Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Published by Bupa's Health Information Team, October 2011.

This factsheet is for people who have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or who would like information about it.

COPD describes a number of long-term lung conditions that cause breathing difficulties.

About COPD

Symptoms of COPD

Causes of COPD

Diagnosis of COPD

Treatment of COPD

Prevention of COPD

About COPD

It’s estimated that 64 million people are affected by COPD worldwide and it’s more common as you get older. COPD is a life-threatening lung disease that tends to get progressively worse and is most commonly caused by smoking.

A chronic illness is one that lasts a long time, sometimes for the rest of the affected person’s life. When describing an illness, the term ‘chronic’ refers to how long a person has it, not to how serious a condition is.

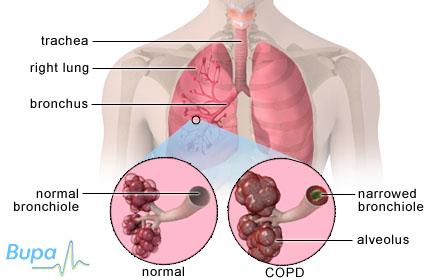

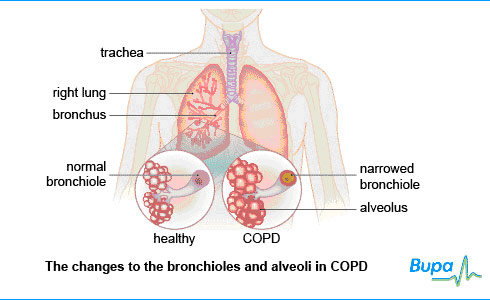

The term COPD has replaced the previously separate conditions of chronic bronchitis and emphysema.

- Chronic bronchitis is inflammation of your bronchi – the main airways that lead from your windpipe (trachea) to your lungs. This inflammation can produce excess mucus that may block your airways and make you cough.

- Emphysema damages the structure of your alveoli – these are tiny air sacs where oxygen passes into your blood. When the alveoli lose their elasticity this reduces the support of the airways, causing them to narrow.

The effects of COPD mean less oxygen passes into your blood.

Symptoms of COPD

At first, you may not notice any symptoms of COPD. The condition progresses gradually, starting with either a ‘phlegmy’ cough or breathlessness. Many people don’t see a doctor at this early stage, but the earlier you get advice and treatment the better.

As COPD progresses symptoms can vary but may also include:

- chronic cough

- breathlessness with physical exertion

- regularly coughing up phlegm

- weight loss

- tiredness and fatigue

- waking up at night as a result of breathlessness

- swollen ankles

You may find your symptoms are worse in the winter months.

It’s rare to get chest pains or cough up blood if you have COPD – if this happens, you may either have a different disease or another disease as well as COPD.

These symptoms aren’t always caused by COPD but if you have them, see a doctor.

Causes of COPD

The biggest single cause of COPD is smoking. If you stop smoking, your chances of developing COPD begin to fall. If you already have COPD, stopping smoking can lead to an improvement of your symptoms and mean it progresses more slowly.

You’re also more likely to get COPD:

- if your job exposes you to certain dusts or fumes

- from environmental factors, such as air pollution

- from inherited problems – an inherited shortage of a protein called alpha antitrypsin that helps protect your lungs from the effects of smoking may increase your risk, but less than one in 100 people with COPD have this

- if you have a weakened immune system, for example HIV/AIDS

Diagnosis of COPD

Your doctor will ask about your symptoms and examine you. He or she may also ask you about your medical history. If your doctor thinks you have COPD, he or she will ask you about the problems you have with your chest and how long you have had them. He or she will usually examine your chest with a stethoscope, listening for noises such as wheezing and crackles.

Your doctor may ask you to perform a lung test called a spirometry test. He or she will ask you to blow into a device that measures how much and how fast you can force air out from your lungs. Different lung problems produce different results so this helps to separate COPD from other chest conditions, such as asthma.

Other tests you may have are listed below.

- A chest X-ray to see if your lungs show signs of COPD, and to exclude other lung diseases.

