Ventricular tachycardia

Ventricular tachycardia causes your heart to beat too fast, usually at a rate of about 120 to 200 beats per minute. Ventricular tachycardia is a type of arrhythmia (abnormal heart rhythm) caused by faulty electrical signals in your heart muscle fibres..

The different types of arrhythmia

About ventricular tachycardia

Symptoms of ventricular tachycardia

Complications of ventricular tachycardia

Causes of ventricular tachycardia

Diagnosis of ventricular tachycardia

Treatment of ventricular tachycardia

The different types of arrthythmia

The information on the video provided does not constitute advice on diagnosis or the treatment for heart disease and such advice should always be sought from a doctor or another suitably qualified health professional.

About ventricular tachycardia

Tachycardia means a rapid heart rate, usually of more than 100 beats per minute. Ventricular means that the problem starts in the lower chambers of your heart (the ventricles).

Ventricular tachycardia can be life-threatening, especially if other heart problems already exist, such as heart disease or a history of heart attack. However, ventricular tachycardia can occur with an apparently normal heart. This is usually a less serious condition.

What happens in ventricular tachycardia?

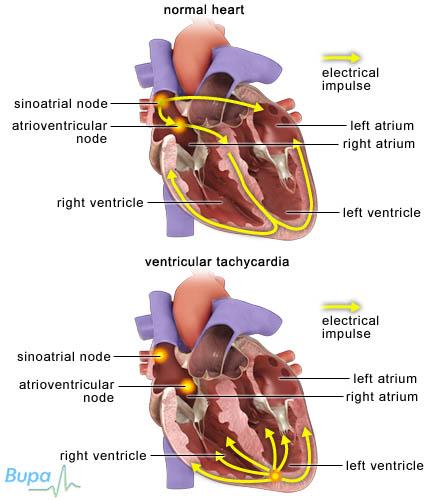

Your heartbeat is controlled by electrical signals (impulses), which start in a part of your heart wall called the sinus node and travel through your heart making it contract. The signals travel from your atria (the upper chambers of your heart) to your ventricles (the lower chambers of your heart) through an area called the atrioventricular (AV) node. The AV node helps to synchronise the pumping action of your atria and ventricles.

Ventricular tachycardia occurs when the electrical signals in your ventricles become disorganised, overriding your heart's normal rate and rhythm. This causes your ventricles to contract faster than normal. Your heart then pumps out blood quicker than normal and your ventricles may not have enough time to fill up properly with blood.

Symptoms of ventricular tachycardia

You will generally feel well in between attacks. Symptoms during an attack of ventricular tachycardia may include:

- palpitations – you're aware of your heart beating faster or more forcefully

- chest pain or discomfort

- shortness of breath

- severe dizziness

- fainting

If you get these symptoms, this is known as ventricular tachycardia with a pulse. There is another form of ventricular tachycardia where the heart stops pumping blood around the body (pulseless ventricular tachycardia). This is an emergency situation.

These symptoms may be caused by problems other than ventricular tachycardia, however, if you have them, seek urgent medical advice.

Complications of ventricular tachycardia

If you have heart disease or have had a heart attack in the past, ventricular tachycardia can lead to a life-threatening condition called ventricular fibrillation, which causes cardiac arrest. Cardiac arrest is when your heart stops pumping blood around your body.

This is life-threatening and usually fatal unless corrected within a minute or two.

Causes of ventricular tachycardia

Many conditions that affect your heart or blood circulation can cause ventricular tachycardia. These include:

- heart valve disease

- heart muscle disease (cardiomyopathy)

- coronary artery disease

- heart problems since birth (congenital heart disease)

Certain factors can trigger ventricular tachycardia, such as:

- certain medicines or illegal drugs

- emotional or physical stress (including exercise)

You may develop ventricular tachycardia without having any apparent underlying cause or risk factor.

Diagnosis of ventricular tachycardia

Ventricular tachycardia is diagnosed with an electrocardiogram (ECG). An ECG is a test that records the electrical activity of your heart. An ECG will be done if you have had a heart attack, have suddenly become unwell with symptoms, such as chest pain and fainting, or if there is anything else to suggest a heart problem.

If you have symptoms, such as palpitations or fainting episodes, a doctor or cardiologist (a doctor that specialises in heart conditions) will ask you about your medical history and may suggest you have an ECG. If your ECG test suggests you have ventricular tachycardia, you will need to go to hospital immediately for the following tests.

