanation

Rubella generally is a mild illness in children and adults, but it can seriously harm a developing foetus (unborn baby) in the first three months of pregnancy.

If you have been in contact with confirmed or suspected rubella and you don’t have any immunity to rubella (never had the vaccine or the infection previously) then it’s very likely you will develop the illness (rash). Rubella is most contagious in the seven days before and four days after the rash appears. However, it can take two to three weeks before you show any signs of the rash.

If you or your child has been in contact with confirmed or suspected rubella, let your place of work and the school know. If you or your child develops the rash, stay away from pregnant women for at least five days after the start of the rash. Don’t go back to school or work during this time.

Further informa tion

-

Health protection agency

www.hpa.org.uk

Sources

- Rubella. Health Protection Agency. www.hpa.org.uk, accessed 17 February 2010

- Rubella. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. www.cks.library.nhs.uk, accessed 17 February 2010

- Rubella. Department of Health. www.dh.gov.uk, accessed 17 February 2010

- Rubella. World Health Organisation. www.who.int, accessed 17 February 2010

- The delayed effects of CRS. Sense. www.sense.org.uk, accessed 17 February 2010

- Antenatal care – routine care for the healthy pregnant woman. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2008. Clinical Guidelines 62. www.nice.org.uk

- Measles, mumps, rubella: prevention. BMJ Clinical Evidence. www.clinicalevidence.bmj.com, accessed 17 February 2010

- Rubella update: talking sense, 2003. Sense. www.sense.org.uk, accessed 17 February 2010

- Protecting women against rubella: switch from rubella vaccine to MMR, 2003. Department of Health. www.dh.gov.uk

Related topics

- Fever in children

- Measles, mumps and rubella vaccine

- Planning a pregnancy