- A blood test to look for anaemia or signs of infection.

- A CT (computed tomography) scan to produce a three-dimensional image of your lungs.

- An ECG (electrocardiogram) to measure the electrical impulses from your heart to check if you have heart and/or lung disease.

- An echocardiogram to see how well your heart is working.

- A pulse oximeter to monitor the amount of oxygen in your blood to see if you need oxygen therapy.

- An antitrypsin deficiency test – you may need this if your COPD developed when you were 40 or younger, or if you don’t smoke.

Please note that availability and use of specific tests may vary from country to country.

Treatment of COPD

There isn’t a cure or a way to reverse the damage to your lungs, but there are things you can do to stop COPD from getting worse. The most important treatment is to stop smoking. Giving up smoking can relieve your symptoms and slow down the progression of COPD, even if you have had it for a long time. Speak to your doctor about ways to give up smoking.

Self-help

There are other steps you can take to stop COPD getting worse and to ease your symptoms. Some examples are listed below.

- Keep up your fluid levels by making sure you drink enough water and use steam or a humidifier to help keep your airways moist – this can help to reduce the thickness of mucus and phlegm that are produced.

- Exercise to keep moving and eat a healthy diet to help your heart and lungs.

- Have a flu vaccination each year, as COPD makes you particularly vulnerable to the complications of flu, such as pneumonia (bacterial infection of the lungs).

- Have a vaccination for the Streptococcus pneumoniae bacterium that causes pneumonia.

Pulmonary rehabilitation

Ask your doctor about pulmonary rehabilitation. These are programmes consisting of exercise, education about COPD, advice on nutrition and psychological support. They aim to help reduce your symptoms and make it easier for you to do everyday activities.

Medicines

There are various medicines that may help to ease your symptoms or control flare-ups. Discuss with your doctor which medicine is best for you.

Bronchodilators

These medicines are commonly used for asthma and COPD. They widen your airways so air flows through them more easily and relieve wheezing and breathlessness. They are available as short-acting or long-acting inhalers or tablets.

Steroids

Steroid treatments may help if you have more severe COPD. Steroids work by reducing inflammation of the airways. They are available as inhalers or tablets.

You may be prescribed a short course of tablets for one or two weeks when you have a flare-up, or some people may be given a steroid inhaler to take regularly.

Mucolytics

Mucolytics break down the phlegm and mucus produced, making it easier for you to cough it up. Your doctor may prescribe you a mucolytic if you have a chronic phlegm-producing cough.

Oxygen therapy

If your COPD becomes severe, you may develop low blood oxygen levels. Oxygen therapy can help relieve this. You inhale oxygen through a mask or small tubes (nasal cannulae) that sit beneath your nostrils.

The oxygen is provided in large tanks for home use or in smaller, portable versions for outside the home. An oxygen concentrator – a machine that uses air to produce a supply of oxygen-rich gas – is an alternative to tanks.

It’s particularly important to give up smoking if you have oxygen therapy for COPD because there is a serious fire risk. Oxygen therapy can either be short-term, long-term (when

Surgery

If you have severe COPD, your doctor may recommend surgery to remove diseased areas of your lungs. This can help your lungs to function better. However, it’s only carried out in certain circumstances – speak to your doctor for more advice.

Availability and use of different treatments may vary from country to country. Ask your doctor for advice on your treatment options.

Prevention of COPD

You have the best chance of preventing COPD if you don’t smoke.

If your job exposes you to dust or fumes, it’s important to take care at work and use any relevant protective equipment, such as face masks, to help prevent you from inhaling any harmful substances.

This section contains answers to common questions about this topic. Questions have been suggested by health professionals, website feedback and requests via email.

Should I exercise if I have COPD?

Why is diet important for people with COPD?

Is there anything I can do to help when I feel breathless?

What do the results of my spirometry test mean?

Should I exercise if I have COPD?

Answer

It’s important to try to do as much exercise as you can if you have COPD, even if it makes you feel a little out of breath.