- Blood tests.

- Echocardiogram. An ultrasound scan of your heart providing a clear image of your heart muscles and valves that shows how well your heart is working.

- Ambulatory ECG. This takes a recording of your heartbeat while you go about your normal daily activities, over 24 hours or longer.

- Electrophysiological study. This uses electrode catheters to record and stimulate your heart, allowing your doctor to check your heart's electrical activity in greater detail than an ECG.

- Angiogram. A dye visible on X-rays is injected into your coronary arteries to show up any narrowing or blockages.

Please note that availability and use of specific tests may vary from country to country.

Treatment of ventricular tachycardia

Treatment of ventricular tachycardia is aimed at stopping attacks, treating symptoms and preventing future attacks.

Emergency treatment

A ventricular tachycardia attack can sometimes stop by itself. However, if the attack is sustained (lasts for longer than 30 seconds) you may need hospital treatment to stop it.

If your symptoms are not severe, you may be given an antiarrhythmic medicine, such as amiodarone, through a drip in your arm to get your heart rhythm back to normal. This is known as pharmacological cardioversion.

If you're having symptoms, such as low blood pressure, breathlessness, dizziness and chest pain, or are falling unconscious, it means that there may be an immediate risk of your condition getting worse and your heart going into ventricular fibrillation. This can be fatal. You will need to have an emergency procedure called electrical (DC) cardioversion.

In this procedure, a controlled electrical current is applied to your chest via a machine called a defibrillator to help restore your heart to its normal rhythm. You will have a general anaesthetic for DC cardioversion, which means you will be asleep during the procedure.

Medicines

There are several different types of medicine that can help control your heart rate and rhythm, including beta-blockers, calcium-channel blockers and antiarrhythmic medicines.

If your symptoms are not severe, your doctor may prescribe a combination of any of these medicines. You may have to take them for just a short period of time until you have another treatment to restore your heart rhythm, such as DC cardioversion. Alternatively, you may be given medicine to take just when you get symptoms.

Always ask your doctor for advice and read the patient information leaflet that comes with your medicine.

Availability and use of medicines may vary from country to country.

Surgery

Catheter ablation is now a preferred option for many people with ventricular tachycardia. This is when small tubes called electrode catheters are passed into the veins in your groin and threaded up to your heart. Abnormal tissue that is disrupting the electrical signals in your heart is burnt or frozen away.

Implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) treatment

You may need to have an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) fitted to detect ventricular tachycardia and restore your heart to a regular, slower rhythm in the event of future attacks.

An ICD is a device implanted under your skin, usually near your collarbone on your left side. It monitors your heartbeat and when it detects that your heart rate is too fast, it will carry out at least one of three treatments described below.

- Pacing. Your ICD stimulates your heart electrically to correct attacks of ventricular tachycardia. This is known as override pacing.

- DC cardioversion. If ventricular tachycardia continues despite the pacing treatment, your ICD will deliver an internal shock to correct it.

- Defibrillation. If the rhythm problem continues even after the DC cardioversion, the ICD will deliver a larger internal shock, called defibrillation.

Availability and use of different treatments may vary from country to country. Ask your doctor for advice on your treatment options.

Produced by Alice Rossiter, Bupa Health Information Team, August 2012.

Answers to questions about ventricular tachycardia

Can I drive if I have ventricular tachycardia?

Why do I need an ICD if I haven’t had any symptoms of tachycardia?

What is torsades de pointes?

Can I drive if I have ventricular tachycardia?

There are some circumstances in which you may not be allowed to drive. You must follow your doctor’s advice and check with the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA).

Explanation

The DVLA advice states that you must not drive if you have an arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat) that has caused, or is likely to cause incapacity (an inability to drive, for example fainting at the wheel). However, you can drive again if an underlying cause for your arrhythmia has been identified and it has been controlled for at least four weeks.

If you have catheter ablation, depending on your individual circumstances, you won’t be allowed to drive for two to six weeks after the procedure; discuss this with your doctor.

If you have an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD), depending on your individual circumstances, you may not be allowed to drive for six months after having the ICD fitted. In some cases, this period may be extended.

Why do I need an ICD if I haven’t had any symptoms of tachycardia?

Implantable ICDs can be used in people who are thought to be at high risk of ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation, even if they haven’t had any symptoms yet. The devices act as a safeguard by giving you immediate treatment in case you have an attack.

Explanation

An ICD is a device that can monitor your heart rhythm and return your heart beat to normal if you have an attack of ventricular tachycardia.

Prompt treatment for ventricular tachycardia, and especially ventricular fibrillation, can be very important – as without it, your heart may stop beating altogether (cardiac arrest). If you’re thought to be at high risk for ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation, your doctor may suggest you have an ICD fitted; this ensures that if you ever have an attack, the device can provide you with immediate treatment.

You may be at high risk if you have:

• previously had a heart attack

• disease of the heart muscle

• an inherited condition of the heart

Not everyone who has one of these conditions will need an ICD. Your doctor will talk to you before you have the procedure to make sure you understand the risks, benefits and possible alternatives.

What is torsades de pointes?

Torsades de pointes is a form of ventricular tachycardia. It occurs typically in people who have a condition called a long QT syndrome.

Explanation

Your heartbeat is controlled by electrical signals (impulses). In long QT syndrome the time it takes for the heart to recharge after each heartbeat is longer than normal.

There are several factors that can also cause long QT syndrome:

• an inherited condition of the heart

• certain anti-arrhythmic medicines or antidepressants

• lack of calcium or magnesium

• poisoning with insecticides or heavy metals

If you have long QT syndrome, you’re more likely to get torsades de pointes. Episodes of torsades de pointes can be triggered by stress, physical exercise or when something makes you jump – such as an alarm going off. It often stops by itself, but can sometimes lead to ventricular fibrillation, which is very dangerous as it can cause your heart to stop beating altogether (cardiac arrest).

Treatment for torsades de pointes depends on what is causing your condition and includes the following options.

• Medicines called beta-blockers.

• A pacemaker implanted to regulate your heartbeat.

• A cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) if you have a family history of sudden death. This is a device, similar to a pacemaker, that is implanted near your collarbone. It can monitor your heart rhythm and return your heartbeat to normal when you have an attack of ventricular tachycardia.

Keywords: heart, arrhythmia, ventricular, irregular heartbeat, pacemaker

Further information

• Arrhythmia Alliance

01789 450787

www.heartrhythmcharity.org.uk

• The British Heart Foundation

0300 330 3311

www.bhf.org.uk

Sources

- Simon C, Everitt H, Kendrick T. Oxford handbook of general practice. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010: 276–77

- Camm A, Luscher T, Serruys PW. The ESC textbook of cardiovascular medicine. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009

- Assessment of tachycardia urgent considerations. BMJ Best Practice. www.bestpractice.bmj.com, published 26 September 2011

- Heart rhythms. British Heart Foundation. www.bhf.org.uk, published May 2009

- Palpitations – management. Prodigy. www.prodigy.clarity.co.uk, published March 2009

- Assessment of tachycardia aetiology. BMJ Best Practice. www.bestpractice.bmj.com, published 26 September 2011

- Tachycardia. American Heart Association. www.heart.org, published 5 April 2012

- Cardiac arrest. British Heart foundation. www.bhf.org.uk, accessed 4 July

- Implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs). British Heart Foundation. www.bhf.org.uk, published January 2010

- Ventricular tachycardia etiology. eMedicine. www.emedicine.medscape.com, published 9 November 2011

- Assessment of tachycardia step-by-step diagnostic approach. BMJ Best Practice. www.bestpractice.bmj.com, published 26 September 2011

- Synchronized electrical cardioversion. eMedicine. www.emedicine.medscape.com, published 9 May 2011

- Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary. 62nd ed. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain; 2011

- Catheter ablation. Arrhythmia Alliance. www.arrhythmiaalliance.org.uk, published April 2010

- Information for medical professionals. Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA). www.dft.gov.uk, published April 2012

- Drew BJ, Ackerman MJ, Funk M, et al. Prevention of torsade de pointes in hospital settings. Circulation 2010;121: 1047–60

- What is long QT syndrome? National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. www.nhlbi.nih.gov, September 2011

- Torsade de Pointes. eMedicine. www.emedicine.medscape.com, March 2011

- Ventricular Tachycardia (VT). The Merck Manuals. www.merckmanuals.com, published January 2008

Related topics

• Arrhythmia

• Cardiovascular system

• Cardioversion

• Electrocardiogram (ECG)