Explanation

If you have COPD, you may feel as if you don't want to do anything that will make you get even more out of breath. Many people with COPD reduce how much activity they do because they worry that getting breathless can be dangerous. However, this isn't true. In fact, reducing the amount of activity you do can make things worse, as this will decrease your fitness and you will become breathless more quickly when you’re active.

Taking regular, light exercise and gradually building up the amount you do can help to improve your breathing and make you feel better. It's safe to become a little short of breath, but don't overstrain yourself.

Try to adapt your lifestyle to keep as active as possible. If you're able to walk, try to walk for 20 to 30 minutes, three to four times a week. Try taking short walks, even if it's just around the house or up and down the garden. Don't worry if you get a little breathless, just take a break to get your breath back then start again. If you can’t walk, your GP or the physiotherapist can teach you exercises to do at home to help clear mucus. These are likely to involve upper body exercises, such as twisting and arm stretches.

Ask your GP if there are any pulmonary rehabilitation schemes in your area that he or she can refer you to.

It's worth trying to keep as active as possible, as even a small amount of exercise can help if you have severe lung problems.

Further information

British Lung Foundation

0845 850 5020

www.lunguk.org

Sources

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. www.cks.library.nhs.uk, accessed 10 June 2009

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2004. www.nice.org.uk

- Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease, 2008. www.goldcopd.com

- Exercise and the lungs. British Lung Foundation. www.lunguk.org, accessed 10 June 2009

Why is diet important for people with COPD?

Answer

It's important to eat a healthy diet and maintain a healthy weight to help your heart and lungs. It's common to lose weight if you have COPD. Being underweight can make you feel weak and make it harder to fight off infections. On the other hand, if you’re overweight, this means your heart and lungs have to work harder to supply oxygen to your body, making it harder to breathe.

Explanation

If you have COPD you’re likely to lose weight. There can be a number of reasons for this including:

- using up a lot of the energy you get from food with the increased effort of breathing

- not feeling like eating much if you feel breathless

- absorbing less nutrients than usual from your food

Being underweight can make you feel weak and tired, and put you at greater risk of chest infections. Therefore, it's more important than ever to maintain a healthy weight if you have COPD. The following tips can help if you're finding it hard to eat enough food.

- Eat little and often so you don’t get breathless and to reduce the feeling of bloatedness.

- Choose food that is high in protein such as meat, fish and dairy products, but try not to eat sugary foods and foods that are high in fat.

- If you have lost your appetite, try to vary the types of food you eat or have a high energy drink if you find it hard to eat anything.

- When cooking, make more food than you need and freeze the extra so you have a meal ready for days when you don't feel like cooking.

- Take advantage of meals offered by community centres, clubs or churches.

- Drink plenty of water, unless advised not to by your GP. This will help to keep the lining of your airways moist and the mucus thinner.

If you're very underweight, your GP may give you nutritional supplements to help bring you back up to a healthy weight. Ask your GP for advice if you're unsure about your weight.

If you're overweight, try to eat smaller portions and increase the amount of exercise you do. It may not be good for you to lose weight too quickly so ask your GP or dietitian for advice.

Further information

British Lung Foundation

0845 850 5020

www.lunguk.org

Sources

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. www.cks.library.nhs.uk, accessed 10 June 2009

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2004. www.nice.org.uk

- Healthy eating and your lungs. British Lung Foundation. www.lunguk.org, accessed 10 June 2009

- COPD: living with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). British Lung Foundation. www.lunguk.org, accessed 10 June 2009

Is there anything I can do to help when I feel breathless?

Answer

Yes. There are various breathing techniques that can help you to cope if you get short of breath suddenly.

Explanation

If you get short of breath, the key thing is to try to relax and keep calm. Find a comfortable, supported position where you can relax your shoulders, arms and hands. This may mean sitting down, or finding something you can lean against and that will support you, such as a chair, wall or windowsill.

Focus on breathing in gently through your nose and out through your nose or mouth.

If you find you get out of breath when you're more active, try the following techniques.

- Focus on taking deep, slow breaths – in through your nose and out through your mouth.

- Purse your lips (as if you're whistling) – this slows your breathing down and helps to make your breathing more efficient.

- Breathe out whenever you do something that takes a lot of effort, such as going up a stair or step, bending down, standing up or reaching for something.

- Adjust your breathing so it's in time with whatever activity you're doing (for example, going up the stairs or walking). For instance, breathe in when you're on a stair and out as you step up to the next one.

A physiotherapist can teach you more about breathing control and exercises.

Further information

British Lung Foundation

0845 850 5020

www.lunguk.org

Sources

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2004. www.nice.org.uk

- COPD: Living with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). British Lung Foundation. www.lunguk.org, accessed 10 June 2009

What do the results of my spirometry test mean?

Answer

Your GP will measure how much air you can blow out in one breath, and also how quickly you blow it out. This will help to find out if you have COPD or any other breathing problems.

Explanation

The measurements that your GP takes during the spirometry test are called the forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and the forced vital capacity (FVC).

- The FEV1 is the amount of air you can blow out in one second.

- The FVC is the total amount of air that you can blow out in one breath.

Your GP will use these measurements to work out the proportion of your total breath that you can blow out in one second. This is the FEV1 divided by FVC (FEV1/FVC).

The three measurements can help your GP to find out whether you have COPD or any other breathing problems. He or she will compare the values you get with those that would be expected for someone of your age, height and sex.

If you have COPD, you won’t be able to blow air out as quickly as someone who doesn't have the disease. This means that your:

- FEV1 will be lower than normal (below 80 percent of what would be expected) as you can’t blow out as much air in one second

- FEV1/FVC will be low (below 0.7, when the highest number you can have is 1) as you can only breathe out a small proportion of the total amount of air in your lungs in one second

The smaller your values for FEV1 and FEV1/FVC, the more severe your COPD is likely to be. If you have any questions about your spirometry test results, ask your GP to explain what they mean.

Further information

British Lung Foundation

0845 850 5020

www.lunguk.org

Sources

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2004. www.nice.org.uk

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. www.cks.library.nhs.uk, accessed 10 June 2009

Related topics

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Asthma in adults

Healthy weight for adults

Healthy eating

Physical activity

This information was published by Bupa's health information team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been peer reviewed by Bupa doctors. The content is intended for general information only and does not replace the need for personal advice from a qualified health professional.

Publication date: October 2009.

Related topics

Anaemia

Asthma in adults

Flu and colds

Giving up smoking

Further information

- World Health Organization

www.who.int

- European Lung Foundation

www.european-lung-foundation.org

Sources

- Your lungs. British Lung Foundation. www.lunguk.org, published August 2007

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. World Health Organization. www.who.int, published November 2011

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: management of chronic obstructive disease in adults in primary and secondary care. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), June 2010. www.nice.org.uk

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. World Health Organization. www.who.int, published November 2011

- COPD. BMJ Clinical Evidence. www.clinicalevidence.bmj.com, published 6 June 2011

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. eMedicine. www.emedicine.medscape.com, published 12 July 2011

- Simon C, Everitt H, van Dorp F. Oxford handbook of general practice. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010:322–27

- COPD. European Lung Foundation. www.european-lung-foundation.org, accessed July 2011

- COPD. BMJ Best Practice. www.bestpractice.bmj.com, published 22 June 2010

- Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary. 61st ed. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain; 2011

- Top tips for a healthy workforce. Health and Safety Executive. www.hse.gov.uk, accessed 25 July 2011

- Home exercises for COPD. The Asthma Foundation. www.asthmafoundation.org.nz, accessed 20 July 2011

- Spirometry in practice. British Thoracic Society. www.brit-thoracic.org.uk, published April 2005

- What is the difference between asthma and COPD? Department for Work and Pensions. www.dwp.gov.uk, accessed 25 July 2011

This information was published by Bupa’s health information team and is based on reputable sources of medical evidence. It has been peer reviewed by Bupa doctors. The content is intended for general information only and does not replace the need for personal advice from a qualified health professional.